After a week marked by prolonged social media discussions on how to deal with climate grief, a close friend’s profound grief and despair due to losing her mother to Covid, and an extremely moving vigil to mourn the loss of a uniquely beautiful, much-beloved and irreplaceable site of ancient woodland, the below is a meditation on these various forms of grief — climate grief, personal grief, and solastalgia (loss of place, specifically Jones Hill Wood) — and how to work through it.

Jones Hill Wood: a very poignant solastalgia

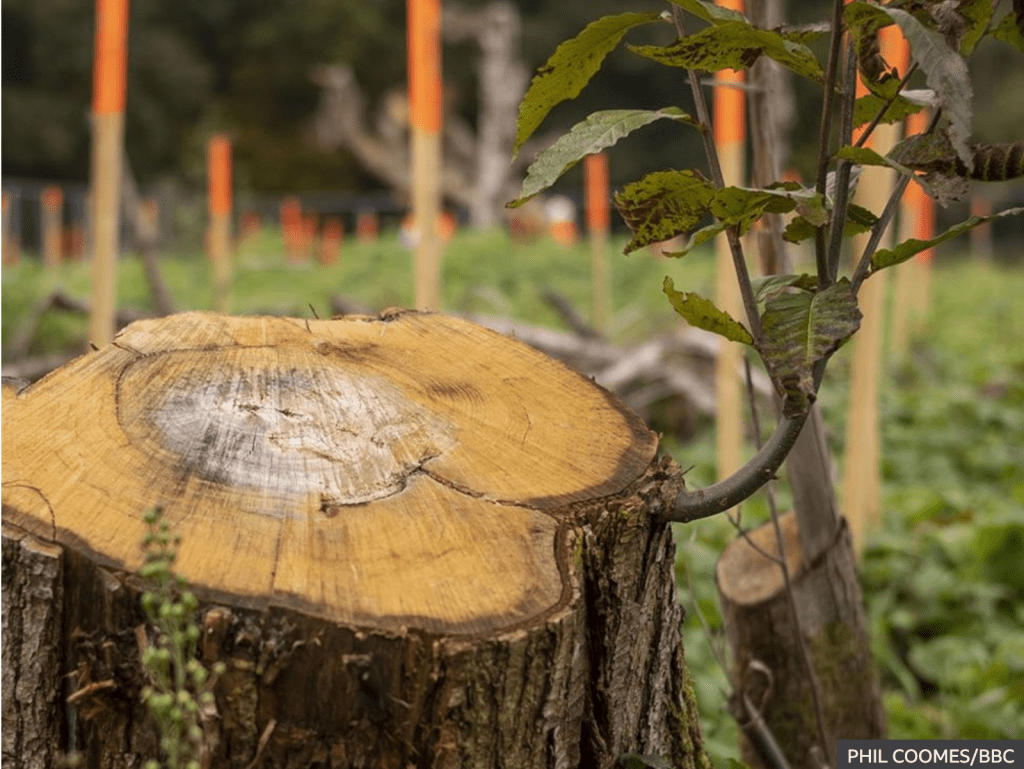

I recently attended a vigil at Jones Hill Wood in Wendover, along with some 30–40 people — or perhaps there were more in the trees, or huddled in cars and tents. Sadly, even as we sang, shared poems, stories, verses and personal remembrances, the chainsaws could be heard felling in the background, greedily destroying this incredibly beautiful ancient woodland, described even by its Government-authorised ecocidal murderers as “a habitat of principal importance”.

For all who have ever visited this wood — the inspiration for beloved children’s author Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr Fox (the author lived in nearby Great Missenden, and one of the book’s principal characters is named Bunce, supposedly after farmer Kevin Bunce & Sons, on the edge of whose farm the wood sits) — Jones Hill Wood is a truly magical, irreplaceable site. For those of us who have been fighting long and hard to preserve it — even more so for the many who have been living here in the camp for over a year, as powerfully documented here — the beauty of this place has left a deep mark on our souls. The connection is so strong that its threatened loss leaves an overwhelming sense of grief and heartache — the kind of ‘homesickness’ now described as solastalgia, which is recognised as a key component of climate grief.

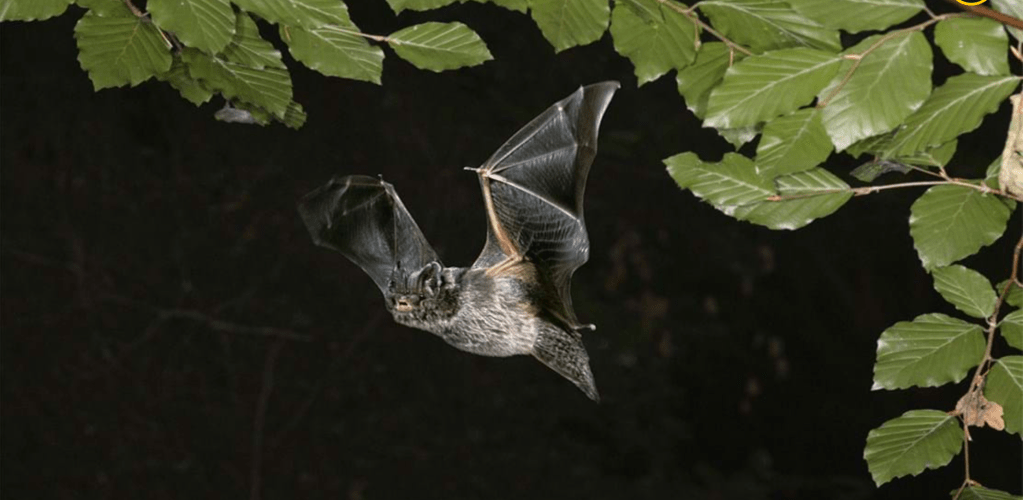

Tragically, despite the endless hard work by a crack ecological team in recording evidence of the increasingly rare and threatened Barbastelle bat (Barbastella barbastellus), supposedly protected by law (the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, for one), our hard-fought legal case against Natural England — which only recently resulted in an injunction being granted by sympathetic judge Justice Lang to stop the felling until 24 May — was overturned by HS2 ally Justice Holgate. This meant HS2 would be allowed to resume their deadly work with immediate effect, nesting/roosting season notwithstanding.

And so we gathered to grieve the loss of this precious habitat, a “mix of semi-natural broadleaved woodland dominated by beech”, and also home to oaks, ash, rowans, elders, holly, hawthorn, cherry, bluebells, foxes, glis glis, badgers, nesting birds, Natterer’s and other bats, and many other precious flora and fauna. We sat in a loose circle on the ground, near the fence HS2 workers keep moving (that part of the land belongs to Mr Liberty; they are in fact stealing an extra 1.5–2 metres all around it supposedly for ‘mitigation’ [their idea is translocate the ancient soil, a concept that is rejected on principle by the Woodland Trust and other leading ecologists — and don’t get me started on HS2’s ‘ecologists’, whom I have only ever observed arriving at a site, poking a stick in a tree or bush, shaking it around and then departing]; in reality, this further unlawful land grab is merely so they can destroy yet more ancient woodland to make way for a temporary haul road). Each person who wished to do so took turns sharing, all holding flickering candles. Local resident and bodging expert Stuart placed a crucified Mr Fox on the fence as a gentle protest.

One woman began by reeling off a few of her poems, hard-hitting rhymes that resonated with all of us. I read out the words of Psalm 24, which had echoed upliftingly in my head after a previous despair-filled episode in this year-long battle with HS2 (the infamous ‘Battle of the Beancan’). Mark Keir shared the good news that at least one protestor’s case had been dropped. Val and Sylvia led us in a few gentle songs. Ghost read a history written by a World War II child evacuee of a local farm, the owners of which have since been evicted and the farm is soon to be destroyed by HS2. Jo placed a small cross on a temporary ‘grave’ made with a few feathers, twigs and stones, thanking many significant people – valiant local reporter Ann of Wendover, the team of volunteer ecologists tracking the bats, the helpful food suppliers, and all of us who cared enough to come, whether locally or from far away.

“But, take these several beings from their homes.

John Clare

Each beauteous thing a withered thought becomes;

Association fades and like a dream

They are but shadows of the things they seem.

Torn from their homes and happiness they stand

The poor dull captives of a foreign land.“

A visitor from Hemel shared memorably about how he had realised our spiritual energy never dies, but goes into something else. He said he had been pondering which animal he would want to come back as, but had finally concluded he would want to come back as a tree – “because then I would be giving oxygen to the world – and maybe some of you would climb up among my branches, and save me so I can keep on saving you”. Nearly last, but not least, legal warrior Kestrel stated that “until the last tree has been cut down, we will keep fighting”. That is indeed what all present have been doing fervently for a year or more, ever since the camp at Jones Hill Wood (JHW) was first erected.

And yet recent conversations reveal that responses to ecocidal grief and loss vary widely. Despite those of us who were present at this vigil – some, like me, local; others travelling for hours from all over the UK – frequently shouting out tirelessly for witnesses to come and share our grief, to assist us in honouring this magical wood before it is nearly completely destroyed, we encountered the usual excuses from many – “I can’t bear to see it – it makes me too upset”, “I’ve already done all I could”, “You can’t fight it, the system is totally corrupt”, “It’s a done deal, you’re wasting your time”, etc etc. I have lost much time and psychological energy this week contending with comments on social media from some who sadly chose to take my pleas for support and physical presence at JHW as an effort to make them feel guilty. This at times has felt deeply alienating, as what I had mostly hoped for was empathy. Grief of any kind is always so much harder to bear when those we think will support us don’t, for whatever reason. It makes the loss so much harder to shoulder.

But as I and several other vigil attenders commented, out of all the horror of this abysmal ecocide and the shattering loss of our legal battle to protect this ancient wood and its creatures, the very best thing to come out of it has been the sense of kinship, deep empathy, fondness and connection we have all felt towards each other in our shared grief and purpose.

I remember once hearing a saying that has stuck with me ever since, particularly whenever I have discovered a kindred spirit after feeling alienated because of my views or beliefs: A friend is someone who sees the same things you do. I may not otherwise have much in common with everyone present — we represent a wide range of creeds, colours, ages, tastes, education levels, skills, geographies and even nationalities — yet here in this wood, sharing this moment of grief together, we were all indeed one, and the same. As Jo said, “You’ve all become my family now.”

Climate despair: Suffer in silence or galvanise in action?

Probably one of the most profound things about grief is that it is a deeply personal issue – and being that we are all unique, one-of-a-kind individuals, we all have different ways of processing and responding to it. When our friends or loved ones are overwhelmed by grief, sadness and loss, we have to allow them to go through the process of grieving (as outlined below) in their own way and time. All of our good or best intentions, or efforts to cheer them up, can never make the pain go away — and in some cases, it may even make it worse. Therefore, if we love them, we have no other option but to practise “the radical act of letting things hurt”. There can be no moral judgement or standard, one-size-fits-all timetable for how long it takes to work through grief — it is not something one can simply ‘snap out of’ just because someone else says we have to.

The differences and similarities in the processes of dealing with grief are very clearly seen when it comes to dealing with the topic of climate grief, the emotional toll of which is now finally being recognised as a genuine psychopathological illness. According to a 2016 report on climate change and mental health, “perhaps one of the best ways to characterise the impacts of climate change on perceptions is the sense of loss”.

As mentioned above, solastalgia is the fancy scientific name for the sense of abject desolation arising from the loss of a significant or emotively charged place (such as JHW) — it is a psychological phenomenon most keenly observed in those forced to leave their homes or familiar terrain as a result of disaster, for example war, persecution, genocide, pollution, drought, famine, floods, avalanches, rising sea levels, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions and deforestation. Alas, we now know this phenomenon will only increase and become even more pervasive the hotter the planet gets, the more unsustainable this Earth we call ‘home’ becomes.

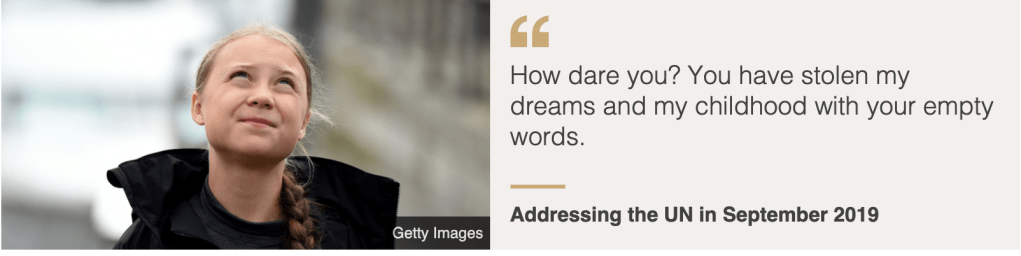

Ever since climate change started making international headlines — perhaps beginning with Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg‘s decision to sit alone outside her school in August 2018 holding a placard announcing Skolstrejk för klimatet (‘School strike for climate’) in a concerted protest about global leaders’ refusal to address the looming climate catastrophe — the world has been deeply divided about how to respond to climate grief and anxiety. In just 16 months, Greta’s actions launched a global youth protest movement that inspired over 4 million people to join the global climate strike on 20 September 2019. She met the Pope and the US President (then the resolutely climate-sceptical Donald Trump), and also became Time‘s 2019 Person of the Year — pretty impressive results for a then-15-year-old girl with Asperger’s!

However, perhaps Greta’s most significant achievement has been her ability to give voice to the sense of rage, futility, despair and grief many of us now feel about the inevitable losses we will all soon experience as a result of climate change. “How dare you?” she thundered at world leaders gathered at a UN Assembly in September 2019, “You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words.” She fearlessly and blatantly accused them of failing to act, of fiddling while the entire planet burns: “Sorry, you’re not doing enough!”

Greta’s courageous activism has also helped give birth or fresh impetus to many radical environmental groups such as Extinction Rebellion (XR), whose catchphrase, ‘Love and Rage’, sums up the emotional status behind this global effort to impact corporate and political decision-makers to do more to combat climate change before it is truly too late. Motivated by a deep sense of alarm, rage and grief about the coming environmental apocalypse if sufficient measures are not taken to prevent temperatures rising above the pre-industrial level 1.5°C threshold, as outlined in the 2018 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report, XR has consistently demanded the formation of a Citizen’s Assembly that will enable climate-alarmed citizens to take action to avert disaster.

As with any large-scale, global movement of diverse human beings, there have been some disagreements and diverging paths within XR; it has now developed several sub-groups, of which HS2 Rebellion is but one*. However, XR officially espouses a welcoming, tolerant and non-shaming/blaming culture that seeks to balance occasionally provocative, militant and/or disruptive activism — such as the October 2019 Canning Town tube incident, which divided many members and is currently perceived by several of its leaders as misguided —with a loving, self-compassionate emphasis on regenerative culture (or ‘regen’) — practising deep levels of community, interpersonal and self-care in order to be able to recuperate from intense actions or long-term resistance, and thus become more resilient in the face of adversity and hostile reactions so as to be able to continue the fight.

While the effect of such divergent movements has perhaps been to lessen the unity and thus overall impact of XR — not least also significantly hampered by the Covid-19 lockdown, as well as UK Government moves to add limitations and restrictions to democratic rights to protest — there have also been simple, but occasionally marked, differences in the practices, tools and methods its diverse individuals have chosen as aids in processing climate grief. Some are perhaps more naturally inclined to direct or ‘aggressive’ political actions, whereas others prefer a gentler path of helping to heal the Earth through a range of nature-friendly efforts such as rewilding or other ecologically important and sustaining work. Others are more comfortable, skilled and effective in petitioning, lobbying — for example, attempting to persuade MPs to back the Climate and Ecological Emergency (CEE) Bill — or utilising social media in “armchair activism”.

Yet whether XR rebels are happily risking arrest by engaging in radical, potentially dangerous actions such as lock-ons and recently tunnelling under Euston Station to get their points across, or are patiently doing most of the time-consuming legal or political legwork behind a computer screen, the effect for all of any prolonged interfacing with the spectre of potential planetary annihilation is often severe burnout, coupled with an overwhelming and psychologically disabling feeling of climate despair. Aware of the capacity for this, XR set up an Emotional Support Network to help activists who are burned out or so climate grief-stricken they are unable to function. This resource, along with other regenerative practices such as simply spending more time enjoying and appreciating the very nature we are fearful of losing, is seen as the best ways for individuals to combat climate grief.

Along with our common mortality, another facet of being human is our need for social connection, even in the midst of overwhelming and often isolating grief. This very human need for connection is so deeply woven into the fabric of our psyches that even the most introverted or rugged individualists need that sense of connection to manifest somehow — for example, American naturalist Henry David Thoreau, influential author of classics Walden and Civil Disobedience, who spent nearly his whole life living alone in a cabin in the woods by himself, still emerged with books eager to impart his story to society and ultimately change it as a result.

Unsurprisingly, XR itself arose from a small group of activists, friends and academics who all saw the same thing — the climate and ecological emergency — and, led by Gail Bradbrook and Roger Hallam, decided to do something about it collectively. Although ideas for something similar had been around for a few years, in October 2018, they decided to spawn a movement that could help empower others to “be (part of) the change you want to see”, and so officially launched XR.

Yet some will still ask: Why act? If the world will all end soon, and we are all powerless to stop it, what is the point? Shouldn’t we all just stay in a place of grief, embrace what little time we have left doing the things we love with the people we love? And what about our need to take time simply to enjoy the beauty and glory of this precious yet fragile planet, while we still can?

Of course, this is all true — and, as XR’s experience and tenets testify, any programme of activism MUST be balanced with regen practices, which for those who experience profound climate grief should certainly include time spent in nature. As has been noted:

“We are only just beginning to understand the effect of nature on human health. One in six of the UK population suffers from depression, anxiety, stress phobias, suicidal impulses, obsessive-compulsive disorders and panic attacks” [not to mention addictions caused by over-reliance on various substance — food, alcohol, drugs, nicotine, sex, etc]. Treating such mental health issues cost the National Health Service £12.5bn, and the economy up to £41.8bn in dealing with the human costs of reduced quality of or loss of life. Yet studies show that time spent in nature [even for hospitalised patients who have a view of nature form their windows] has the power to alleviate most of the symptoms of these disorders.”

So, for those feeling overwhelmed with personal or climate grief or stressed by thoughts of a potentially uninhabitable planet for their children and grandchildren, time out in nature is essential.

However, beyond the ever-present need for regen, the general consensus among the climate-concerned/climate grief-stricken (see below) is that the best tonic for the sense of futility and the ever-present guilt of “not doing enough” is action — specifically local, political or community-based actions that have a clear focus and an immediately observable, beneficial effect on the environment. Whether this will also involve more radical behaviours such as smashing windows, stopping trains or living in a treehouse in a threatened woodland is entirely up to the will, personalities, and mental/physical abilities of the individual — clearly, such actions may not be suitable or acceptable for everyone.

The five stages of grief: personal and climate grief

For those who have either not yet made the leap from awareness of climate change to alarm to despair and then to activism — as per my own personal trajectory, and that of many other environmental warriors and XR members I know — the process of working through climate grief follows a very similar pattern to Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s seminal 1969 work on grief, On Death and Dying.

Kübler-Ross’s outline of the five major stages of grief is now seen as a classic paradigm for counsellors seeking to help alleviate the depression and other mental health issues grievers experience. The received wisdom regarding these stages is that they tend to go in a cycle, and are not always linear — in fact, some may be repeated on and off as individuals process their grief. Some people experience all of the stages, occasionally simultaneously, while others may only experience a few — and some may experience none at all. However, as these are now accepted as fairly standard aspects of the grieving process, they are worth noting in any discussion of grief, as explained below.

I have summarised these and also made reference to the climate grief variation of this model, as first articulated by University of Montana professor Steve W. Running, who was a lead contributor to the Nobel Peace Prize-winning 2007 IPCC report.

1. denial — shock, fear, avoidance, confusion, elation

2. anger — frustration, irritation, anxiety

3. bargaining — struggling to find meaning, reaching out to others, telling one’s story

4. depression — overwhelmed, helplessness, hostility, flight

5. acceptance — exploring options, new plan in place, moving on

Denial

Shock and denial are initially helpful in that they help to cushion the blow when you have suffered a really painful loss, such as the unexpected death of a loved one. You experience a kind of numbness where you can’t believe what has happened and how it has irrevocably changed your life. Denial is essentially your psyche’s way of saying, “I can’t handle this now”. But as it is only once the bandages are removed that the healing process in your body will begin, the same is true of how your psyche heals from grief. As the shock and denial start to fade, the healing process can begin.

When this stage is interpreted in the climate grief version, this is reflected as complete denial of the existence or reality of climate change. People simply refuse to accept that it is happening or to recognise the impacts of manmade greenhouses on a warming climate, and instead blame any temperature rises on natural processes. While there are many types of climate change denier and climate conspiracy theorists, typically this is intertwined with the vested interests of the fossil fuel industry. For the most part, those who reject the idea that climate change is happening tend to do so because they are aware on some level that if it is true — as those of us now familiar with the science know it is — it will necessitate massive amounts of personal and systemic change. And we all know that change of any kind is a very scary proposition for many, hence the resistance to the truth.

Anger

After the initial shock and denial subsides, suppressed emotions begin to arise — with angry thoughts being a predominant feature: Why me? It’s so unfair! Where are you God! How could you let this happen? In the midst of their confusion and distress, grievers often misdirect blame onto others to avoid experiencing the painful sense of helplessness and frustration at not having been able to stop the loss. Yet while anger is not always healthy, the anger connected with grief is actually a vital part of the healing process. Giving voice to feelings of rage helps channel the griever’s awakened energies into making the painful but necessary changes that will ultimately help the griever move forward.

Anger is also an extremely significant aspect of the climate grief cycle. Once it becomes undeniably evident that climate change is indeed happening —far faster and with far more devastating consequences than any single country or group of leaders is presently prepared to deal with —sheer, incandescent rage is typically the first emotion most people feel as the veil of denial lifts and acceptance occurs. Greta Thunberg’s incensed “How dare you!” echoes exactly the feelings of everyone who has suddenly woken up to the fact that all the dire scientific warnings and climate change models — many of which have actually been around since the 1970s, with varying degrees of accuracy — have been steadfastly ignored, hidden or covered up by world leaders and a heavily fossil fuel-dependent society. It is often this anger that prompts people to join activist groups such as XR (perhaps quite logical, then, that its catchphrase is ‘Love & Rage’).

Bargaining

The next classic stage of grief is bargaining. This often manifests as an attempt to ‘make a deal with God’: Please God, if you can only do just this one miracle, I promise to be a good/better person forever. You falsely believe that by negotiating, by offering to make some major sacrifice or commitment, it will enable you to get your life ‘back to normal’ (eg before the event that caused the grief) or forestall the grief in some way.

Most of this bargaining is fed and empowered by guilt, and attended by endless ‘if onlys’: If only I had done x, y wouldn’t have happened. My loved one might still be here today if only I had been there to get him/her to the hospital in time. If only I had not gone back to get my keys, the accident would never have happened. If only I had listened to my instincts and got him to see a doctor sooner. If only I had left work on time, I might have been able to save her. The list goes on. And on. Depending on their personality, cultural background and personal capacity for guilt or ‘navel-gazing’, some grievers can get stuck in this stage for a long time.

For those who began their journey from a place of climate change denialism and have now (technically) accepted it as a reality, the bargaining stage tends to take some form of reasoning that perhaps it is not really quite as bad as scientists predict. The bargainer will likely attempt to put a positive spin on such predictions by asserting that, for example, the warming of normally frozen locations might be good in that it will open up new places (Antarctica, for example) to tourism or human habitation. Or they may place their hopes in their political leaders’ commitment to achieving net-zero carbon-neutrality targets by 2050, or in other greenhouse gas-reducing solutions such as renewable energy technologies.

Depression

The penultimate stage is the most common, immediate and well-recognised form of grief. Those who have suffered a profound loss of any kind may speak of having their hearts broken, of feeling they are no longer able to go on, of feeling life no longer holds any joy or meaning for them, of being unable to stop crying, or of feeling overwhelmed by a sense of hopelessness, but not wishing to talk about it. They may feel as though a heavy fog has descended on them, and they may not wish to get out of bed or attend any normal activities, but instead seek to withdraw from others.

Although depression usually has the effect of flattening one’s mood, it can also manifest in many ‘hidden’ ways, such as a seemingly out-of-character or unnatural elation. Sufferers may seem agitated, extremely anxious or fearful, or physically affected such that they are no longer able to eat, sleep or work. The simplest tasks seemingly become impossible. Often, suddenly bereaved wives or husbands may not live long after their partner’s death, whether through desire to be reunited with their loved one in the hereafter or a simple loss of the will to live.

At this point, some may try to alleviate these unbearably painful feelings by turning to drink, drugs, sex or other addictive substances or behaviours, which only work as a mask in the short run, delaying or preventing the person from dealing with or moving on from their actual grief. In some cases, the secondary problems arising from reliance on these methods can take over, causing far more severe long-term issues such as complete mental or marital breakdown, job or home loss, physical injury or illness, or even death.

In fact, it is probable that depression is a constant throughout the grieving process; even when moving forward to the final stage, a sudden memory or reminder of the loss can trigger fresh feelings of depression or sadness.

The depression stage of climate grief will plunge some into a state of despair, alternating with panic about the inevitable and irretrievable doom of the planet. They often feel overwhelmed and bewildered by what seems an impossible situation, and find themselves unable to think clearly about or act to find any potential solution. However, even if they reach this state, they will eventually realise that it is simply impossible to live here forever — they must stir themselves to take some kind of action, however small, to feel satisfied they are at least ‘doing their bit’ to fight the situation. Doing so is a step forward, as it is effectively empowering them for the next step.

Acceptance

In Kübler-Ross’s final stage, the griever eventually works through the gamut of their feelings and begins to move into acceptance of the loss. While never admitting the loss as okay in itself, they begin to realise that life does go on, and so must they. They feel that despite the not-okay-ness of the loss, they themselves will eventually be okay — and they accept that that is what the person or thing lost would wish for them.

This time of adjustment will be marked by many ups and downs, by good days and bad days. Sometimes the sadness will flood them anew with fresh feelings of pain, but it will eventually lift. During this stage, people may find new friends or activities that, while never replacing the loss, will help provide a fresh focus and impetus to get on with the business of life. This process can eventually lead to a new direction or new purpose, for example remarriage or rebuilding one’s life in a new setting.

Those who have accepted the scientific reality of climate change and the present ecological emergency, and have begun to move forward from a place of climate grief and despair, generally recognise that they will need to make some necessary and radical changes to their own lifestyles. Frequently, having begun this process, they also seek to help and educate others, often by advocating for change through personal, local national or international policies or the political arena. They may become active in championing new technologies or even resuming ancient practices that seem to offer viable solutions, for example rewilding as a tactic to reduce biodiversity loss by the reintroduction into uninhabited landscapes of specific species such as bison, wolves or beavers.

For those at this stage, the only ‘solution’ that is non-viable is not doing anything — for them, inaction is simply unacceptable. As such, this final stage of activism, when balanced with understanding others who have not yet reached this place, acts like a resolution to the famous existential dilemma of ‘doing’ versus ‘being’: in this case, to be IS to do, and to do IS to be.

Alas, the very fact we are human means we are mortal — we all, at some point, will die. So, too, will everything in this present world. Even if we had succeeded in preserving the injunction against HS2 — or even yet win a further appeal, as the legal team are still working on it — the trees and creatures we gathered at Jones Hill Wood to honour will not last; they are made of the same perishable materials we ourselves are. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, atoms to atoms, Et in Arcadia ego. Yet it is the very fleeting essence, fragility and transitoriness of life is what gives it its greatest beauty and poignancy — like butterflies who hatch and spread their gorgeous wings but briefly, only to spawn eggs and then die within days, weeks, months or a year at best.

For those who believe in the resurrection as I do, who are persuaded that there is another life beyond this ‘veil of tears’, there is some consolation in knowing that death is not the final story, that indeed, “There is hope for a tree; though it is cut down, it will sprout again, and its new shoots will not fail” (Job 14:7). Yet even knowing that spiritually or intellectually doesn’t always immediately lift the deep sense of loss and distress we feel when something or someone we have loved and invested so much hope, tears and fervent prayers in saving leaves us alone finally and is with us no more.

“For there is hope for a tree; though it is cut down, it will sprout again, and its new shoots will not fail.”

Job 14:17

Personally, I am deeply grieved by every single evidence of roadkill; it literally breaks my heart every time I drive past a dead bird, badger, deer or squirrel on the side of the road. While it is comforting to know Jesus said, “Not even a single sparrow falls to the ground without your Father knowing about it” (Matthew 10:29), it is less comforting to consider all the human injustice and corruption behind the destruction of our natural world, which is seemingly ‘allowed’ by God — not to mention the sense of betrayal occasionally felt because of unanswered prayers or unsympathetic humans. I have prayed fervently every day for HS2 to be stopped, for some kind of miraculous reprieve to save Jones Hill Wood; in this case, we nearly thought we had succeeded in stopping it, so the blow of the legal reversal and the imminent destruction of the wood feels incredibly disappointing.

Yet here we are, still fighting, still hoping, still praying. As Kestrel had said, “Until the very last tree is cut down, we will keep fighting.” For as the grief model we have looked at tells us, this is really the only way forward for such a profound place of grief.

© Jane Cahane 2021

*As a movement largely populated by either relatively well-off youths inspired by Greta or older activists often characterised as ‘aging hippies’ — many of whom have continued protesting various ecological, humanitarian and military causes since as far back as the late 1970s — XR has sometimes been criticised as being “too white”. Following the horrific, racist-inspired murder of black hip-hop artist George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police in May 2020, XR began to embrace the Black Lives Matter movement in addition to the vegan movement now under Animal Rebellion, another XR division.

Someone in my writing group this morning shared this powerful poem by Maya Angelou – so sharing here:

When Great Trees Fall

When great trees fall,

rocks on distant hills shudder,

lions hunker down

in tall grasses,

and even elephants

lumber after safety.

When great trees fall

in forests,

small things recoil into silence,

their senses

eroded beyond fear.

When great souls die,

the air around us becomes

light, rare, sterile.

We breathe, briefly.

Our eyes, briefly,

see with

a hurtful clarity.

Our memory, suddenly sharpened,

examines,

gnaws on kind words

unsaid,

promised walks

never taken.

Great souls die and

our reality, bound to

them, takes leave of us.

Our souls,

dependent upon their

nurture,

now shrink, wizened.

Our minds, formed

and informed by their

radiance, fall away.

We are not so much maddened

as reduced to the unutterable ignorance of

dark, cold

caves.

And when great souls die,

after a period peace blooms,

slowly and always

irregularly. Spaces fill

with a kind of

soothing electric vibration.

Our senses, restored, never

to be the same, whisper to us.

They existed. They existed.

We can be. Be and be

better. For they existed.

Really sad to see what’s happening at Jones Hill Wood. HS2 needs to be stopped – too many environmental crimes being committed!

LikeLike

Thank you Verel – let’s hope more people donate via the reshared crowdfunder link – and watch the link to the powerful video your team produced too. Apparently HS2’s sham ‘translocation’ mitigation efforts have failed as their greenwash-motivated saplings are all dead or dying 😦

LikeLike

Excellently explained with passion and love for all beings. I’m sure this will be helpful to many,

LikeLike

Thank you so much Cindy – also for the chat today. If you think of anything I could or should add, let me know 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you Verel – let’s hope more people donate via the reshared crowdfunder link – and watch the link to the powerful video your team produced too. Apparently HS2’s sham ‘translocation’ mitigation efforts have failed as their greenwash-motivated saplings are all dead or dying 😦

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing this Jane. And for all your efforts to save Jones Hill Wood I had never thought on the connections across griefs that you have so eloquently drawn here. And you are so right in that eventually we can no longer not act.

LikeLike

It reminds of the lyrics to Joni Mitchell’s

LikeLike

It reminds me of the lyrics to Joni Mitchell’s ‘Big Yellow Taxi’: Don’t it always/seem to go/you don’t know what you’ve got till its gone/they paved paradise, put up a parking lot (or in this case a high-speed railway, which by the time it is built will be a train to nowhere, used by no one (as no one will be sble to affotd it, and anyway it doesn’t stop anywhere between London and Birmingham, so will likely only be used for freight/the very rich). So much devastation for so little benefit – it is truly heartbreaking.

LikeLike

That’s a great article – well written and researched. I have one point to possibly correct. XR was officially established in May 1918. But it was around as an idea for around 3 years before it was launched in October 2018. I seem to remember reading somewhere that Greta Thunberg approached them for advice on the climate strikes, rather than XR approaching Greta? It’s not of major importance, but I thought I’d flag it up 😁

LikeLike

Hi Carolyn,

Thanks for your comments – will check that out re Greta and change as necessary. Btw, did you mean to say XR was established in 1918? Or is that a typo? I was actually very surprised to read that it was not officially organised until 2018, as I had assumed it would have been around earlier – so adding your change about the earlier idea makes sense.

LikeLike

Thank you Carolyn – will try to make those amends soon. Have been busy with other writing projects so have neglected my blog a bit, will try to amend that soon!

LikeLike

This article brings together personal and climate grief with mental health, faith, politics and environment in a way that touches the individual and communal soul and is deeply touching and moving. Thus grief and action, dispair and hope. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your comment, David. I confess I myself alternate between each of those responses, though I am grateful that the three that remain – faith, hope and love – are what keep me engaged in the fight.

LikeLike