‘Weeping endures for a night, but joy comes in the morning’… ‘You turned my mourning into dancing; you removed my sackcloth and clothed me with joy’ (Psalm 30, verses 5 and 11)

The great 20th-century Christian apologist, writer and Oxford don CS Lewis wrote a book called Surprised by Joy — an autobiography detailing his spiritual journey from atheism to a profound Christian faith. In it, he described how, as a young man, he had been tantalised by a brief experience of something he could only describe as ‘joy’, leading to a lifelong search to discover the source of this intense, Sehnsucht–like longing, desire or yearning. Ironically — perhaps — as a certified bachelor, Lewis was later surprised by falling very deeply in love with a fellow writer and poet named (Helen) Joy Davidman, a young, divorced American Jewish convert to Christianity whom he initially married purely to enable her to relocate to England.

Tragically, four years after they wed, Joy died of cancer at the tender age of 45. Despite a few brief years of remission that allowed them to develop a greatly happy and fulfilling marriage — as much a meeting of minds as a union of bodies — God did not answer further fervent prayers for healing. This loss, as unexpected as him finding love, severely rocked Lewis’s faith. Despite the fact he had written apologetic discourses on suffering (The Problem of Pain) and was aware this joy he had sought was something ‘other’ beyond this earthly life, so not to be confused with mere mortal happiness, it perplexed Lewis deeply that a loving God had given him such a profound earthly happiness only to cruelly snatch it away. He later wrote about his personal grief journey with heart-breaking honesty in A Grief Observed.

The proving (testing) of Lewis’s faith through these life events is very much a testament to the fact that even though we may believe in and love God with all our hearts, souls, minds and strength, we are still not exempt from pain and suffering, which, when it experienced, make this life seem utterly barren, absurd and devoid of meaning. As much as death is the opposite of life, grief appears to be the opposite of joy.

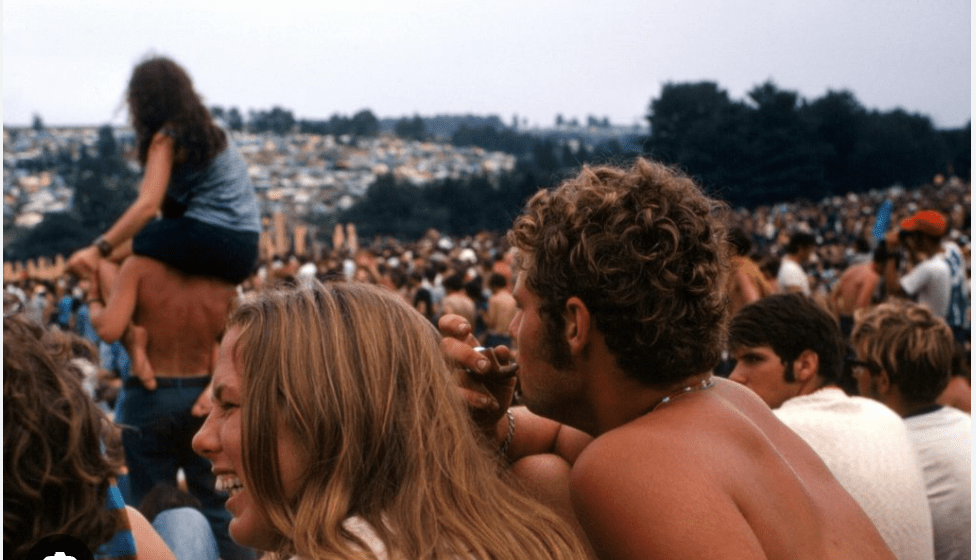

However, I use the word ‘appears’ intentionally, for Lewis’s earlier search for joy and Platonic leanings also prove — in the most profoundly existential way — that true joy is something ‘other’ than earthly happiness. For the chief problem with earthly happiness is that it can and does eventually fail, fade or die. Indeed, by ‘law’ it is bound to do so, in much the same way as the law of gravity works — eg, whatever you throw up will come down — or, say, the second law of thermodynamics works (eg, all systems tend towards decay), when applied to any earthly being or even any political, humanist, romantic or religious entity, whether a human love affair or humanistic movement, eg the Hippie Movement of the late 1960s/early 1970s. Sooner or later, these things will all come to naught, largely because their essence is temporal.

So, is there any real hope for joy in this life, or are we all doomed to futility in our search for it? And what, in fact, is joy — if there is indeed such a thing as true joy?

Ancient and contemporary perspectives: mankind’s quest for joy

In many ways, my own spiritual journey and faith crises due to grief and multiple losses — eg jobs, vocations, children, divorce, bereavement, identity, a sense of home and/or belonging, and not a few unfulfilled dreams and/or unrequited romantic dreams (in the broader sense of the word; see CS Lewis’s helpful list of seven forms of Romanticism in the preface to The Pilgrim’s Regress*) — mirrors Lewis’s. However, as much as his accounts of his personal spiritual struggles and learnings resonate with me and no doubt millions of others, they are far from being the only reason I have related so profoundly to to his unique mind ever since I first discovered him in my early 20s.

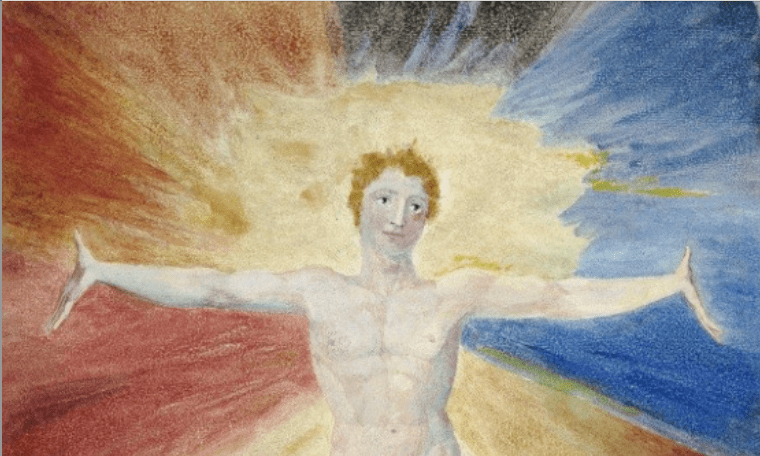

As an example, in one of my earliest spiritual moments, which occurred around the time I was conducting what I considered a highly rational, means-tested, critical-thinking approach to a search for faith in God out of a place of existentialist near-atheism, was a sudden, profound insight that came to me as ‘the soul is of longing, but the spirt is of fulfilment’. In other words, while Sehnsucht is the expression of a soulical longing or desire for fulfilment, it can never be truly fulfilled without the spirit. That is not to say we can’t experience profound happiness, a sense of fulfilment, and moments of true joy and rapture in life, but that for true fulfilment, all our soul’s (mind, will, emotions) longings must be augmented by the extra-dimensional aspect of spirit. And by spirit, I mean that spark by which we are all united (or not) with the eternal (meaning Spirit, God, our Creator, the divine).

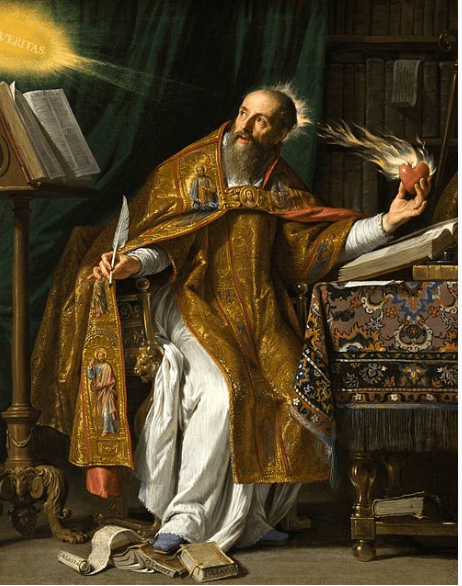

At the time I received this insight, I had been studying the writings of various poets, philosophers and theologians — from ancient Greek/early Roman (eg Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Epicurus, Philo, St Augustine), to early mediaeval–Renaissance–Reformation (St Anselm of Canterbury, Boethius, St Thomas Aquinas, Dante, Eriugena, Machiavelli, Omar Kháyyám, Abelard, St Francis of Assisi, Sir Thomas More, Erasmus, Pico della Mirandola), and to early modern era to the contemporary period (Descartes, Hobbes, Locke, Grotius, Montaigne, Pascal, Voltaire, Hume, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Kant, Edmund Burke, Hegel, Henry David Thoreau, William James, Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, Kierkegaard, Jean-Paul Sartre, Camus, AJ Ayer, Nietzsche) — in addition to my other BA courses (art history, literature, cosmology, languages).

As a result, my mind was a swirl of philosophical, scientific and theological questions. I had also read sections of the Koran, books on the Tao Te Ching and the Baghavad Gita before I finally sat down in the woods, alone, to read the Bible with an open mind, asking God to reveal himself to me if He was real and applying all my literary criticism training to the Word (I urge everyone to do this, as that is what did eventually persuade me that both the old and new testaments have one overarching Author, whose voice I began to hear quite clearly for myself after some time — something I never experienced reading other spiritual holy books, despite these also containing great wisdom and insights).

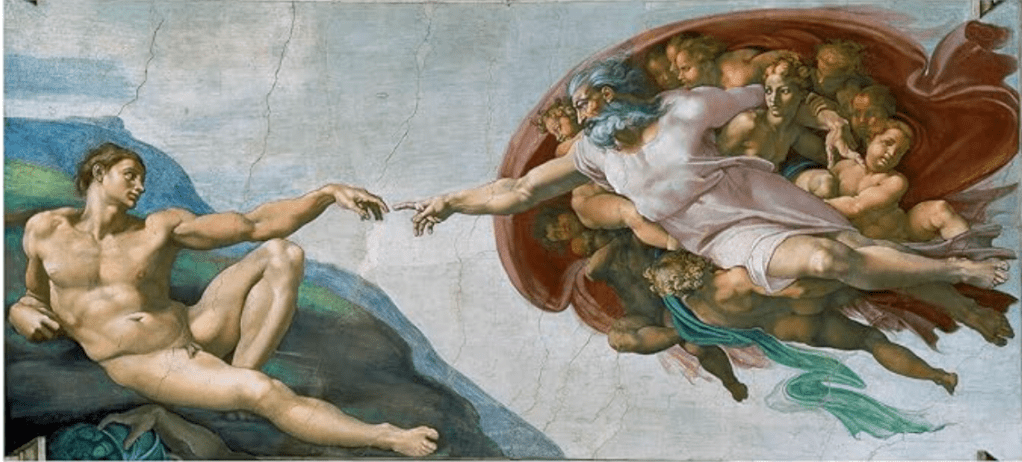

Amid this spiritual quest, I was also, as a creative person, looking at all the highest achievements of humankind in the arts, and reflecting on what these expressions of the soul revealed. I began to see how much all art, music, literature, architecture, science, philosophy — actually, every earthly form of creativity — expresses this Sehnsucht or deep longing for an earthly fulfilment of mankind’s greatest desires for a lost Eden, a humanistic Utopia or a perfect romantic union. Yet in nearly all these examples, there appears to be a gap where something vital is missing, as perfectly symbolised by Michelangelo’s famous painting of God and Adam in the Sistine Chapel, where there is a gap where their hands fail to touch.

As humans, we all receive that divine spark from our Creator; our mission on earth (should we accept it, haha) is to find and fill that gap. Or, as that other great 4th century theologian and philosopher, St Augustine of Hippo, put it, ‘You have made us for yourself, and our souls are restless until they find their rest in you, Lord’, ‘To fall in love with God is the greatest romance; to seek him, the greatest adventure; to find him, the greatest achievement’ (Confessions]).

I believe this is the essential meaning of Friedrich Schiller’s poem “Ode to Joy’”, set to rapturous music by Ludwig von Beethoven, and Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring”: all of mankind’s artistic endeavours are really a search for God, for a revelation of the infinite Other, which can only be found in true spiritual union with God. (On a side note, the etymology of the word ‘holy’ in English derives from Proto-Germanic hailaz, meaning ‘healthy, whole’.)

Therefore, I conclude that any discussion of or meditation on joy must also consider the distinctions between earthly, temporal joys and spiritual — and thereby eternal — joy.

Temporal (soulical) joys vs eternal (spiritual) joy

There are many things in life that can give us tremendous earthly happiness, fulfilment and joy. For most people, a happy marriage, a comfortable family life and healthy children are the main things that provide happiness and a sense of fulfilment. We tend to idealise those blessed with such gifts as having the ‘perfect’ life, although this may not mean they do, as even the happiest marriages and families may have their own secret trials and sorrows. It also does not mean that those who do not have a satisfying mate, children, living parents, a functional biological family or even a home to call their own do not have other blessings to make up for such perceived ‘lacks’ — they may thrive through being an active member of a church or other community group, having a pet(s), a network of close friends, varied interests and hobbies, or a life filled with adventure.

Other things, too, can provide us with earthly joys: participating in cultural customs and rituals and celebrations that reaffirm a sense of ethnic or national identity; having an exciting or rewarding job, subject of study or vocation; the sense of teamwork and collective purpose from engaging in an important or dangerous mission, eg war, civic protest, relief work, etc; enjoying creative play and then developing the skills and ideas to achieve artistic excellence; participating in dynamic sporting or other live events, eg rock-music concerts; even simple, literally earthly, pleasures such as cooking, hiking, gardening, fishing or birdwatching, where we can feel close to nature in an organic way.

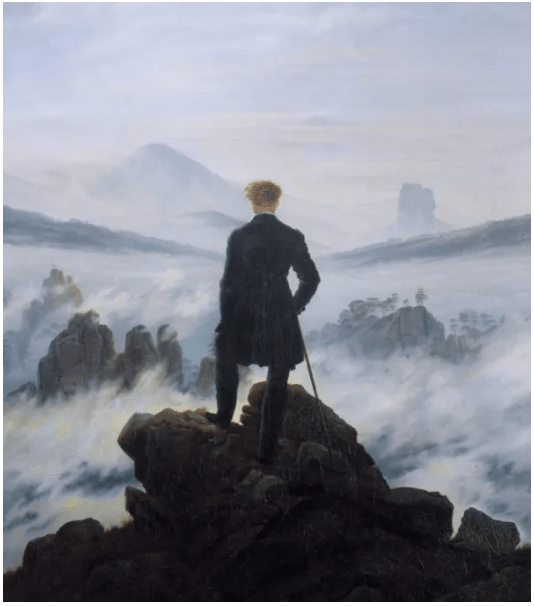

I think, for example, of that thrilling moment in the film Chariots of Fire when athlete and eventual missionary Eric Liddell wins the Olympic race, the sheer overwhelming joy of running poring through every frame. As he said, ‘God made me fast. And when I run, I feel His pleasure.’ His sentiments are certainly true for me — no doubt as well as for countless other salsa or other kinds of dancers, whether professional or purely social dancers — for I know without a doubt that God made me a dancer, it is one of the gifts He has given me, so truly I am filled with joy when I am dancing, especially whenever I have a great dance with someone where we as individual dancers and the music form a perfect ’trinity’ of flow, of connection. That is certainly one of life’s great ’free highs’ for me, as is the wonderful exhilaration of hiking up a steep summit or path and finally reaching the top/end where you can look out over the land spread out before you and realise how far you’ve come. As well as a literal pleasure, it is also a perfect metaphor for achievement, for spiritual and other journeys, and for personal growth.

The thing with all these earthly joys is that they help us to feel vitally connected, not only with other humans or ancestral traditions, but also with something deep inside us — our spirits, if you will. But we must always bear in mind with any earthly joys that they are by nature transitory. Families, marriages, romances, jobs, careers, creative successes, health, pets, financial or even national security can all be subject to what Shakespeare described as ‘the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune’ (Hamlet, Act III, Scene I). Then what happens when we lose these vital connections to others or even to ourselves? If our souls are crushed and our spirits dimmed through grief or loss of any kind, how can we reconnect and find meaning? Recover that spark that ignites true spiritual joy?

As Lewis’s story — and perhaps our own experience of grief or loss — tells us, the absence of those things that constitute our earthly security and happiness may cause us to doubt the goodness of God, the provider and source of all good. Like Lewis, we may also be rocked when the foundations of our sense of wellbeing, identity and self-esteem are destroyed; we may then feel adrift, bereft, purposeless, faithless, meaningless. As a result, we may become vulnerable, all to prone to throwing ourselves into mindless addictions — TV, social media, drink and drugs, overeating, overworking, overspending, etc — to numb the pain of our losses. We may despair of ever finding hope, joy, love, purpose, meaning or connection again.

It is at such times that we are most spiritually vulnerable, and at such times our spirit (inner man) most deeply needs to be reunited with God, ‘the author [originator] and perfecter [completer, finisher] of our faith’ (Hebrews 12:2). Because if we are wise, we realise that indeed, all earthly things we put our hope and security in can and will be shaken. Anything we love and that gives us joy and happiness is sadly, like our mortal bodies and the creation itself, subject to death and decay; we can lose them unexpectedly any day, and suddenly all those things we might have taken for granted — such as our homes, freedoms, rights and democracy — can be lost or taken away from us. And as for any earthly utopia, system or revolutionary movement, one only needs to study history to realise that these, too, seem doomed never to last.

This may fill us with despair, and yet if we turn to God, we find a remedy in His promises. For example, God says, ‘For the mountains may be removed and the hills be removed, but my steadfast love shall not depart from you, nor shall my covenant of peace be removed’ (Isaiah 54:10). Therefore, if we are in Christ, we can know Him as our inner anchor and our rock that will never fail us, no matter what happens in the external world or in our outer circumstances. These are not the basis of our identity, once we have surrendered our lives to God and become new creations.

This is the true meaning of faith, and why it is different from mere hope, because ‘Faith is the substance [foundation, tangible reality] of things hoped for, the evidence of things unseen’ (Hebrews 11:1).

Transcendental (non-earthly or spiritual) joy

I’d like to take a moment now to recount a recent story that is in fact the reason I felt prompted to write this meditation about joy.

As I’ve shared previously, I’ve been on my own personal and spiritual-growth journey with bereavement since losing both my father and husband last year. I’ve had to learn to slow down, take time to allow my body, mind, soul and spirit time to recover, and to experience what’s been referred to as the ‘seesaw of grief’ (from the course on The Bereavement Journey), whereby a mourner oscillates from periods of deep grief, sadness and loss to a place of being able, finally, to move forward and engage with life again, even if still carrying the lost loved one inside our hearts. So that is what I have been doing, just trying to restore my own rhythms, recover or discover what ‘the new normal’ means for me, while also trying to explore new things (eg tango lessons, travelling with a group, etc).

However, last Sunday, while en route to visit my husband’s grave before spontaneously deciding to drive all the way down to Eastbourne, Sussex, UK to see a replica of Magellan’s first round-the-world ship, the Nao Victoria — an exciting adventure in itself — I was listening to and singing along with some worship songs livestreamed from my church (Kings Church High Wycombe) when another worship song suddenly came on. And as I began singing along with the words of this song (“I Know Who Holds Tomorrow” , which went something like, “Many things about tomorrow/I don’t seem to understand/but I know who holds the future/and I know who holds my hand.”

As I sang these lyrics, I suddenly had a tremendous release of spiritual (or Holy Spirit) joy that manifested in me erupting into pure, childlike laughter, which flowed from the very centre of my being. Now I was nowhere near feeling any kind of earthly joy or happiness at that moment, so this was certainly something ‘other’ — from another dimension. While I have had a few brief moments like that in my past experiences of worship, this was entirely unique, especially as it lasted for a good 20–25 minutes.

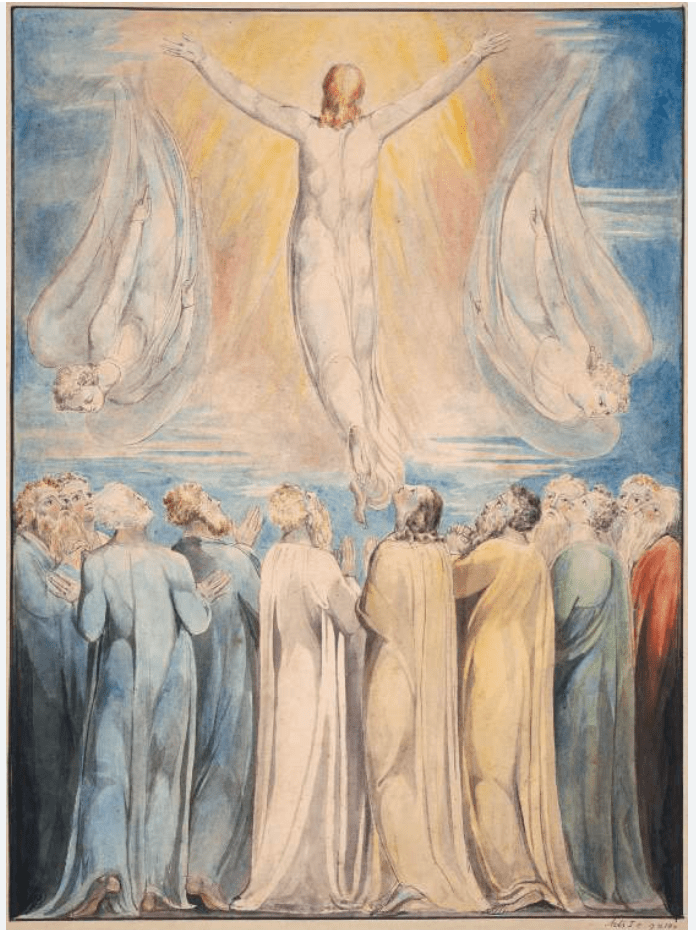

In my mind’s eye, what I saw was that amid a nuclear explosion consuming the Earth and everything suddenly being blown to smithereens, as is described in the New Testament (“But the day of the Lord will come like a thief. The heavens will disappear with a roar; the elements will be destroyed by fire, and the Earth and everything in it will be laid bare” [2 Peter 3;10]), and then Jesus appears and everything — all this waste, suffering and destruction — is completely consumed by the even greater light of His presence and love. Having just been reading the news and worrying about the possibility of World War III taking place following the US attack on Iran, this was much on my mind.

Now, you might think it’s weird that I would be filled with laughter at such a picture; also, tbh, I don’t normally give much time of day to what eschatologists say or like to argue about the supposed ‘The Rapture’ (the Second Coming of Christ), as I’ve always been theologically on the side of needing to be prepared for not having a supreme ‘Deux ex machina’ event to save us from a destruction we have so wilfully brought on ourselves. However, what made me laugh and be so suddenly and truly filled with what I can only describe as an abundant outpouring of pure Holy Spirit joy was that I could hear Jesus’ words at that very moment, not aloud but deep in my spirit, saying: “When all these things begin to happen, stand and LOOK UP for your redemption is drawing near!”

It was this — the command to look up and away from earthly worries, joys, fears and concerns, and see God, in the person of His Son, Jesus — that filled me with laughter (as in a sense of ultimate freedom) and, dare I say it, a sense of pure, unadulterated, bliss and ‘rapture’. Frankly, until this moment, I had never understood why the Second Coming of Christ has always been called this, but now, indeed, I do know and understand it!

I spoke before about how all mankind’s longings as expressed in art over millennia were all ultimately about the search for God, and how unfortunately everything we find joy in on earth is ultimately subject to death, decay, demise. But now I truly see how the whole plan and purpose of God is indeed, as the scriptures say, to restore, redeem and transcend (go beyond) all we know of this: “For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in Him [Jesus], and through him to reconcile to himself ALL THINGS, whether things in heaven or things on Earth, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross” (Colossians 1:20).

So for those of us know who know Jesus, who have put their faith in Jesus, in his death on the cross for us and resurrection, and thereby become “a new creation” whereby our spirits are united with God’s Spirit, what seems like a scary and horrible event is indeed the beginning of “a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and earth had passed away, and the sea was no more” (Revelation 21:1).

Now, could you possibly get more transcendental than that?** Maranatha! (Come, Lord Jesus!)

*CS Lewis’s list of seven forms of romanticism (as in literature) include 1. Adventure stories, often including exotic locations, eg Treasure Island, Robinson Crusoe, The Lost City of Z, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea; 2. Fabulistic or fantastical stories, eg his own Chronicles of Narnia or Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, fairy tales and/or science fiction in general; 3. stories dealing with ‘Titanic’ characters, eg Beowulf, Fionn MacCumhail, Greek myths; 4. macabre and surrealistic stories, eg the writings of Edgar Allen Poe, Frankenstein, Kafka on the Shore, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, etc; 5. Stories where egoism and subjectivism feature heavily, eg The Bell Jar, The Catcher in the Rye, Metamorphosis, Notes from the Underground; 6. Novels about revolution or revolts against civilisation/tradition, eg Les Miserables, Mutiny on the Bounty, Animal Farm, The Sympathizer, etc; and 7. Writings or art romanticising nature/the love of natural things, eg the writings of Henry David Thoreau, William Wordsworth, Walt Whitman, etc.

(As Bradley J Birzer concludes in his article on this for The Imaginative Conservative, “Only, really, in the last of these categories could one firmly place what is normally defined as ‘Romantic’ in the sense of the Romantic authors of the early nineteenth century,” eg what is normally construed as the Romanticist movement. I must admit, I have always considered myself an echt [true] romantic, since virtually all these forms have appealed to me deeply at some point in my life.)

**Speaking of which, my very first experience of spiritual ‘transcendence’ occurred when I was 17. At the time, I was travelling along the famed US Route 66 highway with my then-hippie boyfriend (who perhaps ironically was named Virgil) over the summer holidays, and we decided to stop at the Grand Canyon and admire its stunning panorama. As I climbed down into the canyon and stretched myself out on a rock, I suddenly became aware of a tremendous presence that seemed to be related to something ancient and eternal. At the time, I simply attributed this to the canyon’s estimated 1.7-billion-year age.

However, as I laid on this rock and meditated, I suddenly had a profound sense of leaving my present earthly existence and becoming one with whatever this presence was. At the time, as I was reading Nietzsche for an Advanced Placement English course I was due to start in the autumn for my final year of high school, so when I finally emerged from the canyon, I ecstatically declared to Virgil, “I’ve just transcended the ego!”

This spiritual experience in nature led me initially to change my self-described philosophical views at the time to being a “pro-pantheistic Christian existentialist” (I only used the term ‘Christian’ vaguely as although I had been leaning towards atheism — or as much towards atheism as one can get as a romantic — It was only later, after I came to faith in Christ, I realised that what I had experienced in the Grand Canyon was the eternal presence of God, or what my native American forbears call The Great Spirit.

I know comments are passe these days, but this is wonderful work! I’m wondering if you’re on substack?

LikeLike

Thank you Joe for the praise – I am not yet on Substack, but may eventually transfer there. Also I don’t see any reason why comments should be passé – I appreciate every comment I receive!

LikeLike