What began as an intended series of light-hearted travel-and-food blogs (it still is, in part – see rijstaffel recipe below) has now become a compendium of thoughts and reflections on Amsterdam and its impact on the world (and on me). That is because it is both a chief location for the historical novel I am writing (as explained below), as well as a place in which I formerly briefly lived, and which radically altered my life. Therefore, I invite you to take from this what you wish and leave the rest – like a liquorice all-sorts, some flavours may appeal more than others!

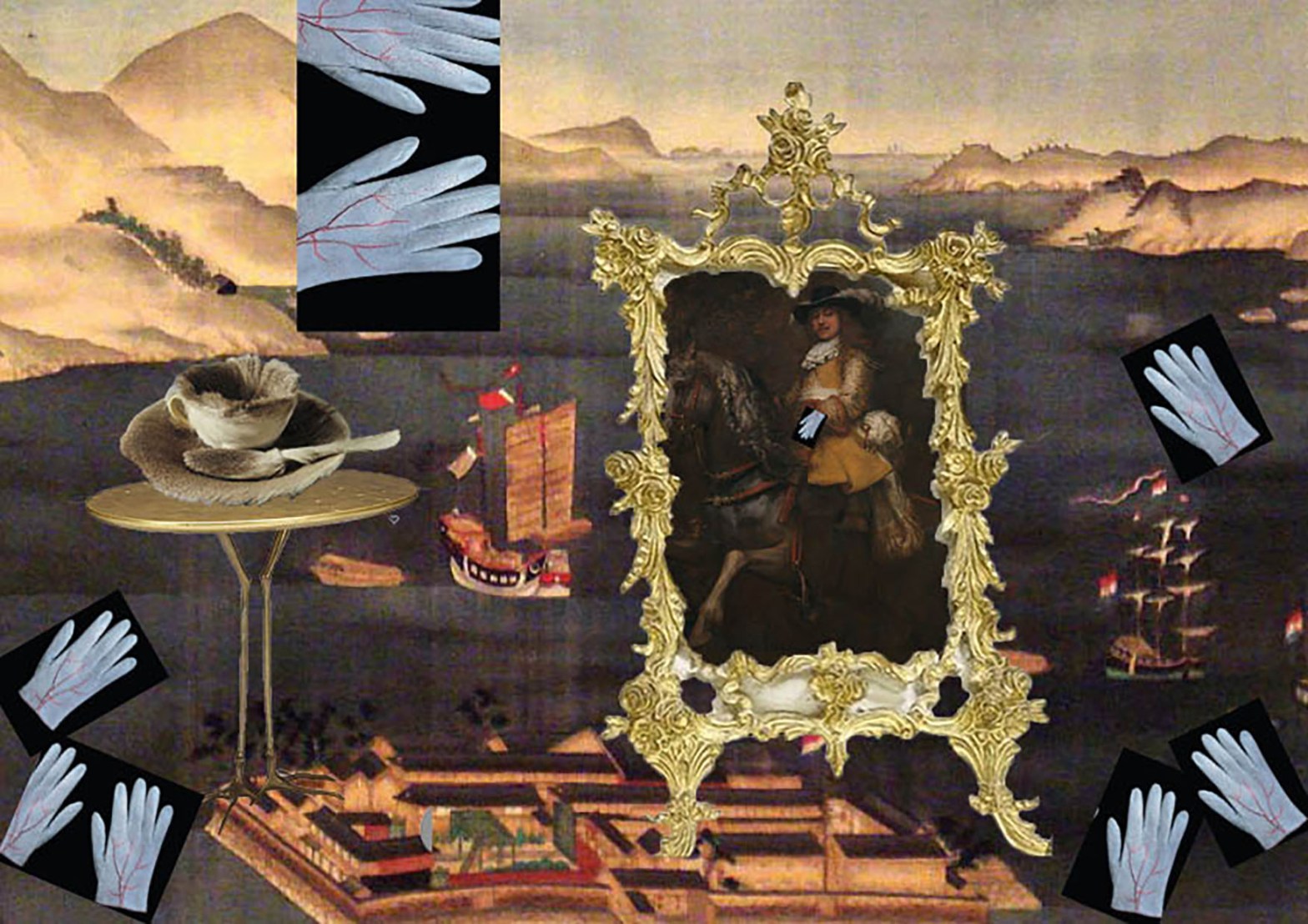

Since mid-October, when an ornament on display at the ‘Kimono: From Kyoto to Catwalk’ exhibition at the V&A gave me the initial idea and inspiration, I began working on the preliminary concepts, genres, character sketches and plotting for an historical novel, which is set in mid-17th century Amsterdam and Japan. (Note: The above image is a collage I created during a recent Shoal of Art session where we were looking at surrealism; as I had just come fresh from my research, the image I created ended up being a mix of Dutch-, Japan- and VOC-related paintings with some of Meret Oppenheim’s surrealist creations, including her blood-stained gloves – which I decided are a perfect metaphor for the ‘staining’ power of colonialism.)

As I’ve discovered, writing an historical novel requires a tremendous amount of research and total immersion into the period, locations, conventions, clothing, habits, morals and attitudes to make the characters believable and as factually accurate as possible (some are based on real-life characters). This can be both fascinating and frustrating. I’ve already learned quite a lot about my subject(s) and the time period, as well as some of the conventions of historical fiction, but I have also realised how even tiny details require an awful lot of time to find on a Google search, and how easy it is to get sidetracked or fall down research rabbit holes in the process. That is one reason for sharing some of this excess information here – it’s a golden opportunity to tell rather than show!

To aid my progress, I’ve joined an online writing group – the London Writers Salon (it’s called that, even though many participants are actually based in the US, Europe and further afield) where you log on to Zoom and write collectively for a solid hour, with a few minutes’ check-in with other writers at the beginning and end. It’s perfect for writers like me who often write best when held to account by others or to an external deadline – and while it is a different incentive to the paid writing commissions I do as a freelance journalist, copywriter and editor, it still gives me a deep sense of satisfaction in setting and achieving goals (I am still working on getting my novel research and plotting, etc NaNoWriMo ready by January – but am nearly there).

“Remember this year? It was a good year, actually. This was the year you stopped waiting around for things to happen. And somehow, as soon as you stopped waiting, as soon as you started doing things, making things, claiming your own space, speaking up for yourself? That’s when your real-life began.”

———Heather Havrilesky, How to be a person in the world

Writing a novel is something I have intended to do all my life, but have somehow been too distracted (usually with salsa, which of course I cannot do now) or discouraged (eg not believing in my message or talent) to get down to it. Therefore, I am grateful to the coronavirus for giving me the incentive to forget all that and get on with it. This quote from a recent LWS session has really resonated with me: “Remember this year? It was a good year, actually. This was the year you stopped waiting around for things to happen. And somehow, as soon as you stopped waiting, as soon as you started doing things, making things, claiming your own space, speaking up for yourself? That’s when your real-life began.” (Heather Havrilesky, How to Be a Person in the World).

Being that my novel will focus on the explorations of new worlds, among other things, here’s to all of us continuing to explore and discover the ‘brave new worlds’ and exotic riches of creativity within us all, and to a new year full of new beginnings!

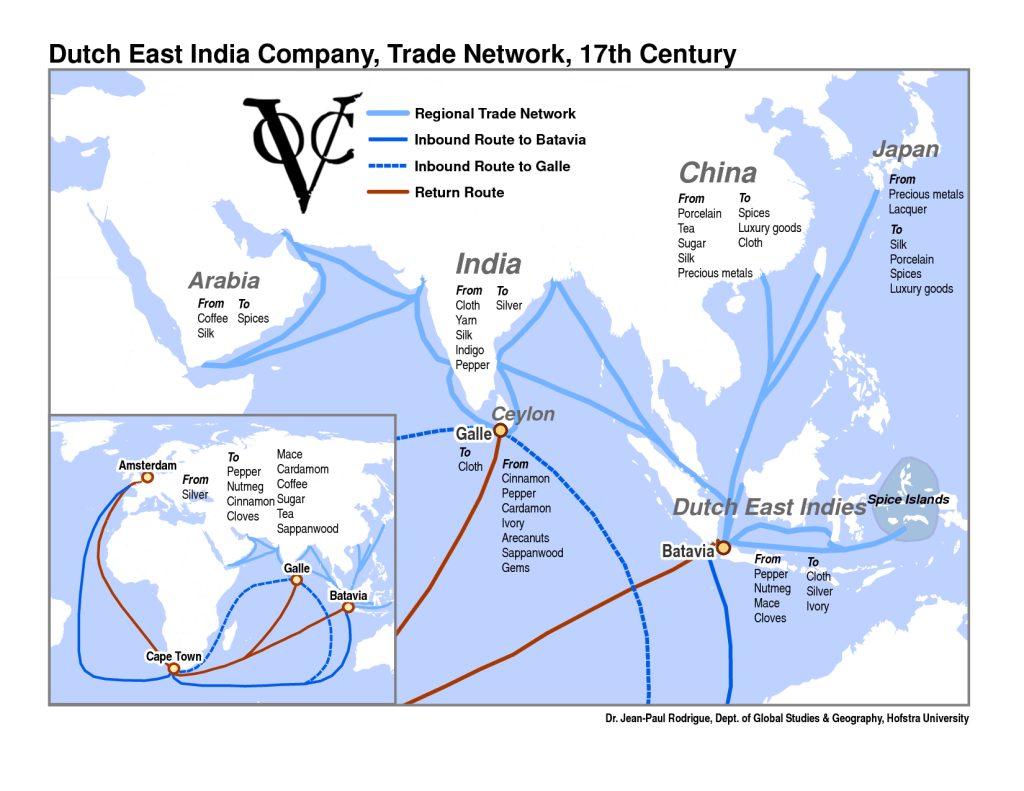

Travel and spices: how a craving for exotic flavours led to capitalism

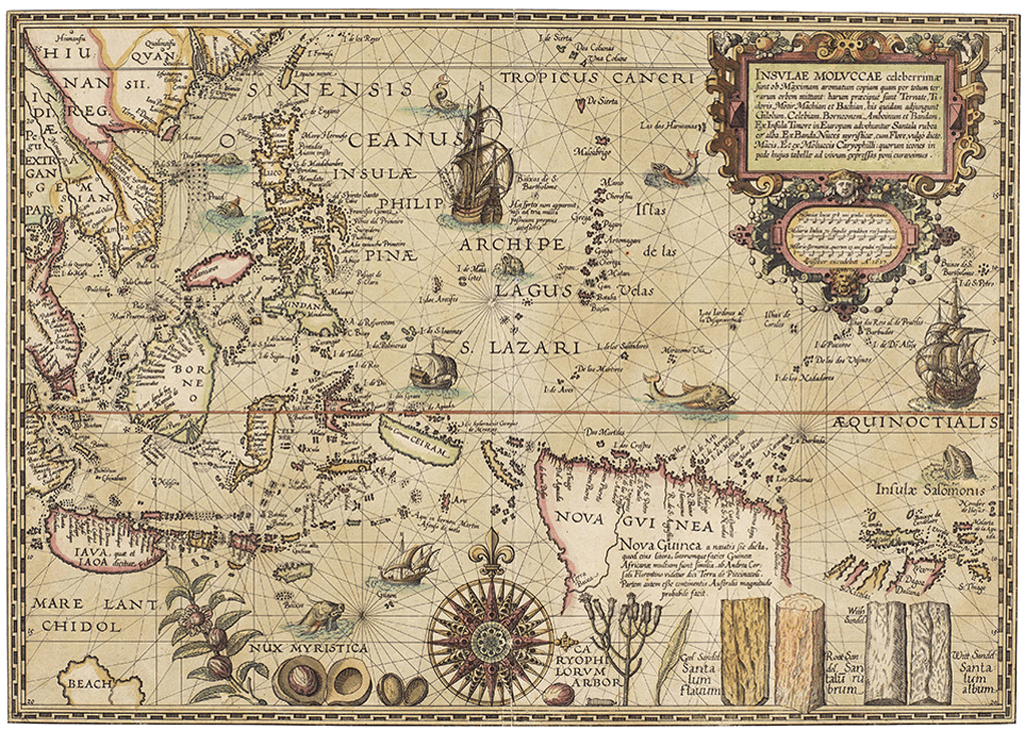

In the same way probably the most British dish you can eat is curry, as a result of the colonial heritage from the days of British Raj in India, the most Dutch thing you can eat is likely an Indonesian rijstaffel (see recipe below), thanks to the Netherlands’ long-term trade via the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (the VOC, or the Dutch East India Company) with the famed Spice Islands of the East (the Maluku or Molucca Islands). This small group of islands in the Molucca Sea, in the north-east of Indonesia between Sulawesi and Papua New Guinea, is the world’s largest producers of mace, cloves, nutmeg and pepper. As a result, Indonesian spices and flavours have long been familiar Dutch staples, including in the wonderful street varieties found in Amsterdam.

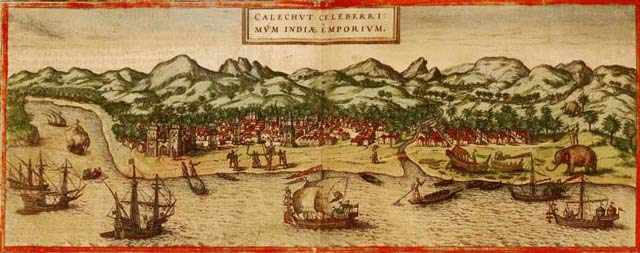

European trade with the Spice Islands began in 1512 after Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama discovered a sea route to India that connected the Indian and Atlantic oceans; before that, obtaining spices, Chinese silks, Indian cottons, Arabian coffee and African ivory was a costly and time-consuming affair, as these goods had to be shipped and then transported overland, passing through many traders’ hands before eventually reaching Venice – the chief point of trade contact between Europe and Asia – where their cost was up to 1,000% higher than the price originally paid for them in the Spice Islands.

You may wonder why the desire for such a small and unnecessary-seeming thing as the subtle, delicate flavourings and aromas of a certain spice or herbal ingredient would motivate our European forebears to undertake such long and arduous sea journeys to unknown lands, yet if you try removing all spices and herbs from your cooking, you’ll soon understand how valuable these indeed are.

Once you discover how much depth, texture, pungency and richness of taste these can add to your otherwise boring or bland-tasting food, your desire to repeat these sensations becomes very addictive, and you experience an intense craving for more of these amazing taste-sense experiences.

Therefore, an insatiable desire for these pungent ingredients is what drove the expeditions and travel of these brave, curious explorers, who succeeded in opening up new transcontinental maritime routes, ultimately paving the way for our modern globalised world and its complicated (and ecologically disastrous) supply chains.

Such demand led to many wars and acts of piracy between European and Asian nations as they fought to outdo each other in the race to claim ‘ownership’ of these exotic lands and their goods, thereby creating the ensuing horrors of slavery, exploitation of indigenous peoples, deforestation and ethnic wars caused by the disrespectful mapping of colonial conquerors, who simply drew up boundary lines willy-nilly to suit their own aims, which were utterly out of sync with tribal peoples’ boundaries.

Another factor in terms of what motivated this vastly lucrative, competitive and destructive trade is that, while spices and extra ingredients were hardly the stuff of necessity – you could still eat potatoes, vegetables and meat without them, as sadly the poor who could not afford them had to do – their very subtlety and unnecessariness is actually what made these goods so compelling (the spice equivalent of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’, if you will). The ownership and use of such luxuriously unnecessary spices became a distinct mark of social and economic ‘arrival’ for many of the ambitious VOC merchants’ families and the other wealthy patrons who could afford them.

Dutch still-paintings were all the rage

These spices were also deemed valuable because they derived from mysterious far-away lands, which their purchasers could boast of either visiting or financing expeditions to. Well-off hosts revelled in the one-upmanship of displaying their ostentatious wealth through hosting elaborate banquets. This desire to show off their exotic acquisitions in turn gave rise to the artistic trend that emerged during the Dutch Golden Age of depicting fruits, shells and flowers from these strange new lands in meticulously detailed and expertly crafted still lives, which became very fashionable at that time – the 17th century version of Instagram, if you will.

Another direct result of this demand for spices was the VOC’s creation of our now-familiar, but then-pioneering financing methods. The VOC was the world’s first corporation, and financing it relied on the purchase of stocks, joint stock corporations, investments in maritime insurance, futures trading, favourably (or unjustly) tilted trade negotiations and agreements, warfare, actual and financial acts of piracy, and (often violently) enforced monopolies. It was the first conglomerate, and the first company to be listed on international stock exchange – in effect, the beginning of capitalism as we know it.

“Exposure to new lands through travel and the sense-stirring revelations of heady new spices made our world what it is today. The demand for these far-flung fragrant spices and other exotic goods not only contributed to laying the foundations of today’s consumerist society, but also to all of the horrendous after-effects of colonialism and the global supply chain – the single-biggest driver of climate change”

It is probably no surprise, then, that the originally Dutch settlement of 1624 on the southern tip of the Hudson River, known then as Nieuw Amsterdam, eventually became Manhattan, New York – and the world’s leading exponent of capitalism.

Therefore, it was due to this exposure to new lands through travel and the sense-stirring revelations of heady new spices that made our world what it is today. The insatiable demand for these far-flung fragrant spices and other exotic goods not only contributed to laying the foundations of today’s consumerist society, but also to all of the horrendous after-effects of colonialism and the global supply chain – the single-biggest driver of climate change, the greatest existential threat mankind has ever known.

If you think about how we ‘commoners’ today enjoy goods from far-flung lands as everyday ingredients in our mass-produced food, you can see how the ‘trickle-down’ economic concept was expected to work; of course what you don’t see is all the dreadful exploitation, slavery, child labour, deforestation and devastation of resources going on in these countries now – but that is a topic for another blog.

Yet we would not recognise our modern life if we did not have what has now become daily access to commodities such as:

- chocolate (cacao – from South American and Asian rainforests);

- cinnamon (from Sri Lanka, India and Burma, also the West Indies and South America);

- garlic (China and Middle Asia [Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan; from there to Egypt]);

- pepper (India and Indonesia);

- sugar (originally, Papua New Guinea, then South East Asia, China, India, Haiti and Dominican Republic);

- turmeric (South East Asia and Pacific islands [Tahiti, Hawaii, Easter Island]);

- tea (China, then Japan and later India);

- ginger (India and China; throughout South East Asia);

- coffee (North Africa, originally; now South East Asia, Central and South America, predominantly);

- tobacco (originally South and North America; today, China, India, Brazil and the US are the top producers);

- vanilla (originally Mexico, now mostly Madagascar, Tahiti, Indonesia and Uganda);

- chilli and paprika (Mexico); and

- saffron – officially the world’s costliest spice by weight, it comes from the dried stigmas of a particular crocus flower, Crocus sativus (originally cultivated in Greece, now also cultivated in Iran, India and Morocco).

Amsterdam and the Netherlands – in all their spicy ‘glory’

They say if you like Amsterdam, you will love Europe; while every European city is different, it is true that, being a seafaring country and having both a Catholic and Protestant heritage – not to mention all those amazing canals, frequently superior in construction to their Venetian cousins – Amsterdam reflects some elements of nearly every European country.

Thanks to its early explorations of Asia, South America, Africa and the Caribbean during the Dutch Golden Age period of (particularly) the 17th century – and its colonial acquisitions in countries and islands such as Curaçao, Aruba, New Zealand Surinam, South Africa, Indonesia, Sint Maarten and Dutch Guiana, and parts of Australia, North America, Japan and India – Amsterdam has long had a tradition of open-mindedness, tolerance and outward-lookingness, especially towards other cultures and religions (not excluding its famously liberal attitudes towards sexuality – an altogether different form of spiciness! – as a more recent development).

In the late 1960s and 1970s, Dutch culture became a model of tolerance and leniency towards drug use, euthanasia, abortion/birth control, prostitution and homosexuality, with a globalised sex industry expanding beyond the red-light districts in Amsterdam and other Dutch cities (as I myself have experience of through outreach to prostitutes from Santo Domingo and other colonial outposts, as I explain later). However, the influence of a heavily judgemental Calvinistic streak has also left its mark on the psyche of the nation; even if 82% of Dutch people no longer believe in God or attend church these days, they still adhere to the virtues of integrity, truthfulness, hard work, respectfulness, reliability, acceptance, self-discipline and efficiency that derive from a heavily Calvinistic background.

For those who do not know, John Calvin was a highly influential theologian and preacher of the Reformation movement that swept Europe in the mid-16th century as a result of the teachings of German Martin Luther, which emphasised a personal faith through one’s own reading and interpretation of the scriptures. Later, the French-Swiss Catholic-turned-Protestant John Calvin became a leading proponent of Protestantism, and his teachings were eagerly embraced by the Dutch people – including then-leader William of Orange, as well as a large percentage of commoners.

Prior to the Reformation, all of Europe was Catholic, and therefore under rule from Rome. However, there were also many inter-national economic rivalries and wars – such as the Eighty Years’ War between Spain (under Philip II) and the Netherlands. This war came about as Spanish Catholics began a campaign of harsh persecutions against Dutch Calvinists, which led to resentment and resistance via a wave of rebellious, disorderly attacks known as the Beeldenstorm (image storm) of 1566, in which Catholic images and statues were destroyed. Inevitably, the Dutch broke free from Spain in 1581 and formed the Dutch Republic. One wonders what the world might have been like were it not for Calvin’s preaching!

The Dutch rebellion against Catholic and Spanish rule also ignited their determination to overthrow the monopoly of the spice trade and send their own ships east, thus forgoing the necessity of trading with Spain and Portugal. The Dutch soon became the leading maritime explorers of the 17th century, thanks in part to the fleet construction of their East Indiaman ships, which were lighter and more compactly built than the heavy Portuguese and Spanish war ships (they were also initially faster than other European ships, however, as the British began to use copper sheathing in the construction of their ships’ hulls, their speed eventually overtook the Dutch, who delayed using this innovation for various reasons).

The Dutch are certainly some of the world’s most incredibly ingenious, hard-working, tenacious and resourceful peoples – for example, their advanced abilities to reclaim land from the sea using dikes and polders is an amazing feat of engineering. After the catastrophic North Sea flood of 1287 (aka ‘St Lucia’s Flood’ – considered one of the worst floods in history), which killed 50,000 people and destroyed the many small earth-mound villages protected by dikes at the time, the Dutch had to work extra hard to push back the newly formed Zuiderzee (‘South sea’) created by this flood. They slowly pushed back the Zuiderzee by building newer, stronger dikes and creating polders (land reclaimed from the sea through draining water using canals and pumps, which were then maintained to keep the land dry and prevent further flooding). This ingenuity has given rise to the proverb, ‘While God created the Earth, the Dutch created the Netherlands’.

The Dutch are also master linguists; while their own language is incredibly difficult for any non-native to pronounce correctly or master, they seem to make up for that by mastering everyone else’s language, so if you but open your mouth to speak – even if you are trying really hard to learn and practise speaking Dutch – they will immediately discern your language and start communicating with you in it instead. Whether this is because they are proud of their seemingly almost supernatural gift for this, or embarrassed that their own language is so difficult and contains so many challenging sounds, is hard to say. (Dutch is actually the closest linguistic relative to English, specifically the version (Frisian) spoken in its most westerly area – Friesland, or the Frisian Islands. The Frisii (Frisians) were the first tribe to settle the Netherlands in 400 BC.)

It was also largely in part due to French-Dutch explorer François Caron’s mastery of Japanese (one of the factors in my novel) and other languages that the Dutch ended up having a trading monopoly in Japan – which goes to show how essential language skills are to the evolving development of international trade and diplomacy.

Chiaroscuro: my personal history lessons in Amsterdam

I lived in Amsterdam (or A’dam, as we called it) for a brief two years during my early 20s, during which time I worked in the fundraising and communications office of Jeugdt Met Een Opdracht (Youth With A Mission, an international, interdenominational Christian missionary and relief organisation, which I had previously trained and travelled with in Latin America before I felt specifically compelled to come to Europe). YWAM’s Amsterdam HQ – situated in a large building opposite Amsterdam’s Centraal Station (main train station), which proclaimed ‘God Roept U’ (God Loves You) from its top storey – was set up by The Father Heart of God writer Floyd McClung, Jr. and other former hippie-trailsters-turned-Christian-evangelists who had previously used two disused house boats (known collectively as ‘The Ark’) as a base for outreach to the city’s large drug-using/abusing community, and to scores of disillusioned young people asking deep questions about the meaning of life.

By the time I joined YWAM in A’dam, it had attracted a fairly large corps of international volunteers, most of whom either lived in shared temporary communal housing or in flats in various parts of the city (I lived for a time in the Bijlmermeer – at that time, a cheap but very rough neighbourhood, considered a Dutch ghetto – and afterwards in the outlying provincial [and then rather boring, though much safer] village of Purmerend).

While my ‘day job’ was all about boosting funding through producing a newsletter for the ‘Friends of Amsterdam’ and recording various audio-visual productions, I spent much of my spare time doing outreach to the (mostly) Spanish-speaking prostitutes in De Wallen, Amsterdam’s Red-Light District. This is one of the reasons why, despite my efforts to practise and learn Dutch properly in the two years I lived there, I could never master it – instead, my daily language ended up being a very weird kind of ‘Danglish’ (Dutch-Spanish-English) hybrid; for some reason, I also developed another weird habit of speaking in a form of transliterated English whenever I find myself in any situation where I feel like a foreigner – which I still do occasionally even now!

Amsterdam’s infamous De Wallen (red-light district)

During my time in A’dam, I experienced much of the sharp moral and other contrasts of its inhabitants, witnessing at first hand their inherently Calvinistic qualities and simultaneous liberal attitudes. Such ambiguity (hypocrisy?) was possibly a contributing factor in my personal experiences of spiritual abuse at the hands of YWAM Amsterdam’s leadership, as while seeming to be forward-thinking and open, and emphasising compassion, it was in fact controlling, legalistic, dismissive and misogynistic (after submitting something I’d been asked to write that displayed my command of vocabulary and contested the viewpoints of the main leader, I was criticised for being a ‘dangerous female intellectual’ and asked to leave the organisation – an event that subsequently caused me to stumble in my faith for several decades after [and which I can only recently claim to be healed of]).

Yet as I also witnessed some very powerful and dramatic spiritual confrontations between the powers of darkness and the power of light during various street-outreach sessions, I will forever associate Amsterdam with the concept of chiaroscuro – the technique of highlighting contrasts between dark and light, which Rembrandt and other Dutch Golden Age masters are famous for.

Despite the above negative experience and my fruitless efforts to acquire the Dutch language, those two years in Amsterdam changed my life immensely – for the better, mainly. I developed a more European (and truly cosmopolitan) view of life, and became very aware of (and deeply ashamed by) the US’s war-mongering footprint across the globe through understanding how this was perceived by other nations. While generally kind-natured, the Dutch are also typically very blunt, and do speak their minds; it took me a while not to take it personally if they criticised US foreign policy whenever I opened my mouth, though this certainly made me determined to develop a stronger Irish accent so I no longer felt obliged to apologise every time I opened my mouth!

By the time I returned to the US, I no longer considered myself American – the insular, imperialistic values the US manifested seemed completely out of sync with a more tolerant, globally aware and objective European vantage point. I felt like a stranger, a permanent exile (or expatriate), which led me to return to Ireland to study, and thence to my marriage and relocation to London.

I had also become used to the Dutch way of life – cycling to the shops each morning to fetch a bouquet of fresh tulips from the market, along with my food for the day (typically, some broodje [bread], kaas [cheese, usually Gouda], jam and koffee for breakfast and lunch, with the makings for a savoury pannekoeken [pancake], a rijstaffel, curry or vegetarian stir-fry for dinner).

I particularly loved the street snack of frites met sate (chips or French fries with spicy Indonesian satay sauce), available from many street vendors around the city, and the wonderful stroopwaffelen (two waffle biscuits or cookies cemented with a thick caramel-like syrup). I also learned to love (and still crave) the Dutch dubbel zoute (or double salted) liquorice, though even many Dutch people can’t take its strong flavour! I was thrilled to discover you can get a gluten-free version of this at London’s Borough Market.

As for raw herring – just… no! That was simply one cultural adaptation too far!

I am grateful for very fond memories of some lovely Dutch people I knew from that time, such as Peter and Marilyn Gruschka, who always demonstrated the most exemplary hospitality, fun and fellowship on their colourful houseboat, and other international friends I made during that time – some of whom I am still close to (or have renewed contact with, thanks to Facebook).

I am also deeply grateful for the many long hours I spent at the Rijksmuseum, admiring and sketching from the works of the Dutch Golden Age painters – Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, Jacob van Ruisdael, Aelbert Cuyp, Pieter de Hooch, Adriaen van Ostade, Jan Steen, Nicholas Maes, Frans Hals and many others. This has made me a lifelong, devoted fan of this period of time, particularly of the genius of Rembrandt.

I finally went back to Amsterdam for the 2015 Amsterdam Salsa Festival, and was delighted to revisit a few favourite haunts – the Oude Kerk, the Van Gogh Museum, the Stedelijk Museum, Leidseplein and Rembrandtplein, Dam Square, the Concertgebouw, the Rijksmuseum and Vondel Park – and enjoy some of my favourite street food. I even visited Jeugdt Met Een Opdracht’s HQ, and believe that was a good step towards being able to leave the remaining spiritual dark shadows cast on me from that time in the past, where they truly belong.

The Rijksmuseum

Being that we are unlikely to be able to travel any time soon (even short-haul, as in to Amsterdam), all this talk of far-flung spices has whetted my appetite – both for revisiting (mentally) many of the wonderful places I have traveled to or lived in, and the crave-inducing foods I savoured on these trips. So I hope to write a few more shorter travel-and-food blogs along this vein, but this will do for now. Meanwhile, I will leave you (and end this blog, finally) with the background about and a few recipes for creating a traditional Dutch-Indonesian rijstaffel. I intend to make this for a New Year’s treat – though I will hardly need to cook a whole rice ‘mountain’ just for two!

The famous Dutch-Indonesian Rijstaffel

The traditional Dutch-Indonesian rijstaffel (literally, ‘rice table’)was modelled on the Indonesian custom of serving a ritual feast, called a ‘selamantan’, which featured a variety of dishes surrounding a cone-shaped, turmeric-seasoned rice ‘mountain’ to represent the metaphysical Hindu Mount Meru – the sacred five-peaked mountain of Hindu, Jain and Buddhist cosmologies. The selamantan (and consequently the rijstaffel) was an elaborate spread of 11–21 dishes (always an uneven number, as even numbers were seen as somewhat inauspicious), served with various condiments and a literal mountain of rice.

One of the reasons the rijstaffel became so popular with the Dutch is that it offered the wealthy merchants and VOC colonists a way to sample and balance a range of exotic flavours and consistencies (salty, sweet, crunchy, smooth), and to show off all their spicy and exotic acquisitions to their friends and the business associates they wished to impress.

Below are a select few recipes for some of the more memorable dishes of the rijstaffel – once you get used to these wonderfully pungent and aromatic flavours, you’ll understand why the Dutch developed such an addictive craving for the exotic flavours of the Spice Islands that they outdid every other nation in dominating the East Indian trade – or at least I do! I’ll start with my favourite sauce in the whole world, Gado Gado – this crunchy spicy peanut sauce would certainly make me endure months at sea and travel halfway around the world, although obviously that isn’t necessary now.

Gado Gado

1 small onion, chopped

3 cloves garlic, minced

2 teaspoons ground coriander seed

1 teaspoon ground cumin seed

1 tablespoon dark-brown sugar

1–2 teaspoons sambal ulek (a spicy Indonesian pepper paste, found in the world foods aisles of many supermarkets)

2 tablespoons kecap manis (a thick, sweet soy sauce found in Asian food stores)

2 tablespoons rice-wine vinegar

1 1/2 cups smooth or crunchy peanut butter (according to taste)

1 tin of coconut milk

chopped peanuts, as a garnish

Fry the onion, garlic, coriander and cumin in a little oil until the onion is soft. Add the sugar, kecap, vinegar and sambal, and stir until combined. Now add the peanut butter to make a thick paste. Slowly stir in the coconut milk and combine with the peanut-butter mixture, continuing to whisk the ingredients together.

Once the sauce is smooth, let it simmer on a low flame for about 10 minutes, remembering to keep stirring to keep it from burning. Thin with water or broth as needed, and then serve warm with salad, chopped raw or cooked vegetables, beancurd and egg. For grilled chicken, pork, fish or seafood kebab skewers, use the variant known as sate or satay* [see below for an easy recipe] – both versions go well with everything, and are great with chips (in Amsterdam, ask for ‘Frites met sate’ from a street vendor).

As a final touch/for extra crunch, add a few chopped peanuts as a garnish.

*Sate [or satay] sauce

1/2 lime, juiced

1 tsp honey

1 tbsp soy sauce (I use the gluten-free variety)

1 tbsp curry powder

3 tbsp peanut butter (smooth is best for this version)

165 ml coconut milk

Mix the first five ingredients in a bowl, blending well, then transfer to a small cooking pan. Gently pour in the coconut milk and heat, stirring continuously. Simmer for 5 minutes and serve.

Ajam Kecap (Chicken with Ginger and Soy Sauce)

900g chicken meat (preferably thighs; can use breasts)

4 tablespoons vegetable or coconut oil

2 large onions, chopped

3 cloves garlic, minced

3–4 tablespoons chopped fresh ginger root

2 tablespoons ground ginger

4 tablespoons kecap manis

2 tablespoons rice-wine vinegar

1 teaspoon sambal ulek

1/2 cups chopped crystallised ginger

Cut the chicken into one-inch pieces. Season the meat well with salt, pepper and two tablespoons of the ground ginger. Heat the oil and fry the chicken pieces until they begin to brown. Add the onion, garlic and ginger root. Cook until the onion softens, then add the kecap, vinegar and crystallised ginger pieces. Cover the pan and simmer on low heat for about 40 minutes.

For an alternative version with pork (known as babi kecap), substitute 900g of cubed pork; or for a vegetarian version, you could perhaps try tofu as a substitute.

Serundeng (Coconut Peanut Topping)

1 to 2 tablespoons coconut oil

1 medium onion, finely chopped

2 cloves garlic, minced

1-inch piece of ginger root, peeled and grated

1 teaspoon ground cumin seed

1/2 teaspoon ground coriander seed

1 tablespoon dark brown sugar

Juice of 1 lime

11/2 cups dried unsweetened shredded coconut

1 cup roasted salted peanuts

Salt to taste

In a large non-stick frying pan, fry the onion, garlic and ginger root in the oil until they are soft and fragrant. Add the dry spices and the brown sugar and continue to cook, so the sugar dissolves. Add the lime juice and 1/2 teaspoon of salt. Add the coconut and continue to cook, stirring all the time until the coconut has absorbed all the seasonings and is toasted and dry. (You can do this last step by spreading the mixture on a baking sheet and baking it in the oven. The coconut should be dry and golden; make sure it does not burn).

Last, add the peanuts and toss to blend. Serve this over rice, or over anything with peanut sauce.

Cook’s note: Serundeng is a condiment served with rijsttafel. It is like an Indian dry chutney, something to sprinkle over rice or vegetables. Its sweetness will balance out the heat from spicy dishes.

Udang Kuning (Shrimp in Turmeric Sauce)

Note: You can prepare the spicy paste ahead of time, and lightly sauté the shrimp in the sauce just before you are ready to serve it.

1 tin coconut milk

2 djeruk purut (lime leaves; only use them fresh)

Juice of 1 fresh lime

Basil or coriander leaves for serving

450g raw shrimp, peeled and deveined

For the spicy paste:

1 medium onion

3 cloves garlic

1 teaspoon coriander seed

2 stalks of fresh lemongrass, inner white part only

2 inches fresh ginger root, chopped

1 tomato

1 teaspoon sambal ulek, or 1 fresh serrano or chili pepper

1 teaspoon turmeric powder

1 teaspoon salt

Chop all ingredients for the spice paste and blend them together in a food processor until smooth. Heat a little oil in a heavy saucepan and fry the spice paste for a few minutes, until it gives off a strong, fragrant aroma.

Then add the coconut milk and the lime leaves, and simmer on low heat for about 30 minutes. Strain the cooked mixture, squeezing the solids to extract the flavour. Add the lime juice for extra flavour. Before serving, lightly sauté the raw shrimp in the sauce until cooked through.

*Note: Most of these recipes have been adapted for UK shoppers and to suit my personal gluten-free needs, but derive from Josephine Nieuwenhuis’s blog on rijstaffel – please see her blog for the full-gluten, US version.

Thanks Jane what a wealth of research and recipes! Yes ‘research rabbit holes’ always a danger, although fascinating.

LikeLike

Yes indeed! Am trying to keep all my research notes in some form of order – considering trying Scrivener, have you used it yet? – and allow them to inform the story without overtaking it.

LikeLike

Hello! I just stumbled upon this post searching for friends of my mum – Peter Gruschka and Marilyn – do you by any chance have an address or contact details for me? Or hints as to where I could find them? I will be in Amsterdam for the next three days and if I could find them, that would be so great and your help immensely appreciated. My mum and them used to work and live together on a houseboat in the 70s. I can give you more private info through email or by phone.

I hope to hear from you! Thank you!

Greetings from Vienna, Austria

Melissa

LikeLike

Hello Melissa,

I really wish I could help you as I too would love to know the whereabouts of Peter and Marilyn Gruschka, who I remember very fondly from the years I lived in Amsterdam while serving with Youth With A Mission. I don’t really know why it did not occur to me to look for them myself the past two times I’ve been in A’dam as I too would love to see them, only that that was a very long time ago (mid 1980s) when I used to visit them on their houseboat, and I could not remember which canal it was on. I do have one mutual friend in Canada I am still in contact with from that time who might be able to help – I will message her via Facebook today and see if she has any info for me. Meanwhile, please feel free to message me on jane.cahane@gmail.com / Whatsapp +44 7899 757400. If you do find them, I would be so grateful if you would give them my love and greetings and tell them I am asking for them! (Oh, and btw, I did delete the rest of your name from your post; hope that worked!)

LikeLike

Enjoyed scrolling (albeit quickly) through your comments. Having lost touch with Peter, I was googling “Peter Gruschka,” when I came upon your site. Peter and Marilyn were indeed dear. I met Peter in Afghanistan when there with Floyd, and then was on the Ark when Marilyn first came as a rank unbeliever. I was in Aʻdam for c. 2 years before moving on to Nottingham to help out with the Nottingham fellowship that had sprung up through John Goodfellowʻs inspiring life.

Those Dutch are indeed a joy to behold, even as their bluntness is not always so enjoyable to the non-Dutch. I myself would not call the Europeans any more “objective” than Americans; they have their own form of subjective worldview. That said, I too enjoy the European flavor, and today keep up my Europe-contact. I always say, “I love America; I just donʻt want to be here all the time.” (but that is a privilege that many Americans–as opposed to Europeans–simply donʻt have, separated from East and West as we are by two large oceans.)

All power to your novel writing… novel as it is for you!

Paul

LikeLike

Awesome bloog you have here

LikeLike

Hey again! Sorry, I made a mistake by letting autofill fill in the form – can you please delete the post where it shows my full name – asking for your help to find Peter Gruschka? Thank you!

LikeLike