As Oscars night draws near, I ask what makes a film truly great and remember a few films that had the most profound, life-changing impact on me

In a few days – commencing Sunday 2 March at 4pm (PCT) – the Academy of Motion Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) will present the 97th Academy Awards (aka, the Oscars) ceremony at the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood. With such a wealth of stellar acting, dynamic, original, evocative and beautifully produced films, tensions are running high as predictions of the top winners chop and change daily.

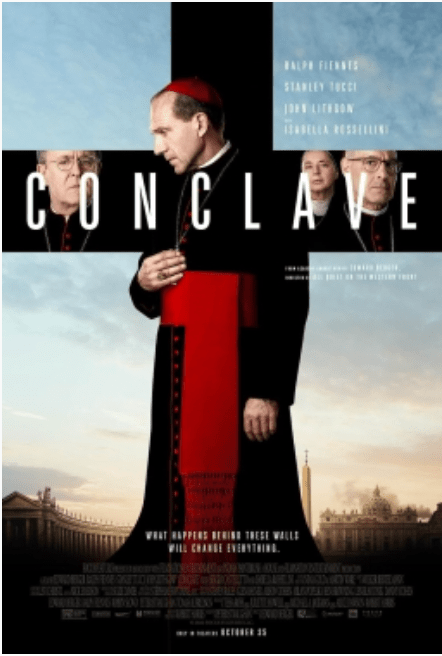

Considering all the heated hypes and gripes the annual Academy Awards season usually brings, you’d be forgiven for thinking cinema’s real power lies in the political dramas lurking behind the scenes — rather like the conniving cardinals in taut papal thriller ‘Conclave’. Indeed, over the Oscars’ 97 years, these have often overruled common sense, the most well-argued and logically deduced bettors’ odds, and even skyrocketing box-office stats (see Adam White’s article on the reasoning behind some bewildering recent choices and Donald Clarke’s far-from-exhaustive list of historical Oscar upsets).

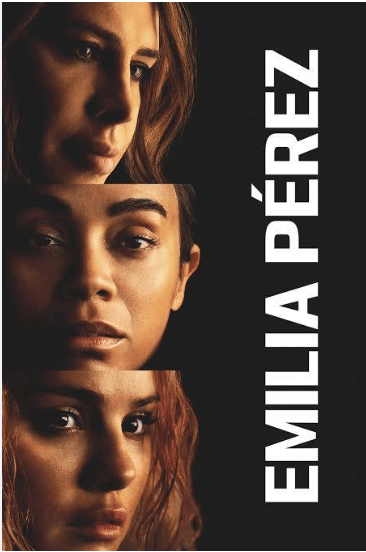

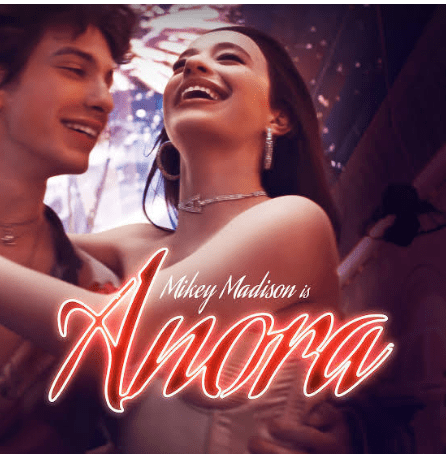

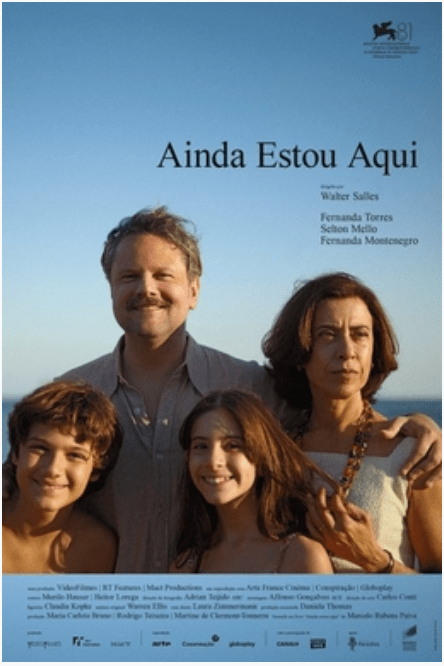

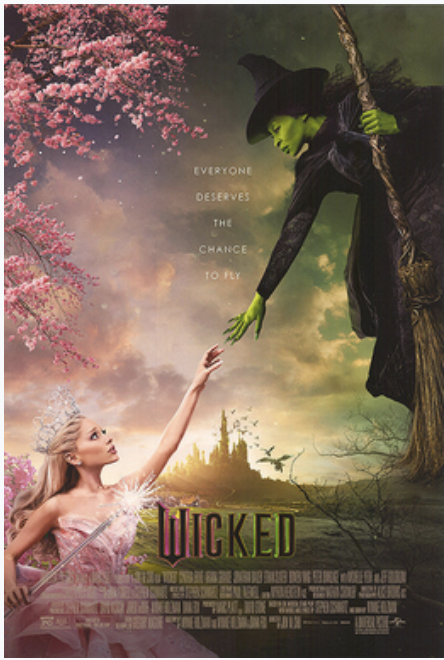

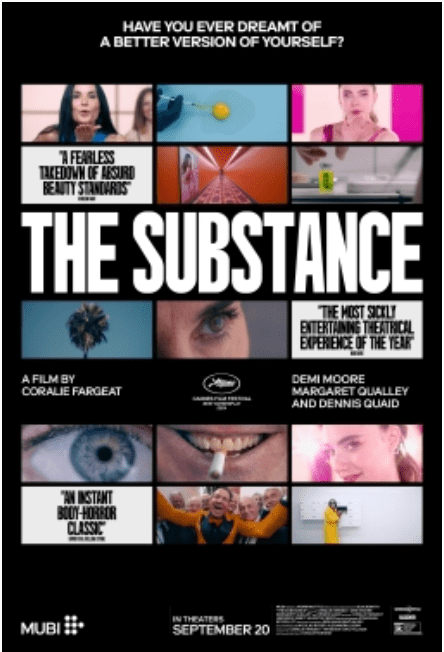

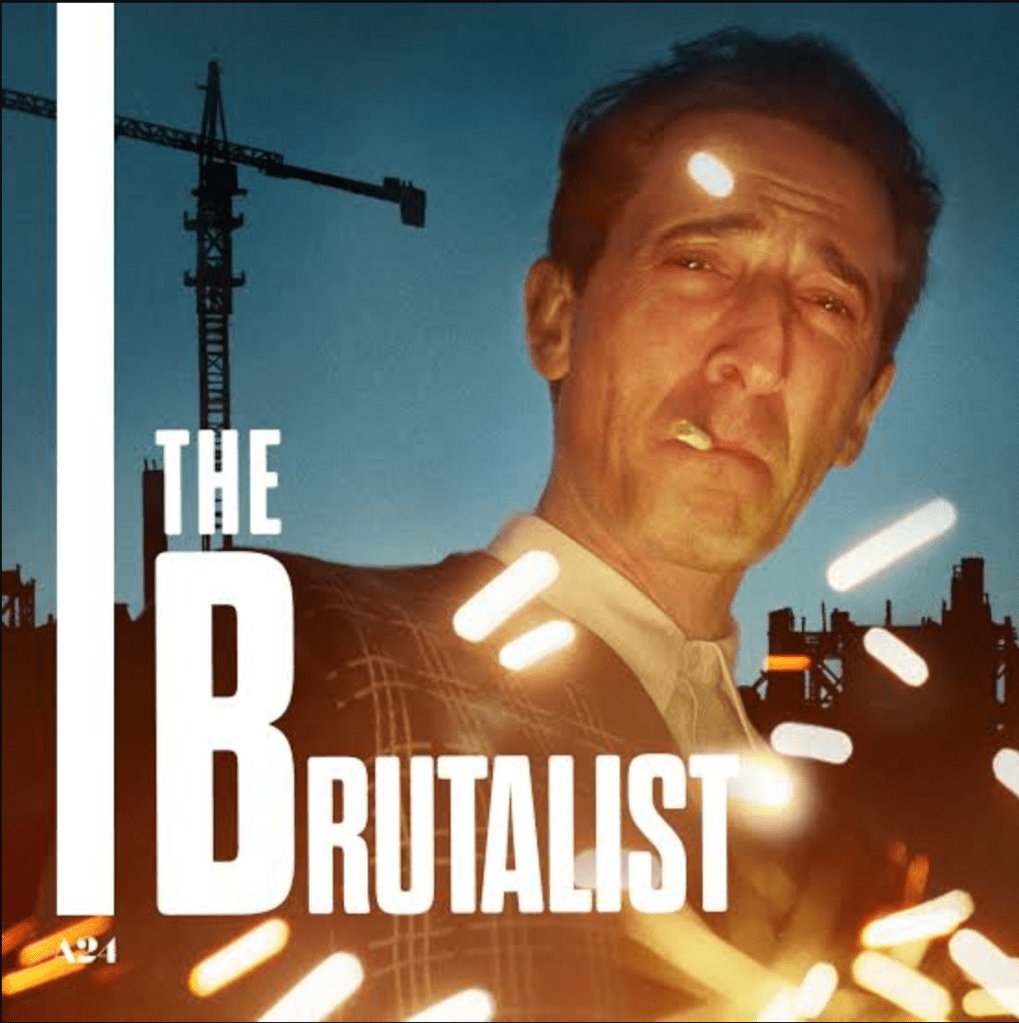

This year’s Oscar race is no exception, with former front-runners ‘The Brutalist’ and ‘Emilia Pérez’ currently bogged down in racist and AI controversies, and rival awards (Critics’ Choice, Screen Actors’ Guild, Golden Globes, BAFTAs, etc) now tilting the scales in favour of ‘Anora’, ‘Conclave’, ‘A Complete Unknown’ or possibly ‘Wicked’. Even body-horror film ‘The Substance’ or moving Brazilian abduction saga ‘I’m Still Here’ stand a decent outside chance (the latter, also up for Best International Film, could easily win that award, particularly as the idea of a French team receiving the prize for Mexican-centred ‘Emilia Peréz‘ is just plain awkward on many levels).

Of course, there could, as always, be several last-minute curveballs swerving in the direction of ‘harrowing, transcendent’ ‘Nickel Boys’, based on Colson Whitehead’s 2020 Pulitzer prize-winning novel, or perhaps visually spectacular sci-fi space opera ‘Dune Part Two’. And that’s just the Best Picture category.

When we get to the Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actor and Best Supporting Actress nominations, it is even tougher to call. While Adrien Brody’s performance as Holocaust-tortured architectural genius László Tóth is as undeniably monumental as Ralph Fiennes’ conflicted cardinal is devoutly nuanced, it is hard to fault the impressive dedication of all three principals in the Bob Dylan biopic, who not only sang, performed and convincingly portrayed real-life musical icons (Timotheé Chalamet as the enigmatic Dylan, Monica Barbaro as a steely-sweet and sexy Joan Baez, and a genius turn by Edward Norton as 60s folk legend Pete Seeger), but seamlessly evoked the zeitgeist of that epic ‘times-they-are-a-changin’ generation.

Before her nosedive into notoriety, Karla Sofia Gascón seemed a shoo-in for best actress; now the battle is seemingly between established actress Demi Moore (‘The Substance’) and newcomer Mikey Madsen (‘Anora’). Yet the Academy could still surprise us by choosing Fernanda Torres’ raw, emotive performance in ‘I’m Still Here’ or Cynthia Erivo’s queen of green in ‘Wicked’ (although her 2019 portrayal of Harriet Tubman was far more deserving). I haven’t seen ‘A Real Pain’, but most pundits consider Kieran Culkin’s Best Supporting Actor win a done deal (even if to my mind Norton really should win for his work in ‘A Complete Unknown’). If Emilia Peréz has any winners now, it will likely be Zoe Saldaña taking home the Best Supporting Actress role. Likewise, most believe ‘Anora’s Sean Baker will win either Best Director or Best Original Screenplay, if not both.

What makes a film truly great is ultimately the power of its story and the deftness with which that story is articulated by the actors, directors and all the other contributing elements combined

As for all the other categories — Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Animated Feature, Best Animated Short Film, Best Live Action Film, Best Documentary Feature Film, Best Documentary Short Film, Best Film Editing, Best Costume Design, Best Makeup and Hairstyling, Best Original Score, Best Cinematography, Best International Feature Film, Best Original Song, Best Production Design, Best Sound and Best Visual Effects — while there are a few variant entries (most notably Latvian nominee ‘Flow’, the ultimate ‘Save the Cat’ film, up for both Best Animated Feature and Best International Feature Film), however, the 10 Best Picture nominees still dominate, leaving ample room for each to still get a golden gong in some category. Or not, as may well be.

So what constitutes a great film?

Although I’ve so far only seen five of the films nominated for this year’s Best Picture award, watching these has prompted me to ponder what it is that makes a film truly Oscar-worthy — or at least nomination-worthy — and whether these are destined to become classics or swiftly forgotten. Alas, too many films ride into Oscar glory simply because they conveniently capture some transient flash-in-the-pan topical issue or simply stun audiences with their sheer, audaciously overwhelming oddity — for example, 95th Academy Award-winner ‘Everything Everywhere All At Once’ springs to mind.

While most big-screen movies offer only a few hours of momentarily rhapsodic but ultimately time-wasting escapism, there are some rare films that make you see the world differently, changing you in both subtle and profound ways that linger long past the end credits

While most of the big-screen movies that have been produced over the past century offer only a few hours of momentarily rhapsodic but ultimately time-wasting escapism, there are some rare films that make you see the world differently, changing you in both subtle and profound ways that linger long past the end credits. Often, it’s the lush cinematography, the sweeping musical score, the lavish sets and costumes, the period details or the sharp editing which, combined with the acting and direction, give winning films a certain je ne sais quoi; it is for good reason these other Oscar categories exist.

A powerful musical score, jaw-dropping cinematography or dazzling special effects can make a film stand out among the nominees, but what makes a film truly great is ultimately the power of its story and the deftness with which that story is articulated by the actors, directors and all the other contributing elements combined. Everything in the film — from the sound to the editing to the locations and set designs — must serve to amplify the central narrative; it must neither intrude nor distract from the story.

To my mind, the goal of a truly good film — and the time test of what makes a great or even a classic one — is that it brings the story to life in such a singularly vivid way that individual scenes, characters, soundtracks and memorable lines stay with you forever, becoming an integral part of your inner cultural landscape. To me, what defines a film classic is, like with a literary classic, that it is one whose story is so deeply immersive and expertly executed that you are drawn to return to it time and time again to relive its enveloping magic, and can always take away something new from repeat viewings.

The goal of a truly good film — and the time test of what makes a great or even a classic one — is that it brings the story to life in such a singularly vivid way that individual scenes, characters, soundtracks and memorable lines stay with you forever, becoming an integral part of your inner cultural landscape

Some film adaptations of novels alter the story for brevity or dramatic effect — such as the woefully underrated and surprisingly un-nominated 2024 film of the Alexandre Dumas classic, ’The Count of Monte Cristo’, which would certainly have been on my Best Picture list — or are disappointingly second-rate versions of the book. Other films, such as the 1939 Hollywood retelling of Margaret Mitchell’s US Civil War novel Gone With the Wind (see below for discussion of the film) may surpass the novel in terms of enduring popularity; even if modern ‘woke’ sensibilities may dissuade people from watching it, Clark Gable’s famous parting words, ‘Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn’ will undoubtedly live on forever. And although Jane Austen fans would still read her books regardless of any silver screen appeal, let’s just say the shirtless Colin Firth as Mr Darcy in the BBC version of Pride and Prejudice hasn’t hurt its popularity.

I confess when it comes to film adaptations of literary works, I sometimes find it easier to watch the film than read the actual novel. Yet if the film has done the book any justice — or perhaps even more so if hasn’t — it often succeeds in whetting my appetite to read the novel and see how well it has been rendered on film by comparison, as it did with the 2012 Keira Knightley version of Tolstoy’s classic Anna Karenina. I also admit to frequently spending ages either Googling the source material — often on a fact-finding mission if any anachronisms jar — or reading alternate reviews, particularly when the ending is ambiguous, as with ‘The Brutalist’. If I read too many contradictory reviews, I feel compelled to see the film to reach my own verdict. I am grateful to ‘A Complete Unknown’ for making me listen to and read the lyrics of countless Dylan songs; I now have a much greater admiration for and interest in his music.

Cinema: A life-long love affair

Having been an avid film fan most of my life, I’ve watched thousands, if not millions, of films — from the earliest black-and-white silent-era movies to glorious technicolour spectaculars to Hollywood classics to musicals to foreign and ‘arthouse’ films to low-budget indie films to documentaries to big-screen literary adaptations, and more. These have also included virtually every genre — sci-fi, fantasy, Western, crime, suspense/thrillers, action/adventure, romance, biopics, comedies/rom-coms and even horror. Although I don’t really do horror — let’s face it, real life is frightening enough — I still get chills though when I think of Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 classic suspense/grief drama ‘Don’t Look Now’. I suppose that makes me a true cinephile, perhaps nearly as earnestly nostalgic about it as the lead character in Guiseppe Tornatore’s 1988 heartfelt homage to cinema, ‘Cinema Paradiso’.

Like the child in that film, I spent hours as a child glued to televised black-and-white film classics, consuming endless romantic melodramas, action-adventure and suspense films. I had a special love for foot-tapping extravaganzas showcasing the legendary hoofing talents of stars like Jimmy Cagney, Eleanor Powell, Fred and Ginger, Gene Kelly, Cyd Charisse and Rita Hayworth, and credit this early obsession with fostering my love for dance and so-called ‘natural dancer’ abilities.

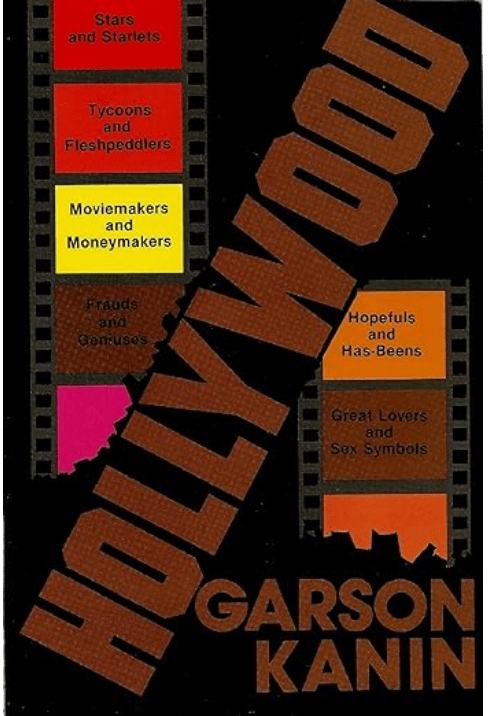

I also collected and devoured classic books on film like Daniel Blum’s A Pictorial History of the Talkies, Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By and Garson Kanin’s Hollywood, and read and studied most of James Agee’s essays on film. I quite possibly would have been a film critic in an alternate life path, but that is another of those ‘ones that got away’ — which is one reason I’m writing this now. We all have our own stories about the things that have most shape and influence us; these are merely my own.

Five of my most memorable, life-changing films, and why

My life-long, obsessive interest in film has changed, charged, inspired and informed me. It has helped form my tastes, views and values in many of the same ways my mutual passions for art and literature have done. Being both a writer and a lover of story as well as a visual artist and lover of image, it is natural I would be drawn to a medium that excels in delivering both at experiential, deeply immersive levels.

Being that I would also class myself an echt ‘romantic’ by nature — I have certainly ascribed to all seven definitions of romanticism defined by CS Lewis in his preface to The Pilgrim’s Regress at some point in my life (see here for a discussion of this) — almost all the films I am most drawn to or influenced by are ‘romantic’ in at least one of these ways. This is not to say that what most people would consider ‘romantic’ in film — eg, films filed under ‘romance’ as a genre — aren’t also worthy or deeply appealing, but the films on my list are mostly ‘romantic’ in the sense of presenting a romantic view of nature, of the past, of exotic, foreign worlds, of adventure, of grand or failed causes, or of some deeper transformation, perhaps something that echoes that sublime and elusive ‘joy’ Lewis spoke of, which we all either knowingly or unknowingly yearn for.

In fact, I would argue that as a medium, film is in itself inherently ‘romantic’, in that it seeks to be transcendent — and when it is done well, it has the ability to stimulate the kind of intense longing and desire Lewis describes. While a good film — say, a comedy, a romance, a brilliant suspense drama or action-adventure movie — can be deeply satisfying on many levels, the best films evoke a deep sense of longing and desire for something ‘other’ — for instance, a perfect romance or a world where justice and truth prevail, or heroic exploits whisper of eternity (I think particularly of the closing song and vision of Russell Crowe’s dying warrior in ‘Gladiator’, to me the most stirring part of that film, and the bit that makes it both a true classic and infinitely re-watchable).

So, here is my rather eclectic list of the top five films that have — and are perhaps still having — a lasting impact on my life, along with the reasons why I have included them here. They are in order of impact, as well as chronological viewing. Where possible, I have included a YouTube link to either a clip, trailer or the full film. As most of these films I watched in my more impressionable childhood and teenage/young adult years, they are of course much older and perhaps forgotten or unknown films, but that’s one reason I wished to share them. I will also include briefer mentions of other films — including a few more recent ones — that have also impacted me significantly or I consider truly great for other reasons.

5. ‘Le Sang d’un Poete’ (The Blood of a Poet), 1932, Jean Cocteau, starring Enrique Riveros and Lee Miller and ‘La Belle et la Bete’ (Beauty and the Beast), 1942, Jean Cocteau, starring Jean Marais and Josette Day

Above, left: Le Sang d’un Poete (1932) and La Belle et la Bete (1942), both Jean Cocteau

I suppose I have cheated a little by including two Jean Cocteau films under the same number, yet both make use of surrealist symbolism in uniquely romantic ways. Despite the fact colour films were already in production by the time of the second film, it was also shot in black and white, to mesmerising effect; although only the first film is silent, the second’s choice of black and white only heightens its sense of magic.

Told in four parts, ‘Le Sang d’un Poete’ simulates the poet’s rich inner, imaginative life and subconscious influences during his symbolic journeys through a mirror into other worlds. I don’t think there is anything that more truly — and poetically — conveys the inner life of a poet. Likewise, Cocteau’s marvellously soulful and truly enchanting version of the ‘Beauty and the Beast’ fairytale is streets ahead of both the Disney 2017 version with Emma Watson and Dan Stevens and the 1991 cartoon version, which in fact borrowed significantly from this earlier classic.

While most people would likely cite Luis Buñuel’s ‘Un Chien Andalou’ (1929) or ‘L’Age d’Or’ (1930) as the ultimate surrealist classics, for me, these two Cocteau films do more than shock; their languid beauty seduces you to enter their lucid dream-like world and compels you to become a co-creator/imaginer — the kind of deeply immersive, intoxicating experience that is infinitely inspiring to artists, poets, storytellers and dreamers everywhere. Beyond that, seeing these films opened my mind to other French avant-garde artistic developments, preserving my inherent romanticism amid the deepening existentialist persuasions of my youth.

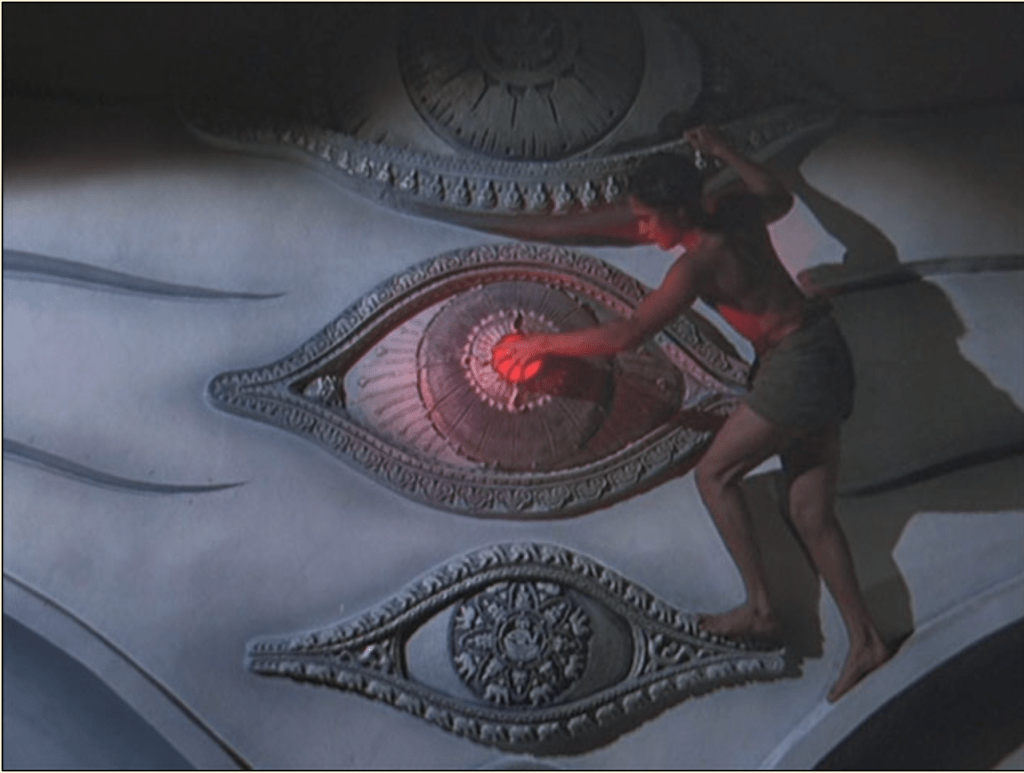

4. ‘The Thief of Baghdad’, 1940, Produced by Alexander Korda (Hungary), starring Indian actor Sabu, British actors John Justin and June Duprez, and German-English actor Conrad Veidt

To me, this film represents one of the most gloriously effective uses of technicolour in the history of cinema, perhaps second only to the 1939 Hollywood classic ‘The Wizard of Oz’. Its alluring, exotic locales and hints of treasure, beauty and mysterious cultures abroad forever incited my thirst for travel. Despite its conformance in four of the five leads to the diktats of the era — a time where Asian and Black actors were still routinely played by white actors wearing yellow or blackface makeup with seriously scary eyebrows — it’s impressive that Korda not only chose excellent Indian actor Sabu for the titular thief, but also used several ethnic Chinese and other Asians as extras in the film, which helped lend this otherwise otherworldly Arabian Nights fantasy an air of authenticity.

‘The Thief of Bagdad’ tells the story of a blind beggar in ancient Basra (in reality, Prince Ahmad of Bagdad) who relies on the help of his dog (in reality, cheeky street thief Abu) to help him defeat the evil sorcerer Jaffar, who has taken over his kingdom and sent his love, the Princess of Basra, into a deep sleep. After they are shipwrecked, Abu frees a genie who grants him three wishes, including helping Abu steal the magical ‘All-Seeing Eye’ jewel. The jewel enables him to restore Ahmad to his throne and be reunited with the princess, freeing Abu to set out for new adventures on a magical flying carpet.

Between its fantastic and adventurous storyline, characterful acting, excellent cinematography, memorable musical score and superb (for its day) special effects, this film earned its place as a much-loved, classic historical fantasy film.

3. ‘Gone With the Wind‘ (1939), Victor Fleming (director), David O. Selznick (producer), starring Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh, Olivia de Havilland, Leslie Howard, Hattie McDaniel and Butterfly McQueen

Based on Margaret Mitchell’s best-selling, Pulitzer prize-winning 1936 novel of the same name, this story of the US Civil War from the perspective of the doomed Deep South and an equally doomed triangular love affair, although recently removed from HBO due to its controversially favourable depiction of slavery in the Old South, is nonetheless an epic Hollywood classic everyone should see at least once.

Told in two parts, the story begins with its spoilt Southern-belle heroine, Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh), surrounded by her bevy of plantation beaus, each keen to join what to them is a cause worth dying for: the defence of their ‘charmed’ (not for the enslaved African-Americans who facilitated their existence, however) lifestyles against ‘those awful Yankees’ in the more progressive North who want to abolish slavery. Scarlett’s selfish, childish nature is contrasted with the serene but godly Melanie Hamilton (Olivia de Havilland), who happens to be Scarlett’s love interest’s, Ashley Wilkes’ (Leslie Howard) intended. As the men run off to war, Scarlett encounters cynical Charleston rogue Rhett Butler, a rich, self-made man who has no illusions about the South, yet who gradually develops romantic delusions about winning Scarlett’s affections. Increasingly, as the war rages on, lives are lost, plantations destroyed, and poverty, disease and the threat of ‘carpetbagging Yankees’ demanding taxes take their toll. Seeing their dreams of victory turn as tattered as the women’s dresses and all her dreams of a life with Ashley lost, Scarlett vows not to let this defeat her.

The second half explores the main characters’ development against the backdrop of the postwar Reconstruction era. They are all older, yet not necessarily wiser: Rhett still cherishes the hope that he and his now-wife Scarlett will be happy; Scarlett still covets Ashley, who is happily married to Melanie; Ashley still dreams of the South as it used to be, unwilling to adapt to their new circumstances as Scarlett has; Melanie still maintains her saintly, blithely unaware love for Scarlett, despite the latter’s desire for her husband; and the O’Hara’s remaining Black servants Mammy (Hattie McDaniel) and Prissy (Butterfly McQueen), are still enslaved, just tireder and in nicer digs. It takes the loss of Rhett and Scarlett’s beloved daughter Bonnie and Melanie’s death to make everyone realise they’ve been cherishing unrealistic ideals that essentially have no real value.

At nearly four hours long, it takes a big commitment to watch it, however I read the novel at least nine times in my childhood and have watched it religiously once a year ever since. Why? Because beyond the annoying and patronising racism of the Old South, the dramatic ‘burning of Atlanta’ and gruesome battle and hospital scenes, and even beyond the undeniably electric chemistry between Clark Gable as Rhett Butler and Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara, it is essentially a story about surviving against the odds, even in the midst of poverty, disease, death — all the horrors of war, which the film certainly does not shy away from — as well as about disappointed and unfounded romanticism. And for that reason, it remains a film that will always inspire me to battle on through my own darkest moments — “Because, after all, tomorrow is another day!”.

2. ‘The Seventh Seal’, 1957, Ingmar Bergman, starring Bengt Ekerot (Death) and Antonius Block (the Knight)

I first saw this arthouse classic in my late teens, not long after I had embraced existentialism, though in fact I was still wrestling with philosophical questions about meaning and the purpose of existence, which ‘The Seventh Seal’ expertly articulates. Set in stark Swedish landscapes and filmed entirely in black and white, it is about as graphic a display of absolutes — in this case, life (symbolised by the travelling players) versus death (the literal person of Death) — as you can get.

As the film opens with its brooding landscape and intense operatic score punctuated with quotes from the Book of Revelations, you are immediately aware it is going to be challenging to watch. However, as soon as the central story commences (Death comes to claim the life of a Mediaeval knight who returns from the Crusades to a plague- and doom-ravaged village; filled with fleshly fears of death and stalling for time, the knight challenges Death to a game of chess and the two discuss life, death and the existence of God), you are drawn into this compelling drama. Meanwhile, their grim discussion is interspersed with scenes featuring the joyful, innocent — and thereby ‘holy’, as Bergman intimates — family life of Jof and Maria, part of a group of travelling players, whose childlike innocence and ‘divinely inspired’ visions make them seemingly impervious to and freed from the existential threat of death.

Perhaps if I had not seen this film, I would have followed through with the logical conclusion of existentialism — eg that there are no absolutes and that life is ultimately meaningless, therefore there is no reason (apart from the fleshly fear of death expressed by the knight) to go on living — however the transcendent image of the joyful, innocent, ‘holy’ family made me aware that indeed, life can be beautiful, and there is hope in human love and childlike trust. It is a choice we must all face at some point, and Bergman makes this point most simply and profoundly.

1. ‘Brother Sun, Sister Moon’, 1972, Franco Zeffirelli, starring Graham Faulkner, Judi Bowker and Alec Guinness, with music by Donovan

This film changed my life more profoundly than any other I have ever seen. Having battled with existential doubt and been challenged by the vision of innocence in ‘The Seventh Seal’, its story of the simple, radical choice of the young aristocratic Italian nobleman Francesco to reject war, ambition and the earthly goods his wealthy merchant family provided to embrace a life of poverty, chastity and obedience in union with God and nature, so exquisitely depicted under Zeffirelli’s masterful direction and enhanced by Donovan’s meaningful soundtrack, made me, like Francis, “see the light” about what is most truly meaningful in life.

The film begins with Francesco having returned from fighting in the warring Italian Mediaeval states of Assisi and Perugia ill and suffering from what appears to be post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the horrors of war and amplified by visions of his rowdy, arrogant past. As he begins to recuperate and spends time in nature, he finds God and begins a deep inner change, eventually catalysing his rejection of his father’s wealth and decision to serve the poor in a memorable scene where, having been beaten after throwing his father’s rich textiles into the street, he strips off entirely and renounces both his name and his family, and walks out of Assisi naked to follow God as an ascetic.

During this period, he becomes friends with stunningly beautiful noblewoman Clare, who ministers to the city’s lepers. Not long after Francesco hears God calling him to rebuild the ruined church of San Damiano, he is joined by other brothers, including Clare, who also takes a vow of chastity, poverty and obedience to join him, forming a similar group of sisters. Ultimately, when he is descried as a troublesome lunatic and summoned to appear before Pope Innocent III (Alec Guiness), the pope memorably acquits him with the line, ‘In our obsession with original sin, we have forgotten original innocence.’

Zeffirelli also memorably directed ‘Romeo and Juliet’, ‘The Taming of the Shrew’, ‘Hamlet’ and the TV miniseries ‘Jesus of Nazareth’, all of which are brilliant films that deserve multiple viewings.

Other films worth mentioning

‘Room With a View’, 1995, James Ivory, starring Maggie Smith, Helena Bonham-Carter, Daniel Day-Lewis, Julian Sands, Judi Dench, Simon Callow and Denholm Elliot — based on EM Forster’s 1908 novel about Edwardian-era Brits in Italy, it is perfectly acted, with beautiful cinematography and a lush soundtrack. Probably my favourite romantic drama of all time.

‘Raise the Red Lantern’, 1991, Zhang Yimou, starring Gong Li — Set in 1920s China, this film introduced the western world to the stunning beauty and talents of Chinese-Singaporean actress Gong Li, and the formidable directing talents of Zhang Yimou. Its exquisite cinematography — where every scene and still is breathtakingly sublime — made me gasp aloud with pleasure. An international treasure.

‘Midnight in Paris’, 2011, Woody Allen, starring Owen Wilson, Marion Cotillard, Rachel McAdams, Adrien Brody, Léa Seydoux, Corey Stoll, Tom Hiddleston and Michael Sheen — Love him or hate him, this is Woody Allen at his best. Rightly won ‘Best Original Screenplay’ for its charming, fairytale-like story of an American writer in Paris who time-travels to 1920s Paris to meet the writers and artists he admires, only to discover through Cotillard’s mysterious beauty that whatever famous period you are in, there will always be another period that someone else considers the true golden age. Brody’s cameo as Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dali is a scream.

‘Aguirre, the Wrath of God’, 1972, Werner Herzog, starring Klaus Kinski, and ‘Fitzcarraldo’, 1982, Werner Herzog. starring Klaus Kinski and Claudia Cardinale — both films concern visionary but ultimately doomed quests in South American jungles made by raving madmen, played to perfection by Kinski and embellished by lush cinematography and musical scores. The first, based on a true story of a tyrannical 16th century Spanish conquistador who leads an expedition down the Amazon in search of El Dorado, destroying everyone as his madness progresses; the second, based loosely on a true story about Irishman Brian Fitzgerald, is about an opera-obsessed madman who attempts to drag a boat overland and bring opera to the Amazon.

‘Death in Venice’, 1971, Luchino Visconti, starring Dirk Bogarde, Bjorn Andrésen, Marisa Berenson and Silvano Mangano — based on the 1912 novella by Thomas Mann but altered so the main character is a composer, allowing for an exceptional classical score including works by Mahler and others, it explores themes of beauty, art, desire and mortality; essentially, unrequited romantic desire.

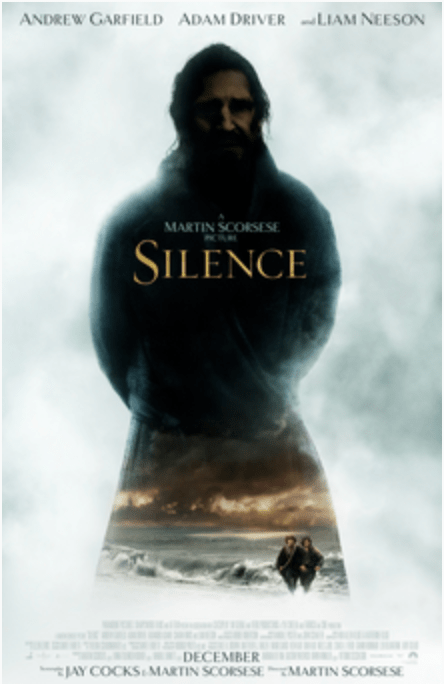

‘Silence’, 2016, Martin Scorcese, starring Liam Neeson, Andrew Garfield, Adam Driver, Tadanobu Asano, Issey Ogata and Ciáran Hinds — this harrowing, emotionally powerful film, based on the 1966 novel by Japanese author Shusako Endo, tells the story of a Jesuit missionary sent to Japan during the time of persecution of Japanese ‘kakure’ Christians following the 17th century Shimabara Rebellion. It has been a key inspiration for the historical fiction novel I am presently writing, set in this period in Japan but from the perspective of a Dutch artist working with the VOC who becomes an unexpected hero when he tries to rescue Japanese Christians from execution.

‘Apocalypse Now’, 1979, Francis Ford Coppola, starring Marlon Brando, Robert Duvall, Martin Sheen, Lawrence Fishburn and Dennis Hopper — A powerful and disturbing 20th century retelling of Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella, Heart of Darkness, transplanted from 19th century Congo to the Vietnam War. A US army captain is sent on a mission to Cambodia to track down and assassinate murderous renegade Colonel Kurtz, rumoured to have gone insane. ‘The horror! The horror!’

‘Wings of Desire’, 1987, Wim Wenders, starring Bruno Ganz, Solveig Dommartin, Otto Sander, Curt Bois and Peter Falk – Filmed partially in colour, partially in black and white, this intriguing film shows two angels watching over a still-divided Berlin from the tops of its buildings, listening in to the thoughts of the mortals below; one of the angels (Ganz) falls for beautiful trapeze artist Dommartin and decides to fall to earth to experience simple human joys and love.

‘The Crying Game’ (1992), Neil Jordan, starring Stephen Rea, Jody Whittaker, Jaye Davidson, Miranda Richardson and Adrian Dunbar, and ‘Mona Lisa’ (1986), Neil Jordan, starring Bob Hoskins, Cathy Tyson, Michael Caine and Robbie Coltrane — I mention these not only because they were both powerful, poignant and well-acted films, but also because I co-hosted a writing workshop with Irish writer-director Neil Jordan in Dublin around the time he was directing ‘Mona Lisa’, and I am incredibly proud of his achievements for Irish cinema and for writing a completely different spin on the IRA.

Of course I could go on and on here, but there is a limit. Having discussed this piece with other writers and friends, I’ve also had several interesting answers about the films that have stayed with them the longest, and why; these have included ‘Sense and Sensibility’ (1995), ‘The Intouchables’ (2011) and ‘Before Sunrise’ (1995). Of course, while everyone’s views are subjective and say as much about them as persons as they do about the individual films, it is ultimately testament to the power of such films that they evoke similar responses in so many others.

So, putting aside the peculiar whims of past or upcoming Academy choices for now: what is it that, to you, makes a film truly, madly, deeply great? Which of the 10 nominated films would you have given the gong to? And what are your own favourite films of all time, and why? I’d love to hear your comments.

Interesting how many of your films are quite old Jane – perhaps it’s to do with the most impressionable age when we watch them, just like music in our teens often being the most affecting. I love films which are based on books but do something different with them – e.g. Room With A View (much lighter than the book) and Sideways (better than the book, I think). Also some Austen adaptations e.g. Sense and Sensibility (also better than the book, though I hate to say it).

LikeLike

So interesting you would say that about Austen and ‘Room With a View’, also one of my all-time fave films – I meant to mention both films but ran out of time, so may have to extend my list (as well as including a few more up-to-date films). However, you are right: I watched all of those films when I was young and going through my various transformative periods of romanticism, existentialism and then my dramatic conversion. I do have a few more contemporary films that have also had significant impacts on me. So what about you? What films have stayed with you?

LikeLike