As my recent trip to the Netherlands revealed, there is so much to discover and admire about this small yet mighty country, notwithstanding the darker elements of its colonial past. These are some key highlights and takeaways.

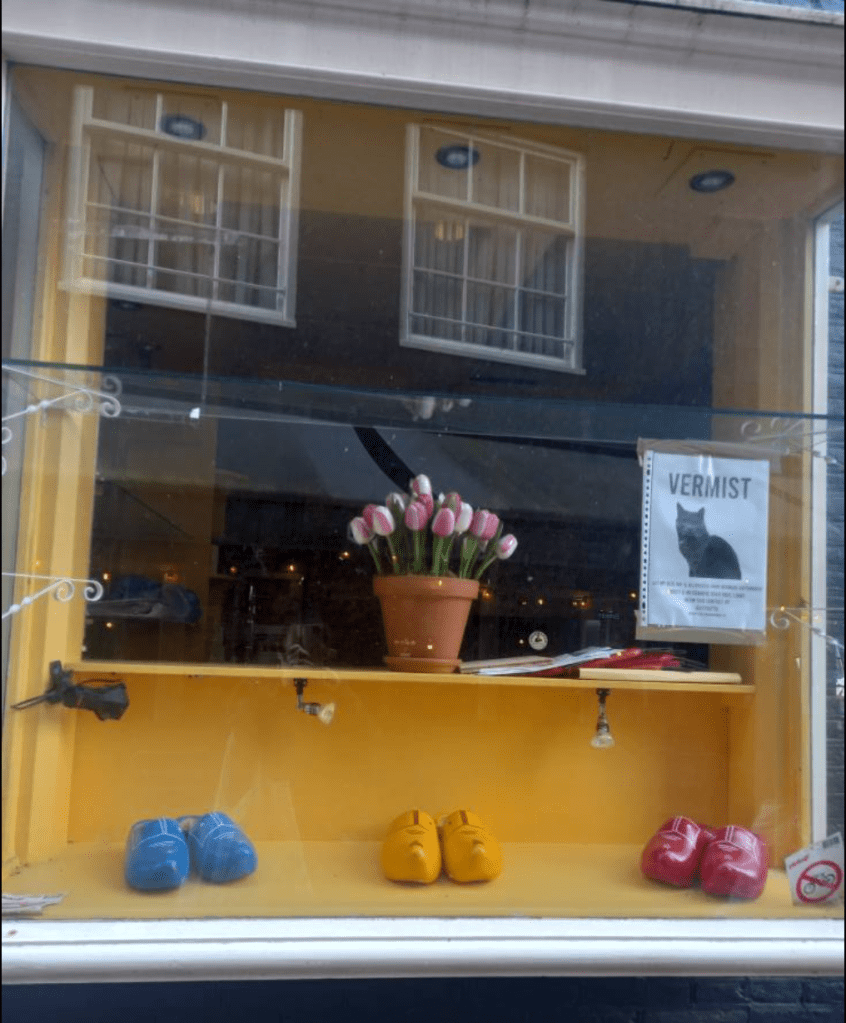

When you think of the Netherlands – or ‘Holland’ as it is often mistakenly called (Holland proper is only two provinces, North and South Holland, of the country’s 12 provinces and 342 municipalities) – what usually comes to mind are the things the country is most famous for: vibrant, multicoloured fields filled with row upon row of every variation of tulip one could imagine; windmills, used to manage the flow of water across its numerous polders (low-lying land masses the Dutch reclaimed from the sea by an ingenious engineering feat involving dykes, canals and… windmills); painted wooden clogs, traditionally worn by Dutch farmers working their seawater-reclaimed fields; rich, creamy rounds of Edam and Gouda cheeses covered in red wax; blue-and-white Delftware pottery, a home-made imitation of costly Chinese porcelains; canal-veined cities lined with charming houseboats, flower-filled bicycles and tall, narrow houses with their signature scalloped, gabled roofs (halsgevels); and world-renowned museums filled with works by some of its most influential artists – Rembrandt, Vermeer, Hals, Van Eyck, Bosch, Van Gogh, Mondrian, to name but a few.

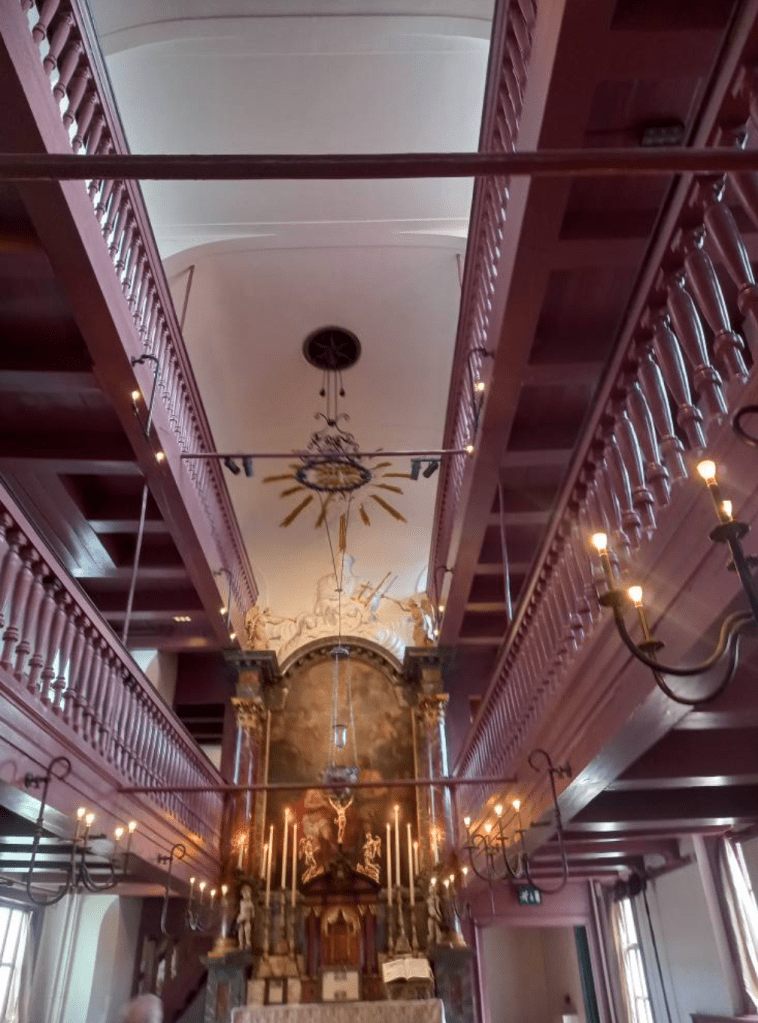

Many who come to Amsterdam – the country’s second-largest port after Rotterdam, the biggest port in Europe and the world’s 11th largest port – do so as much for its infamous ‘Sin City’ reputation as for its network of stunning, tree-lined canals, rightly earning it the title of ‘the Venice of the north’. As a city founded on and greatly enriched by international trade (more on this below), it has long welcomed people from across the world, including refugees fleeing from religious persecution who found a haven in its narrow alleyways and hidden places of worship. These include the intriguing Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder (’Our Lord in the Attic’) Museum, a hidden Catholic church in the attic of a 17th century merchant house – one of two still standing – and the beautiful Portuguese Synagogue in the old Jewish quarter, built in 1675 for the many Sephardic Jews expelled from Portugal and Spain in the 15th and 16th centuries, which also houses the world’s oldest Jewish library (Ets Chaim).

Yet Amsterdam’s background of religious tolerance also led to it becoming a centre of progressive thinking and liberalism, notorious for its ‘anything goes’ permissiveness. Since the 1970s, tourists have been flocking here in droves to enjoy hedonistic party weekends, titillated by the abundant opportunities for nightclubbing, drinking Heineken, sampling its famed coffeehouses where you can freely buy and smoke cannabis and other ‘soft’ drugs, or visiting the infamous red-light districts (Rosse Buurt), such as De Wallen. In this area, inside its Mediaeval, cobbled-street centre near the 14th century Oude Kerk (old church) and the Anne Frank House museum, you can wander around gawking at its 300 one-room red- or black-lit cabins where prostitutes openly flaunt their services amid an array of other sex shops, sex theatres, peep shows and even a sex museum. Notably, the Netherlands was the first country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage (2001) and euthanasia (2002), and the Dutch are equally renowned for their permissive attitudes towards prostitution, recreational drugs and LGBTQ+ rights.

As for me, my personal motivations for going to Amsterdam – apart from joining the fun and fantastic inaugural Amsterdam Salsa Weekend and joining its fun-filled canal cruise (if going next year, make sure to join it), being there at the start of the spring flowering season and travelling on by train to visit my friend Melanie in Den Haag – were because of my continuing curiosity about this seemingly paradoxical country and its peoples. What is it that makes the Dutch so famously artistic and industrious, as well as so infamously permissive – especially in a country that was once fervently religious, known for its strict Reformation-era Calvinist teachings? What is it about these easy-going, placid-seeming and endlessly pragmatic peoples that makes them so welcoming and tolerant towards exotic cultures and practices? And how did such a small country – much of it reclaimed from the sea – become such an influential, world-leading power?

These are questions I’ve been asking while researching my historical fiction novel-in-progress, which was another reason for my visit.

Research motivations and revelations

They say if you if you like Amsterdam, you’ll like the rest of Europe. Indeed, while undoubtedly unique, its characteristics also at times resemble a mixture of other European cities such as Berlin, Bruges, Ghent, York, Prague, and Scandinavian cities like Copenhagen and Stockholm. Its Venice-like canals and artists famous for emulating the chiaroscuro techniques used by Italian master Caravaggio also lend it a more Mediterranean feel. Its architecture is simultaneously Mediaeval, Baroque, Gothic, Early Modern Era and eminently contemporary, reflecting centuries of European history. Knowing something of the Protestant Reformation (1517–1648) and Catholic Counter-Reformation (1545–1648), it is almost as if Amsterdam’s very stones reflect this conflict, as traces of both religious movements can be found across the city.

Then there is the phenomenon of Dutch citizens’ remarkable competence in multiple languages, including English, which is not only widely spoken but is also the nearest linguistic equivalent to English. And although it is full of peculiarly Dutch characteristics, Amsterdam feels international, but in a particularly European way – like a microcosm of all that is essentially European, or even essentially human. Perhaps this is thanks to its legacy of thinkers such as Desiderius Erasmus, the famous Dutch scholar and Renaissance humanist who was a leading figure in the European Enlightenment.

But despite having lived in Amsterdam for two years in my early 20s (I worked in the communications department of Jeugd Met Een Opdracht (Youth With a Mission) in the building opposite Centraal Station with the words ‘God Roept U’ [God loves you]; I also spent many days and nights ministering to prostitutes and drug addicts in the nearby Zeedijk), I never understood why there were so many Surinamese and Indonesian people in the city, or why the Dutch national dish is rijstaffel (literally, rice table) and why a typical street-food snack is chips met sate (chips with Indonesian satay sauce).

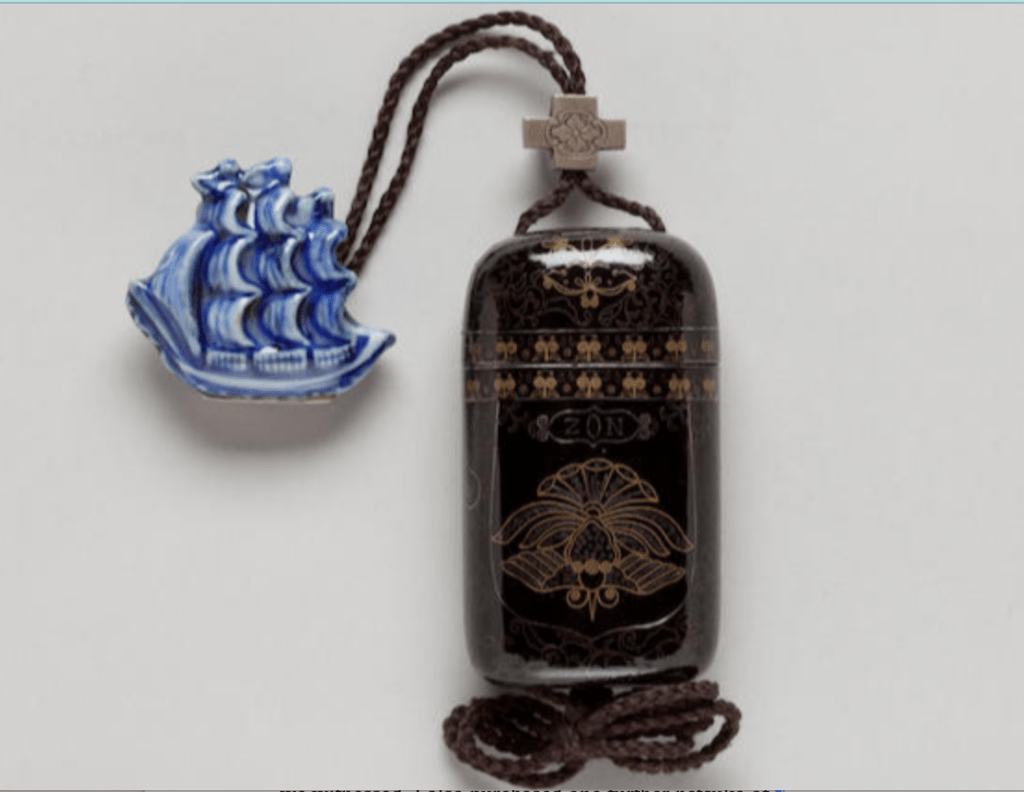

That is, not until some 25+ years later, when I visited the ‘Kyoto to Catwalk’ exhibition at the V&A and learned about how the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC) had a lasting impact on Japan, being the only Europeans allowed to live and trade in the country during its 200+-year sakoku isolation from the outside world. I had never heard of the existence of the fan-shaped artificial island called Dejima in Nagasaki, Kyushu, Japan, where the Dutch lived and traded, but I was fascinated by the exchanges in knowledge (medicine, science, arts and crafts, etc) between the two countries. How could I have lived and worked in Amsterdam for two whole years and never heard of the VOC or known of its role in Japan?

One element of this exhibition that particularly intrigued me was a cabinet filled with netsukes (small, intricately carved toggles usually attached to an inro [a small box used to carry things, eg snuff, which would hang from men’s obi sashes] – now very popular as collectors’ items, in part thanks to Edmund de Waal’s best-selling The Hare With Amber Eyes). Among these was a large netsuke of a Dutchman carrying a rooster (apparently the Dutch engaged in cockfights during their long periods of seclusion on Dejima), next to another netsuke of a beautiful Japanese dancer. This made me wonder: what would relationships between the Japanese and the Dutch have been like then? I can’t possibly imagine two such wholly different peoples! Then I recalled Vincent van Gogh’s obsession with Japanese prints; was this also due to this connection?

I decided to research and write about it as a way of answering these questions – hence the raison d’etre for the historical fiction novel I have been working on for the past four years. (I now have more than enough material for three or four novels; I’ve also written about my research trip to Japan in a post last year, including my visits to the Dutch VOC factories in Hirado and Nagasaki, as well as key Edo-era Christian sites [see here].) I began reading everything I could find about the VOC and its highly successful ‘silk for silver’ trade negotiations with Japan, which was what funded the company’s ludicrously lucrative spice trade. I also researched the various events in Japan that led to it forming a ‘special relationship’ with the Dutch after expelling the Portuguese.

Until I began this research journey, I had little or no prior knowledge of the VOC, which, as it turns out, was an incredibly significant entity. For example, the VOC was the world’s first multinational corporation and the first to implement branding via its recognisable logo; it was also the first company to issue publicly traded shares, contributing to present-day stock exchanges and financial markets. It was a key contributor to the development of global trade networks, and its colonial activities were a precursor to modern-day globalism, as well as to the spread of capitalism. Also, its mariners discovered the continent and islands of Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand.

But the real mind-blower is that its domination of the East Indian spice trade made it the richest company the world has ever seen, in its heyday earning the equivalent of $7.4–$8.28 trillion, or more than 20 of the world’s largest corporations combined. Who would have thought you could get that absurdly rich from nutmeg, mace, cloves, pepper and cinnamon? Well, the Dutch certainly spotted – and ruthlessly monopolised – that niche market! And let’s not forget its additionally highly profitable privateering operations, mostly via attacking the richly laden galleons of its official Portuguese and Spanish enemies – effectively, a legalised form of piracy.

Who would have thought you could get that absurdly rich from nutmeg, mace, cloves, pepper and cinnamon? Well, the Dutch certainly spotted – and ruthlessly monopolised – that niche market!

Yet among some of the VOC’s more positive contributions – such as promoting cultural exchange via scientific learning, medicine and the arts (referred to in Japan as rangaku or ‘Dutch learning’) – there were also many dark, shameful and negative aspects of the Dutch colonial presence. For those who, like me, never knew much about this, the Dutch trade empire was truly global, spanning Africa, Asia, both Americas, and both the East and West Indies. There was in fact also a Dutch West India Company – the GWC, or Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie – which had 92 Dutch settlements in Brazil, Guyana, Surinam, the Caribbean, North America and several countries along Africa’s Gold Coast. However, although it also traded in fashionable commodities such as sugar, coffee, cacao, tobacco, salt and cochineal, it was primarily involved in the triangular transatlantic slave trade. This has already inspired me with the subject of my next historical fiction project – a real-life artist who worked with the GWC in the West Indies.

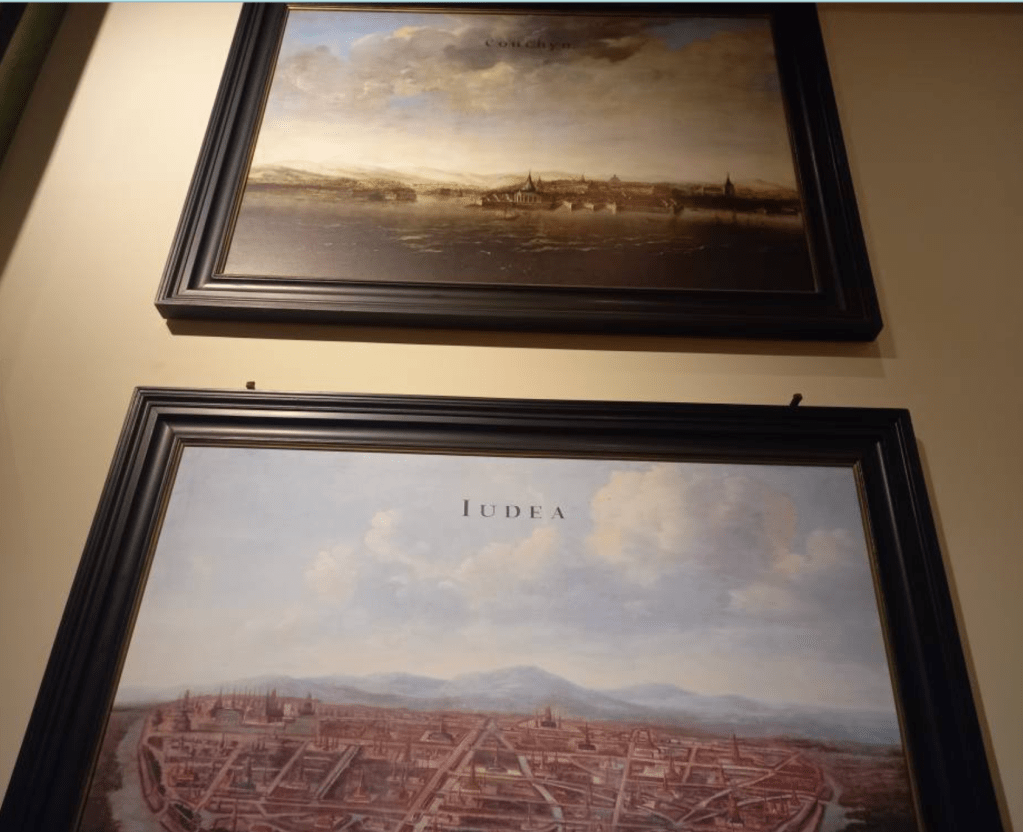

I now realise the national stain of the GWC’s involvement in the cruel transatlantic slave trade and the VOC’s genocide of indigenous Indonesians – eg the Banda, Amboyna, Batavian and Lamey Island massacres – is most likely the reason I never heard about the VOC even while living in Amsterdam for two years. It seems as if the city would prefer to hide this legacy, almost to the extent of erasing its memory – for example, the once-proud Oost-Indische Huis compound, the original VOC headquarters, has since been taken over by the University of Amsterdam; far from containing a wealth of artefacts and informative exhibitions, there were only a handful of paintings and furniture on view – a rather paltry testament to its international powerhouse past.

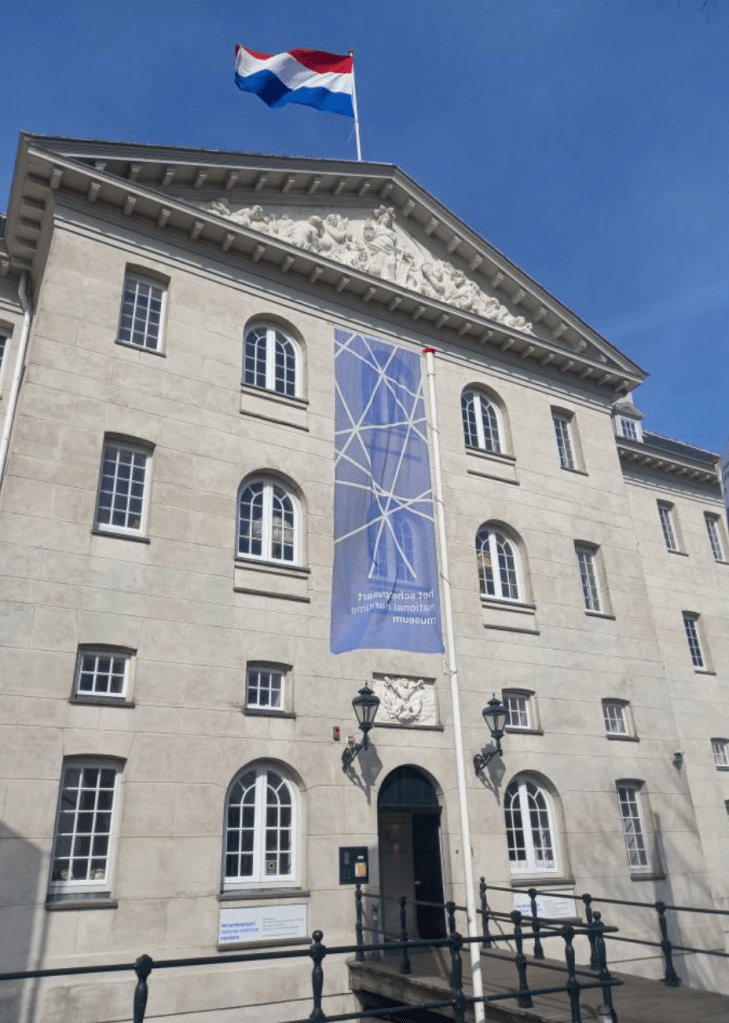

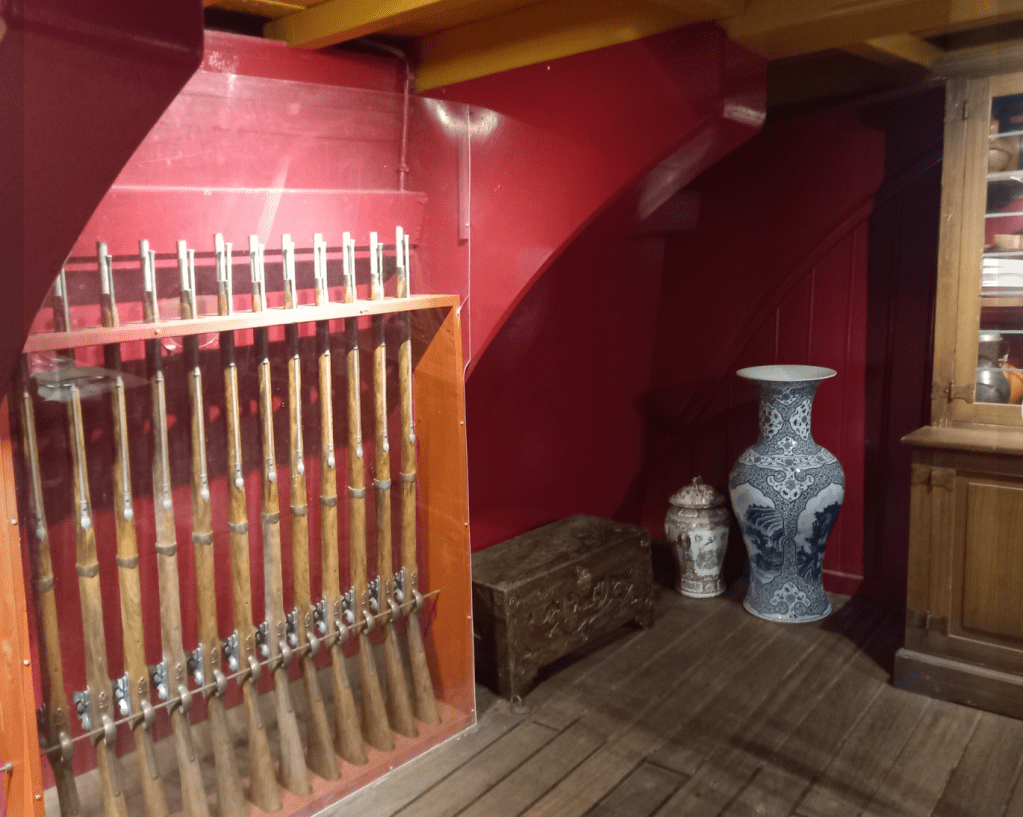

The only viable remnant of the VOC’s once-vast importance is the building’s imposing façade and courtyard, which centuries ago would have thronged with thousands of desperate recruits attempting to scale its walls, so great were their hopes of returning with riches beyond their wildest dreams. Sadly, the long sea voyage routinely killed roughly 45% of the crew on each ship (see pics below of a replica Dutch East Indiaman ship, the Amsterdam, at the city’s maritime museum, Het Scheepvaartmuseum – after years of writing about life onboard a merchantman, it was exciting to be on one!)

the Amsterdam

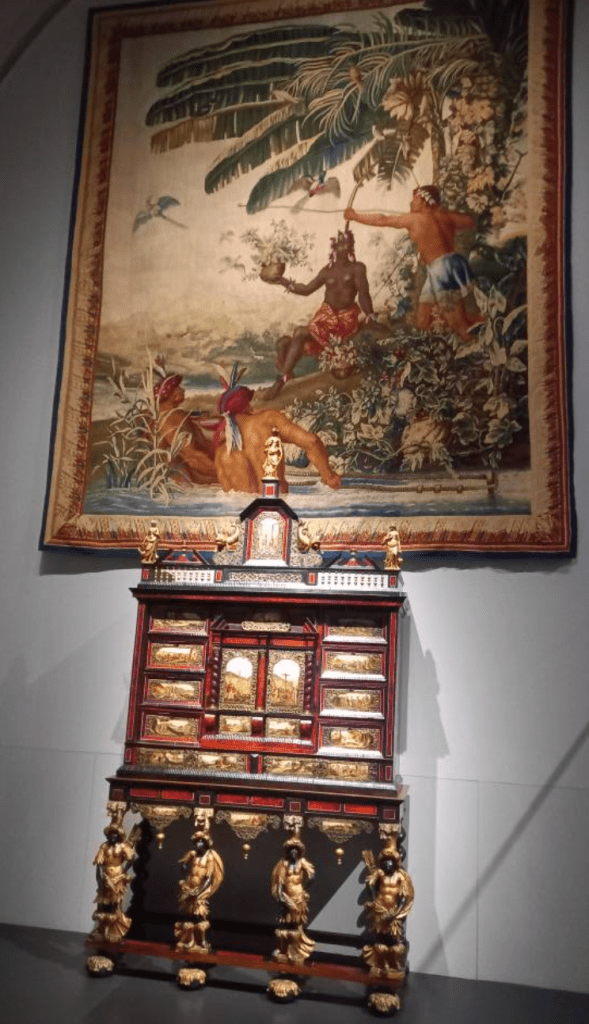

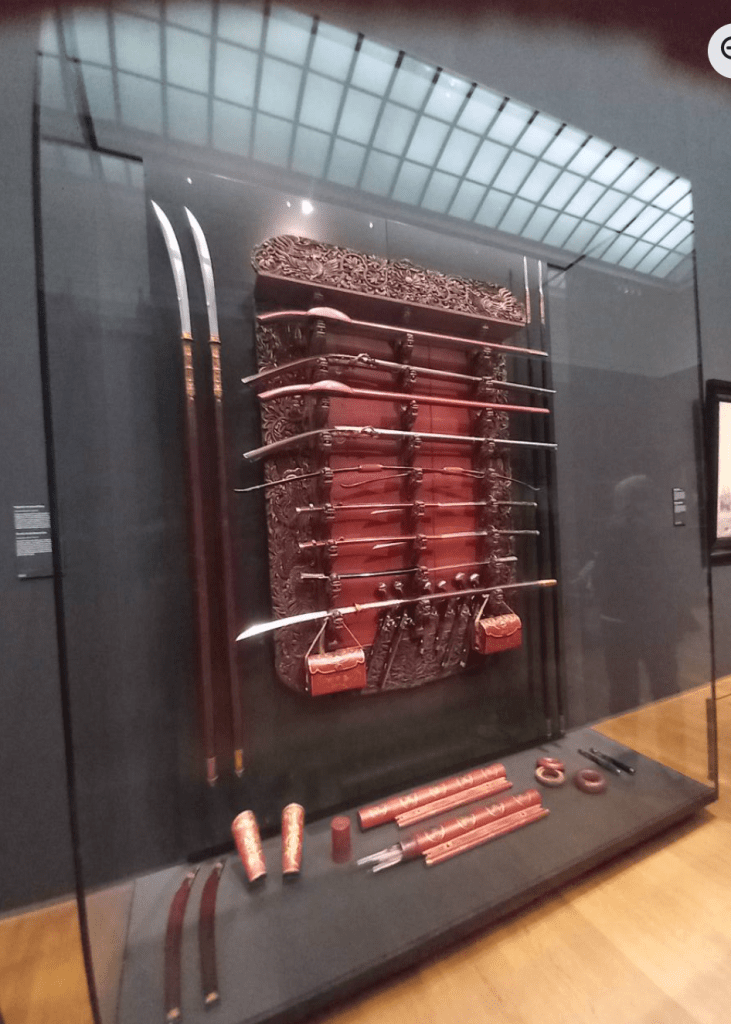

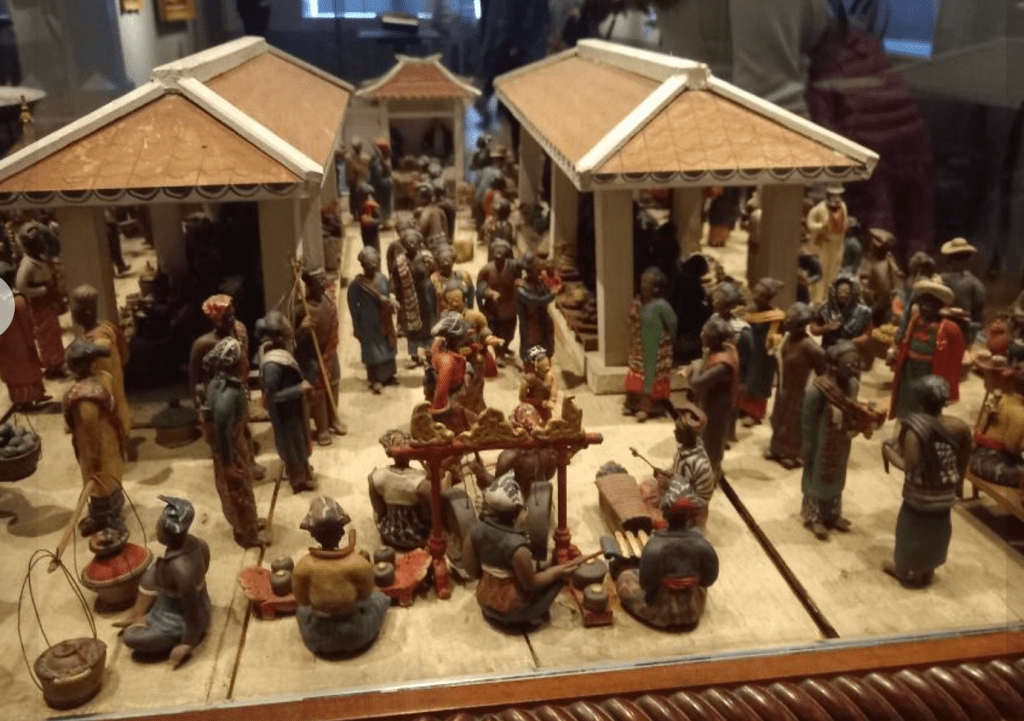

However, though it may seem hard to find direct evidence of the VOC’s legacy in Amsterdam, virtually almost everything you see and admire as you stroll its streets and alleyways can be attributed to its spectacular trade success in Asia and the New World. This not only financed and furnished the most resplendent houses visible along the prestigious Herengracht, Prinsengracht and Keizersgracht canals, but also provided patronage for Dutch Golden Age artists to produce all those illustrious works of art showcased in the Rijksmuseum (which also contains several VOC and GWC paintings and artefacts, some retrieved from shipwrecks).

Although it was clear from viewing the VOC and GWC artefacts on display in the Rijksmuseum and the legends accompanying these that the museum is earnestly attempting to address the injustices of slavery perpetrated in the name of commerce, it is also true that much of its magnificent artworks and other treasures would likely never have existed without the VOC – arguably, without the VOC’s success, the United Republic of the Netherlands might never have existed either. And its travels also uncovered other scientific marvels, such as the botanical specimens brought back from the new world (some of which you can see in the city’s small but worthwhile Hortus Botanicus).

Deep dives in the VOC archives

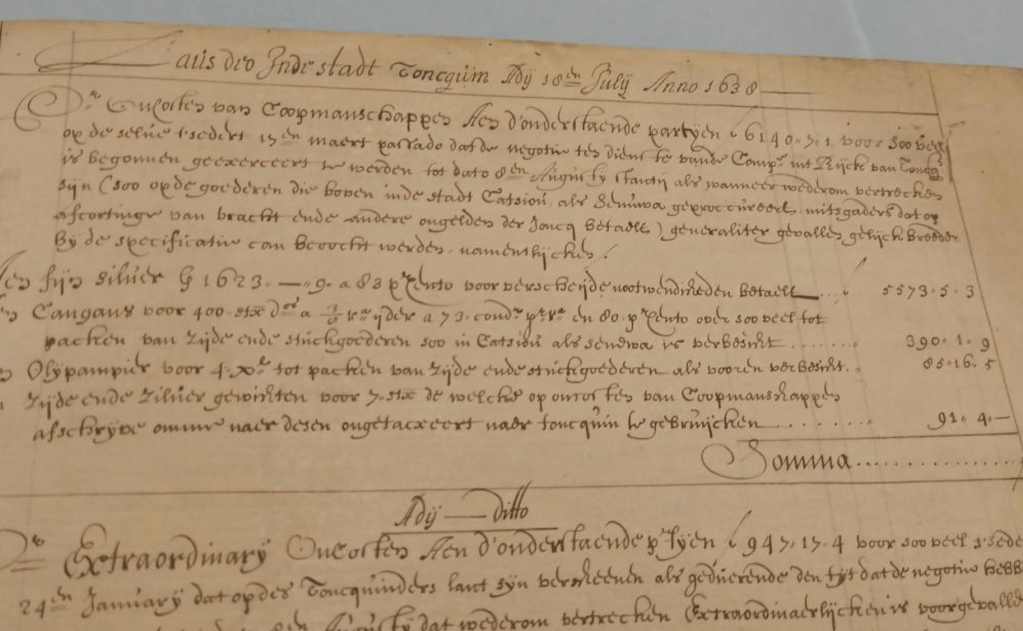

After a week of dancing and visiting the above in Amsterdam searching for vital evidence about the VOC’s background and legacy, I then went down to Den Haag by train to visit the Nationaal Archief, which is where most of the original book-keeping ledgers and documents pertaining to the VOC in Japan and other locations relevant to my novel – eg Tonkin (northern Vietnam), Formosa (Taiwan) and Batavia (Indonesia) – are to be found.

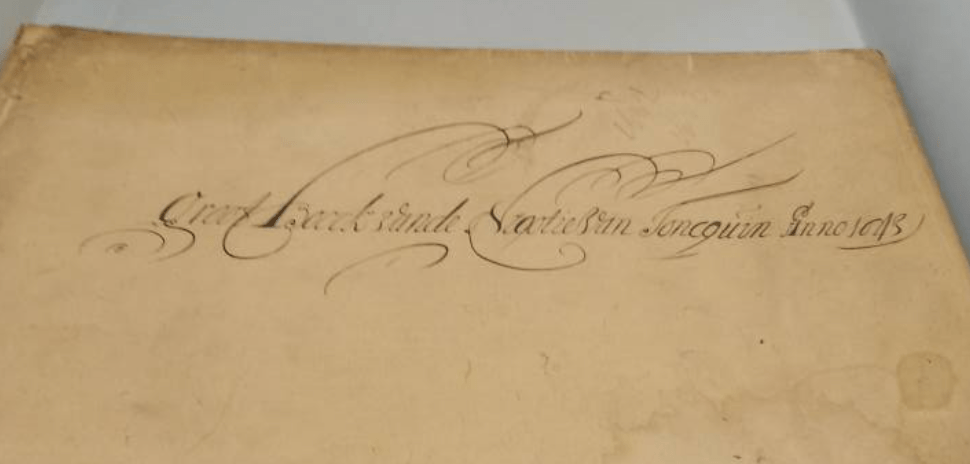

Being that since 2003, these have been listed as a UNESCO world heritage (Memory of the World), they are quite valuable. Not only do they contain detailed information concerning the day-to-day activities and expenditures/profits of the Dutch East India Company, but they also record the company’s actions and the impacts of its colonial presence on the various societies in Asia with which it interacted over the 17th and 18th centuries. While the Huygens Institute and its partners have been in a process of scanning, transcribing and digitising the documents, with five million scans thus far for their GLOBALISE project, some of these digital archives – as per the info available on the official VOC site – were either difficult to make sense of or even at times contradictory, therefore, I still felt a great desire to see and handle the original papers myself.

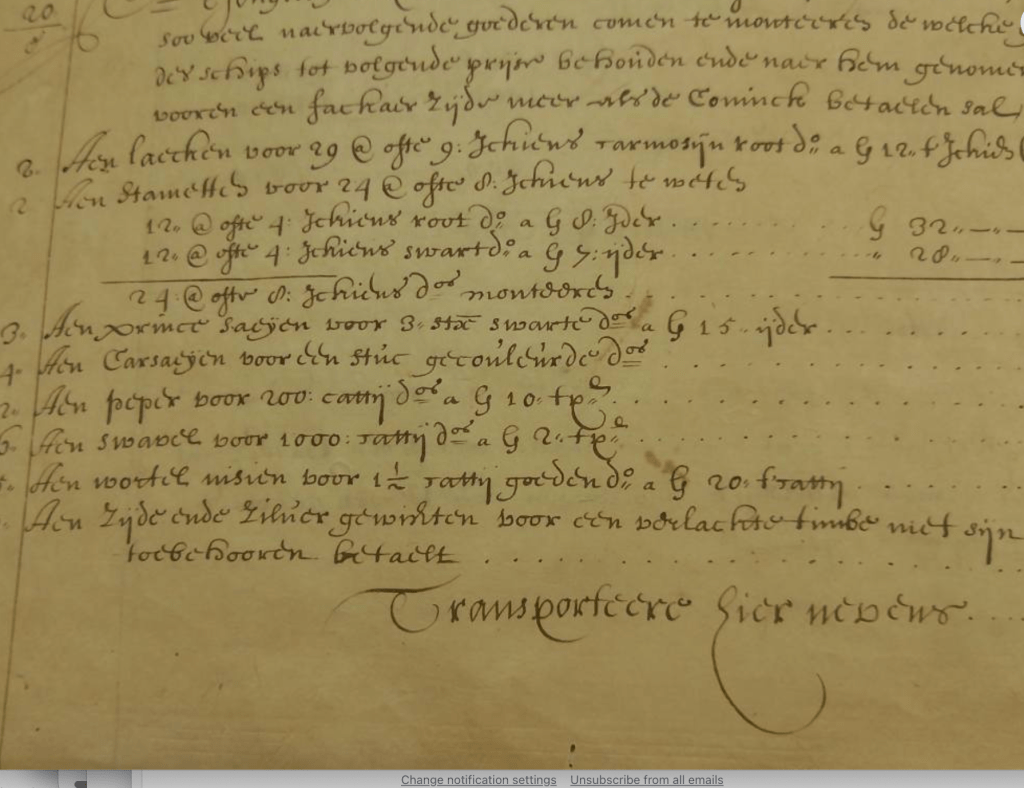

Of course, in view of both their historical value and the fragile condition of these centuries-old documents – all of which were written in a neat, old-fashioned cursive handwriting with a quill and ink, either on parchment or in bound book-form ledgers that had survived ship transfers, etc – the Nationaal Archief staff understandably have quite stringent policies on the conditions in which people are allowed to view them. Researchers are usually required to reserve documents in advance and schedule a time to pore over these in the building’s Reading Room. Although I had exchanged several emails requesting to view several documents from their online inventory, I didn’t receive a conclusive reply before I was due to travel, so in the end, I just went there in the hopes I could persuade them to allow me to be admitted to the Reading Room to view these.

Den Haag

in Tonquin (Tonkin – North Vietnam) from 1643

Thankfully, the Dutch National Archives building is in Den Haag’s Centraal Station, so it was easy to go straight there once I arrived after leaving my luggage in a locker at the station. I then had to queue for an hour or so before I could present my request. I do thank God for the sudden inspiration of explaining that as one of my novel character’s jobs for the VOC was schrijving (bookkeeping), seeing the actual paper and writing would add essential authenticity to my story. I was thrilled when they smilingly accepted my request and agreed to look up the documents to see which were viewable, but I still had to get an official ID/Nationaal Archief card made and wait another few hours before the documents could be found and made available to read in the Reading Room. By the time the staff brought out the large box filled with hand-written ledgers spanning several years of the company’s trade in silk and other goods from Tonkin to Hirado, it was nearly closing time, so in the end I had to leave and return the next day.

The results of [using Google Translate] were so hysterical I laughed out loud – for example, one of the phrases said ‘Keep on trucking’, hardly a phrase in use in 1638!

While on the first day they had told me I’d need to purchase a USP to be able to make scans of the documents onto my laptop and had also insisted on setting each ledger on a silk pillow, on the second they said I could use my smartphone to take pictures. It occurred to me I could use my camera with Google Translate to help decipher the handwritten script, which was also in an older version of Dutch. The results were so hysterical I laughed out loud – for example, one of the phrases it picked out was ‘Keep on trucking’ – clearly not an expression that would have been in vogue in 1638!

It also rendered many of the words in a range of languages – Greek, Latin, Danish, Afrikaans, German, French, Swedish, English, etc – which if nothing else confirmed the international composition of the VOC staff. However, I did get some useful contacts from the staff, who also informed me there was a gap in the records during a period in which, due to the dramatic needs of the story as well as to inconsistencies I’d uncovered online, at least made me feel better about being creative with the facts. Now that I have my pass, I hope to revisit in future!

Tilting at windmills?

Although my research efforts as above were at times frustrating or even disappointing, I did discover many things of incidental relevance to my novel. For example, when Melanie took me for a wander around the wonderful city of Delft, I discovered the building that now houses the Vermeer Centrum Delft museum was originally the Delft home of the Guild of St Luke, the official fraternity of artists and artisans that fostered the careers of many Dutch Golden Age painters. This was useful for me, as I had described my artist character’s membership of the Guild of St Luke, though he would have been in the Amsterdam chamber.

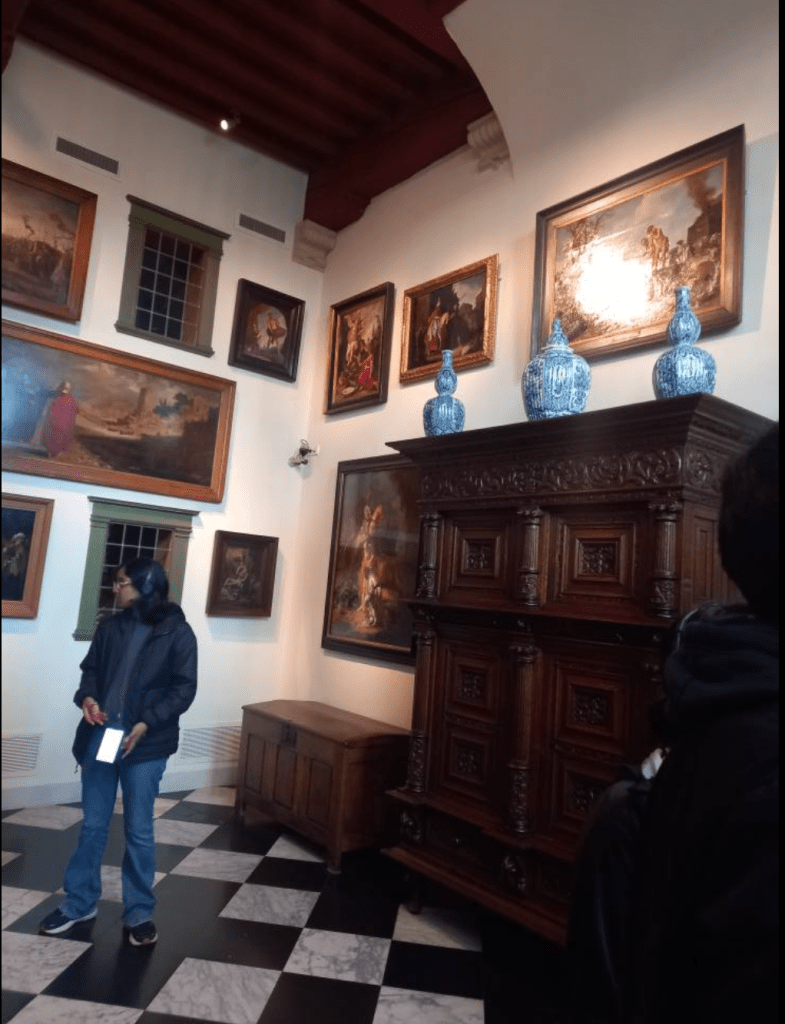

I also benefitted from visiting the Rembrandthuis museum and seeing how 17th century artists’ paints were made (stone or other natural substances were ground into a powder with a mortar and pestle, then mixed with linseed oil to make a smooth paste), the brushes, palettes and easels they used to paint with, and Rembrandt’s students’ and assistants’ copies of his works.

However, the most fascinating takeaway was the artist’s personal collection of exotica sourced from various VOC and GWC voyages – samurai and conquistador helmets, native spears, Amazonian Indian headdresses, butterflies, rocks, plants, and various animal skins, shells and skulls (see pics above). This certainly provided a unique insight into how the companies’ voyages in Asia and the New World fuelled both the artistic output and imagination of one of the Netherlands’ greatest artists.

It was also fabulous to visit some of the country’s other charming cities, landscapes, markets and vibrant cultural life; I was indeed very grateful to my friend Melanie for kindly taking me so many places – the Winkel von Sinkel Sunday salsa event in Utrecht, which had a great crowd of dancers; Delft, for a wander around its beautiful city and nice lunch by the canal; to the harbour at Scheveningen for a tapas dinner in a trendy (and pricey) new restaurant; to see some of Den Haag’s sights and sample its incredibly inexpensive (by UK standards) flower market; for lunch and cocktails at a groovy seaside beach club in Nordwijk; and for an inspiring art walk with her legal historian friend Esema and a classical music concert in the charming Roswijk neighbourhood. So yes – the Netherlands certainly has much more to offer than just windmills, tulips, sex shops and counterculture coffeehouses!

Winkel von Sinkel

So… did I solve the riddles of the Dutch character, get to the bottom of its colonial past or plumb the legacy of its contributions to the modern world? No, but after years of online-only research, it was wonderful to see some places I’d only read about or seen pics of on a screen. I will continue with my research, however, and possibly return for future visits, as this 11-day trip has made me aware there is still so much to see and learn. For now, I am still ploughing through Simon Schama’s brilliant, epic dissection on the culture behind the Dutch Golden Age, The Embarrassment of Riches – a fitting title for a culture that has been simultaneously blessed and cursed with the abundance of its spoils and its multi-hued/-storied history of exploitation and enlightenment.

2 thoughts on “From Tulips to Tolerance: Exploring the Dutch Cultural Journey”