What do you think of when you hear the quote, ‘Life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans’*? Does one of those delightful ‘God incidences’ spring to mind? Or perhaps you were just out on your normal coffee break when you lock eyes with the person you instantly know is the love of your life, or some chance acquaintance offers you the gig of your dreams. Perhaps you’ll have a surprise visit from a long-lost friend or some other encounter that changes your world forever. Or perhaps you arrive home to a house that’s been burgled, or you find yourself grappling with the devastating impacts of an unprecedented natural disaster. Or you suddenly realise that all the dreams you had for your life have morphed into a tedious nightmare, and you no longer recognise yourself. Or basically, other sh** just happens.

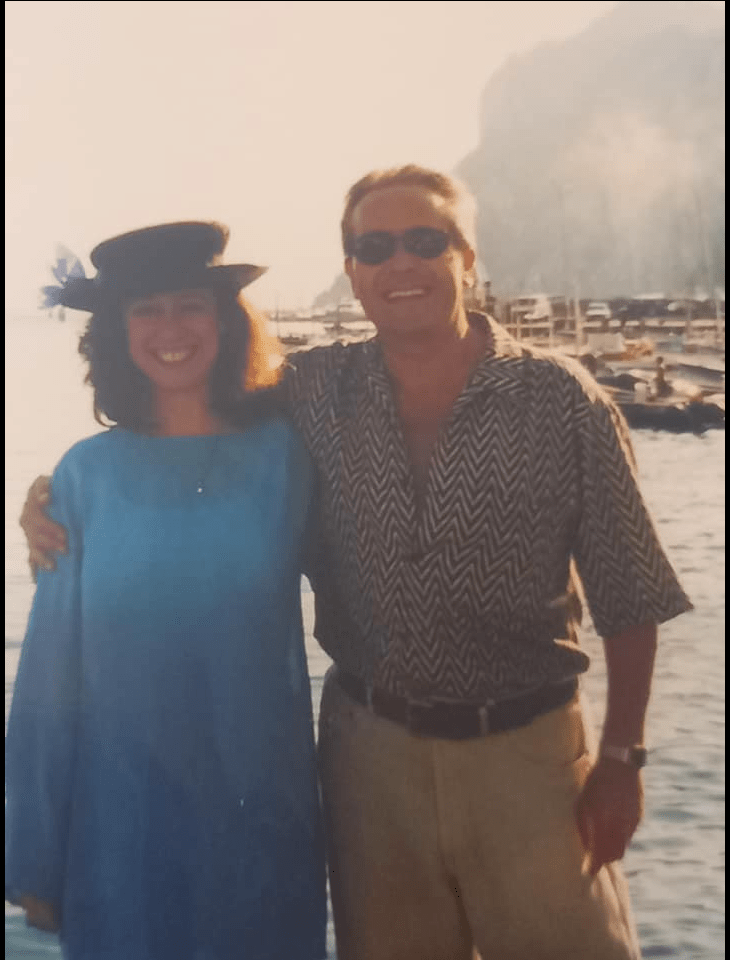

Well, welcome to my life. A few months ago, while still mourning the loss of my father (he passed away at 93, on 23 March, just before I was due to travel to Japan for novel research), I was hoping to finish and then begin revising my historical fiction novel WIP. I had also begun making plans with my beloved husband Roland to travel to Italy for our silver (25-year) wedding anniversary celebration on 20 August. Our plan was to drive via the south of France to Positano and Capri, along Italy’s famed Amalfi Coast, to relive our fantastic honeymoon, and perhaps hire a villa for family and close friends to join us. We planned to stay for the whole month of August, sipping limoncello as we watched sunsets sink behind a glorious, lemon-scented seascape.

“A little over a month, these plans were abruptly, irrevocably shattered. I went from joyous expectation of living my best creative golden years in retirement with Roland to being a stressed-out, exhausted, fretful and panicked ‘woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown’.”

But a little over a month after I had come back from Japan and we had gone to my mum in Charleston, SC for my father’s burial, these plans were abruptly, irrevocably shattered. I went from joyous expectation of living my best creative golden years in retirement with Roland to being a stressed-out, exhausted, fretful and panicked ‘woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown’.

It’s now only July, but my March/April Japan trip already feels like a dream from another lifetime. Time may fly when you’re having fun, but there’s very little about this wholly unexpected and scarily fast-moving journey I could possibly describe as ‘fun’.

How it started

This unexpected sh** happening journey began on 24 May, when Roland and I went to meet the oncologist to discuss the CT, MRI and EEG scans she’d taken of his lungs in late March, while I was in Japan. He’d begun to feel like he was struggling to breathe unless sitting up, and had a continuous, painful cough. Dr Sim said the scans revealed a very large, malign tumour in Roland’s left lung; while it had not yet affected other organs, it had spread to his lymph nodes. There were also several blood clots present. Although this indicated his cancer was already at stage 4 (terminal), we thought it sounded hopeful that the combined chemo and immunotherapy treatment she proposed could extend his life for another 2–3 years.

Roland was still vaping at this time, so was relieved the oncologist hadn’t demanded he stop; with hindsight, we should have realised this was NOT A GOOD THING. I nodded vigorously when the nurse attending this session urged him to exercise gently, though I realised just how serious his breathing issues had become when we went on a walk the next day, and I saw how he could not even manage half of the walk to the end of our street, but instead had to stop every few metres to sit on a wall and catch his breath.

Soon Roland began to experience other sudden symptoms: headaches, sleeplessness, nausea and what he described as ‘crackles’ or ‘fairy lights’ on the peripheries of his vision, and headline characters that jumbled and danced incoherently off the page. I didn’t realise how bad his vision was until he drove over a traffic island, destroying both side tyres in the process — not at all normal for a careful driver. The next morning, I woke to find him crying because of an intense pain in his arm, back and shoulder that didn’t respond to pain relief. It was clearly time to call the emergency number the oncologist gave us, which told us to go to the nearest accident and emergency unit.

We then spent a gruelling 14 hours at Stoke Mandeville A&E, waiting for a CT scan and results; the staff only informed us at 2.30am that they would keep Roland in overnight to do yet another scan in the morning. I tried to sleep in the chair next to his bed, but it was far too noisy and my eyes were playing up without the drops I put in nightly, so I decided to drive home at 3.30am — a very traumatic experience as I got lost trying to follow a confusing GPS signal down several dark, twisty country roads, and was so unnerved by a driver following too closely behind me that I ran over a poor animal in my distress.

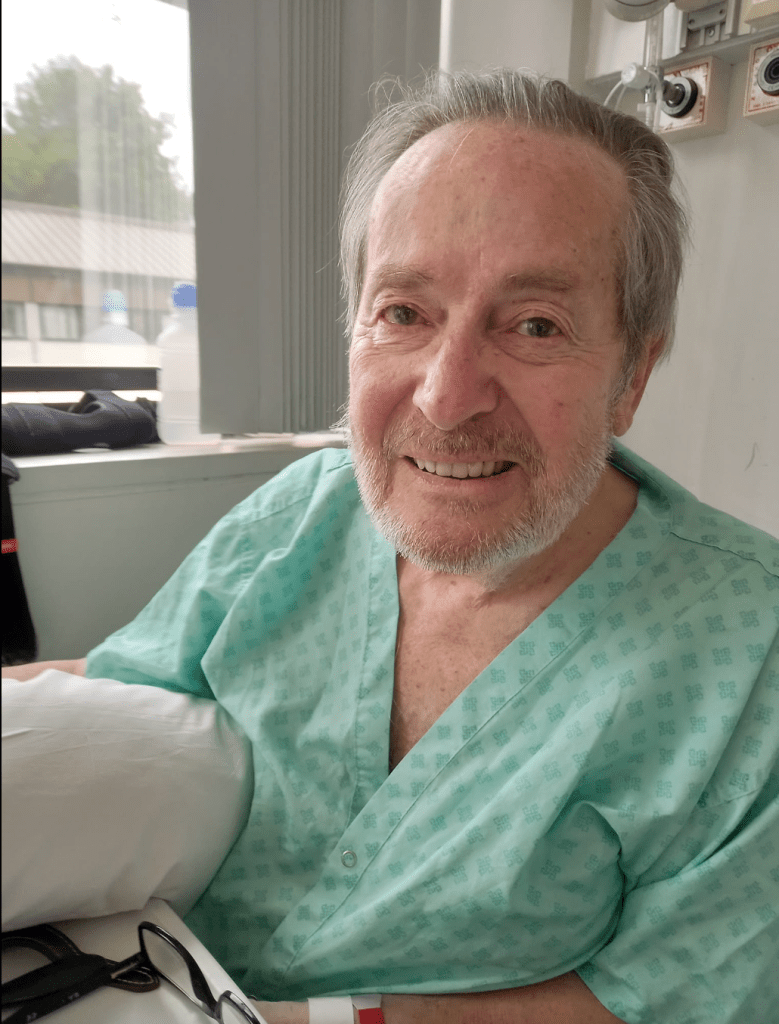

“Roland seemed his normal, jokey self, laughing at his glamorous hospital attire and woeful hospital meals. I thought it would be a simple matter of a brief chat about his scans and then he’d come home; we only thought this might help speed up the chemotherapy treatments.”

They kept him in a second night for a consultation about the MRI results, which showed he’d had a mild stroke. When I met him at hospital, Roland seemed his normal, jokey self, laughing at his glamorous hospital attire and woeful hospital meals. I thought it would be a simple matter of a brief chat about his scans and then he’d come home; we only thought this might help speed up the chemotherapy treatments.

However, the next morning I got a call from the ambulance paramedic telling me they were taking him to the stroke unit at High Wycombe Hospital because he’d had a second, major stroke overnight, this one affecting his speech and disabling his right arm. This was only 1 June — a little over a week after the initial cancer diagnosis.

The clots thicken

The following day when we were visiting him, I, my stepdaughter and stepson were each taken aside separately by a visiting consultant I thereafter nicknamed ‘Dr Doom’. Doom said the X-rays showed Roland had yet another complicating condition on top of his cancer and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder): something called ‘pleural effusion’, a buildup of phlegm or mucous around his lungs. He said in view of Roland’s advanced cancer, this additional complication was effectively untreatable, concluding that in his own estimable opinion, Roland only had ‘a few weeks at best’.

I was shocked, horrified and angry. Less than 10 days ago, the oncologist had suggested he’d have another 2–3 years with treatment; now this consultant had suddenly concertinaed this to weeks. How dare this man play God like this, oh-so-callously shortening my husband’s life by such drastic measures? Where was his bedside manner? I informed him I had only just lost my father and was not prepared to lose my husband this soon as well. ‘You can keep your damned statistics!’ I declared. ‘I believe in a God of miracles and compassion, and I and my husband will fight this together! Besides, people from all over the world are praying for him!’ Dr Doom merely shrugged and looked at me like I was nuts, thenceforth studiously avoiding me whenever we passed each other in the hospital corridors.

A week after Roland’s admission to the stroke unit, the ward’s head consultant and team of junior doctors suggested trialling taking Roland off the anti-coagulant pills (Apixaban) he had been taking for some time and instead give him ‘risky’ injections of Fragmin (Dalteparin) for one week. Despite their dire warnings, this tactic seemed to improve his condition, temporarily pausing any further stroke or stroke-like impacts and enabling Roland to begin recovering from the first major stroke. He worked hard with the physio team, slowly regaining his walking mobility, strengthening his weak arm and hand, and learned to speak slowly but normally — the slight droopiness in the corner of his mouth disappeared and he no longer sounded amusingly like a pirate. I could see how hopeful he was about coming home and resuming a ‘normal’ life, albeit realising he would need the proposed chemo and immunotherapy to extend his life.

Unfortunately, almost as soon as they stopped the Fragmin injections (they said they could only give him these for a week; one of many debatable points in his treatment) and returned him to Apixaban, Roland began having further strokes or subarachnoid haemorrhages (brain bleeds) as blood clots repeatedly attacked his brain. The second major stroke affected his memory and made him excessively emotional and weepy, something he had no control over — it was at times deeply touching or somewhat comical that he’d be in floods of tears and gratitude for the slightest kindness shown him, even when it was a nurse coming to give him an injection. The third major stroke occurred about a week later; he was sitting in the stroke unit garden with the physio team when he suddenly experienced a searing headache and lost his sight.

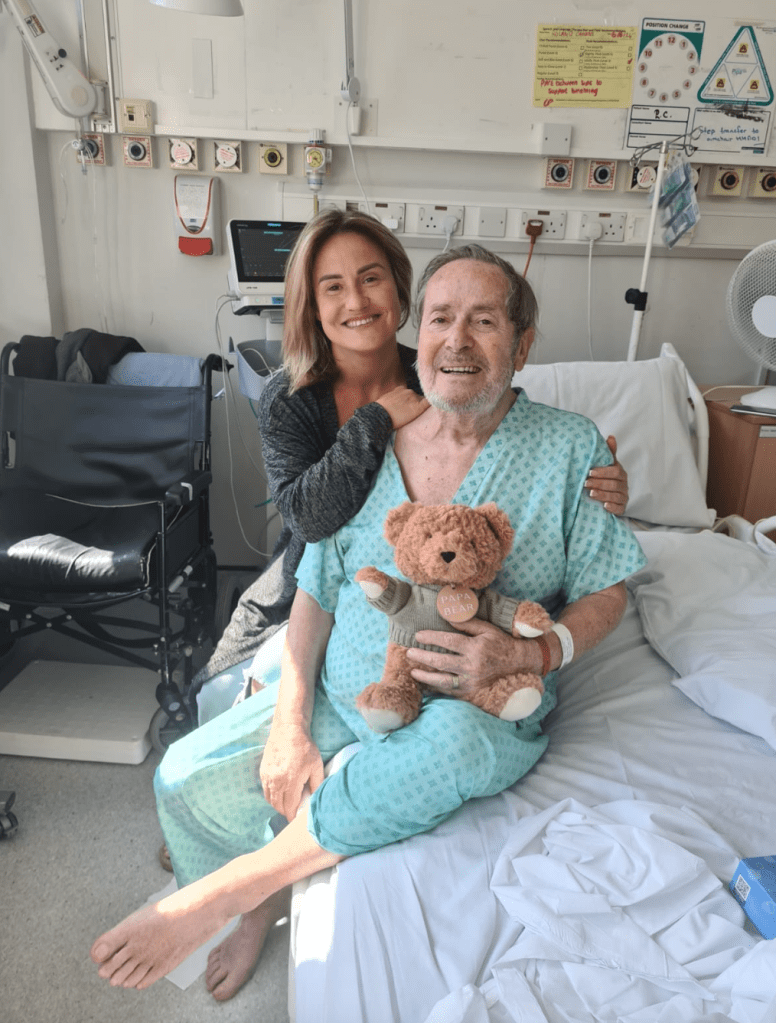

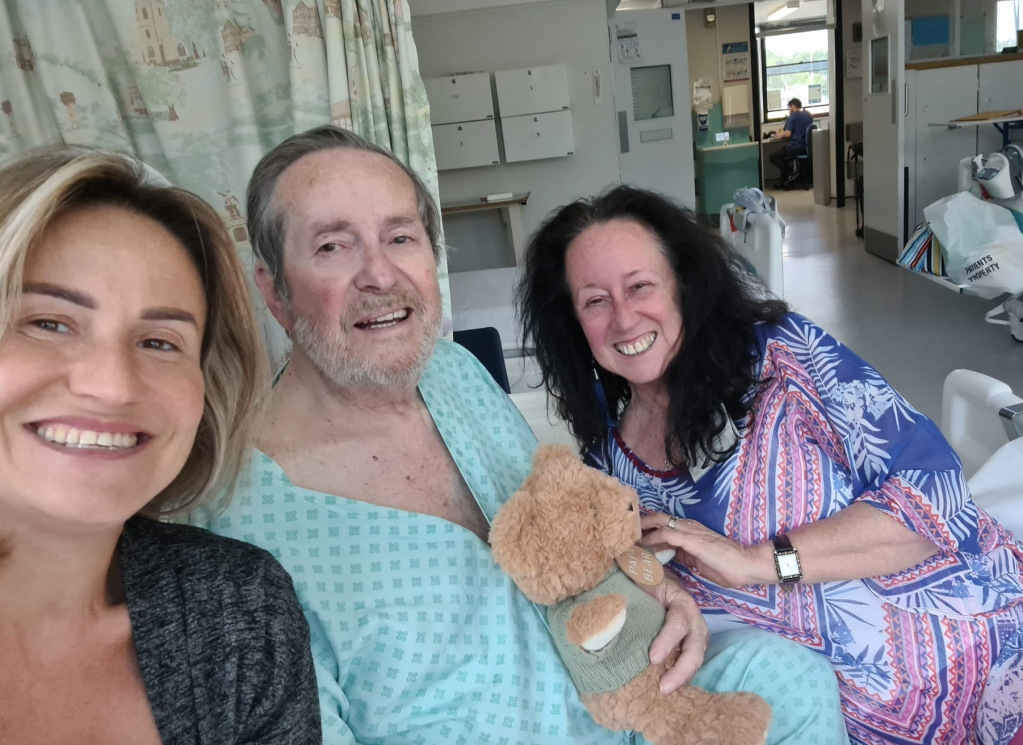

They continued to keep him in the acute bay for three weeks to monitor his breathing (oxygen levels), blood pressure (at times dangerously low), sugar levels (Roland also had type 2 diabetes) and swallowing, which was especially challenging as his problems with COPD/breathing (particularly with that problem of extra mucous buildup in his lungs and throat) made that very difficult. Roland could only comfortably manage thickened orange squash drinks, protein shakes, yoghurts and custard puddings — or perhaps might have tried to eat the pureed meals they served him for a while, but eventually got tired of eating these — so I and my stepdaughter visited him daily to bring him the kinds of soups, ice creams/ice lollies, yoghurts and drinks he would actually eat, team-tagging with each other during the day when her kids were at school to ensure one of us was always with him.

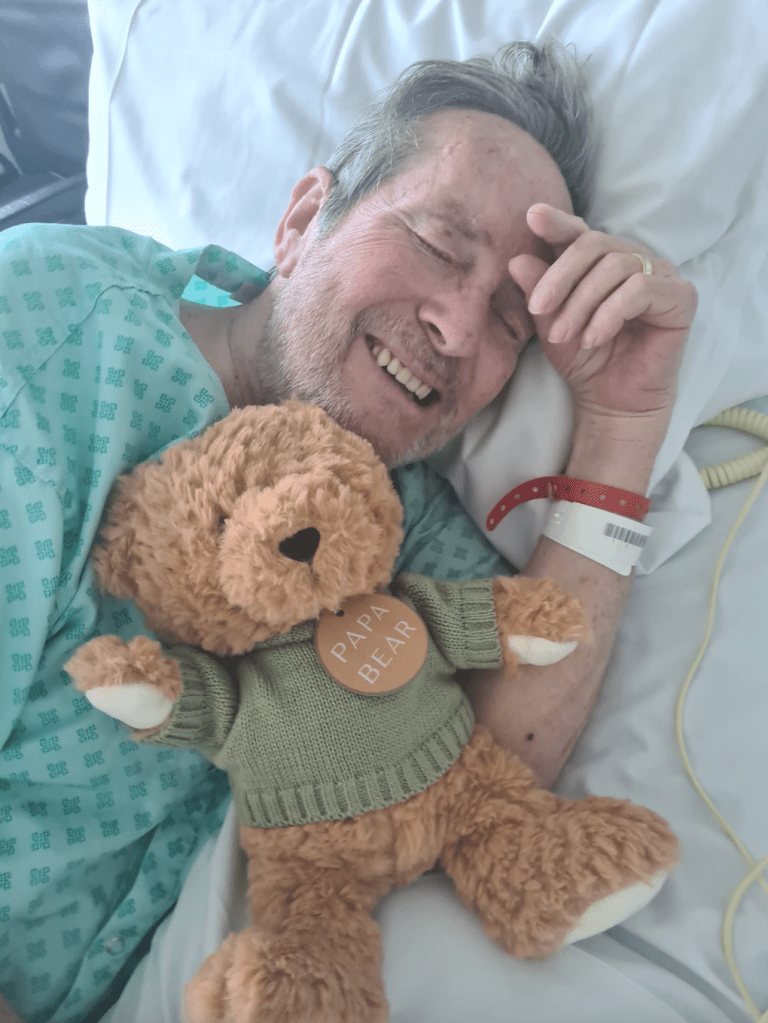

I returned every night, staying with him long after official visiting hours finished at 10pm; although it was tiring to be there so many hours each day, in retrospect, I am deeply grateful for this time, as we were able to grow closer. At one point, during his more critical observation phase, God gave me a very clear picture of him curled up in a foetal position in the ground, receiving nutrients from the sun, plants and insects in the soil. I read to him from The Overstory, which he said helped him feel connected to me.

I sat with him and prayed for him or sang gently to him whenever he became confused and disoriented, not recalling where he was or what had happened to him. I explained he’d had a series of strokes, that the thickened blood from the cancer was like a hurricane in his head, and comforted him with the image of Jesus calming the storm for his terrified disciples. I said Jesus is always with him, even if I had to leave to go home. I saw how the night nurses thought I was spoiling him, that as soon as he came home, he’d be ringing the bell every two seconds, but to me there was no choice: I had to be there, as I knew each moment with him then was precious. I’m grateful we had one night cuddling in the hospital bed when the staff were preoccupied; I just wish he hadn’t felt it necessary to mention this to the nursing staff the next day, as it wasn’t allowed.

“I sat with him and prayed for him or sang gently to him whenever he became confused and disoriented, not recalling where he was or what had happened to him. I explained he’d had a series of strokes, that the thickened blood from the cancer was like a hurricane in his head, and comforted him with the image of Jesus calming the storm for his terrified disciples.”

Once he became blind, they stopped giving him physiotherapy; we still took him into the garden by wheelchair so he could get some fresh air. However, this did not stop him being mobile. On the morning I went to collect my mum from Heathrow (she had simply announced she was coming and booked her flights from the US; much as I worried how she would cope with the long hours I was spending tending him at hospital, her presence in the coming weeks turned out to be a true godsend), I received a worried call from the ward informing me they’d found him on the floor at midnight, and had no idea how he’d got there. At this stage, he was becoming increasingly agitated and unsettled, always resisting every effort to get him to lie down in the bed as it was too hard and painful to breathe with him lying down, so I assume he simply tried to get out of the bed and then perhaps stumbled and fell onto the floor. They performed another scan that showed he’d had yet another subarachnoid haemorrhage, but it wasn’t clear whether this was the cause or effect of his supposed ‘fall’.

After that worrying episode — possibly because they didn’t wish to risk any further potentially reputation-damning issues — they gave up trying to put him into the bed, and instead set him in a big purple recliner chair, where he remained day and night. By this stage, the medical team in the stroke unit had concluded they had done everything they could for him, and he should be discharged to come home immediately; our house had already been turned upside-down to accommodate his hospital bed, commode and perch chair, and a whole cabinet for the carers and community district nurses to use. I was increasingly worried about any further oversights of his care in hospital, and anxious to get him home so we could look after him properly and ensure he still had opportunities for exercise rather than being left a bed- or chair-bound invalid.

While they deliberated about the details of his care package, one of the palliative nurses held up his release, insisting he needed to be reviewed by her ‘breathing specialist’ colleague. Against Roland’s privately stated wishes, she had the nursing team fit him with a port so that he could begin to receive subcutaneous injections of morphine. I was furious when this nurse tried to suggest, aided by this ‘specialist’ (another doctor with zero bedside manner), that he be transferred immediately to hospice — it felt scarily like their intention was to get him drugged up to his eyeballs and effectively euthanise him.

At this point, my faith in the medical profession’s compassion, coordination (since it seemed most of them either disagreed or failed to communicate with each other effectively), capacity or willingness to listen to me as the person actively fighting on for Roland’s best interests and extended life, and even their actual professional skills, was already highly strained — a recurring feature of the next few weeks.

The home stretch

Finally, as Roland himself had said he preferred to come home rather than being transferred immediately to hospice, they grudgingly assented, warning me I’d likely only have carers coming twice a day for 20 minutes each time — though in fact the care coordinator I’d spoken to had already offered a 4x daily arrangement of two carers for periods of up to 45 minutes each. One member of the community physio team came by to assess the house while we waited, and helpfully demonstrated how to assist his position in the hospital bed, but still we had to wait for what seemed like an incomprehensible amount of time before they seemed ready to let him go.

The hospital coordinated with the ambulance team, who gently carried him through our front door and seated him directly in his favourite, well-worn spot on the settee, which we’d covered with cushions to support his lame arm and make as comfortable as possible. As it was already the weekend when he came home, we had an initial succession of hijab-clad female carers — most of whom hailed from Somalia and lived in the outskirts of West London — looking after him until more locally based carers could be found. I’m grateful one of these visiting women demonstrated for us how to place our hands firmly on his chest whenever he had one of his excessively painful coughing fits, which to some extent relieved the pressure. A few of them also mentioned how, in their own cultures, it was always the women who looked after their elders, never the sons, who nonetheless received the entire inheritance. This was a sobering point, which helped me on occasions where I struggled with feeling his busy or faraway sons had mostly left the daily care for their father in the hands of us three women (me, my mum, my stepdaughter). What would have happened to him if we hadn’t been there?

Once these temporary carers were replaced by two gentle, sari-clad local Asian women, they helped maintain Roland’s mobility by assisting him to the camp chair in our garden daily as part of their routine. Although it was sad he was no longer able to sit and watch the birds as he’d always enjoyed, at least he could have fresh air and maintain some level of mobility. I was also deeply grateful for regular visits from each of his dedicated male friends, who could more easily lift him to/from the settee to the garden and/or the commode than myself and my 89-year-old mother, and who graciously loaded our fridge and freezer with food, drinks, soups and the ice creams and lollies he loved to suck on, which often helped relieve his distressing coughing fits.

We also had a succession of various community district nurses and Rennie Groves nurses coming daily to give him his Fragmin or morphine/Midazolam injections — thankfully, he did not seem to suffer any further strokes while at home, despite the increasing pain he suffered and the daily ramping up of levels of morphine (both orally and via a slow-release patch, as well as finally via syringe driver) to relieve his pain. Over a three-week period, these went rapidly from an initial 0.25ml via teaspoon or syringe into his mouth to some 35ml–40ml delivered subcutaneously via the syringe driver in a beeping box attached by tube to the port they’d put on him while he was in hospital.

“So many times I felt like I had no say or control over what they were doing; in addition to feeling powerless to stop the spread of his cancer and intensifying of his pain, it often felt like the house was no longer our own, that the circus had taken over and it was essentially the hospital all over again, just with familiar soft furnishings.”

While I fought this at times, fearing he was being drugged into oblivion and immobility far too soon, I could not argue with the fact his pain was intensifying daily, and he did in fact need as much relief as they — and we — could give him. But so many times I felt like I had no say or control over what they were doing; in addition to feeling powerless to stop the spread of his cancer and intensifying of his pain, it often felt like the house was no longer our own, that the circus had taken over and it was essentially the hospital all over again, just with familiar soft furnishings.

But despite the fact it was mostly just me and my mum caring for him after the circus of carers and nurses ceased visiting at 8–9pm, we amazed ourselves by managing to assist him physically on several occasions to move to the commode from the settee, or from the bed to the commode and then to the settee. On two occasions, we heard him crying in distress in the middle of the night, and discovered that despite his blindness, he’d managed to escape, Houdini-like, from the bed by exiting near the railing gap and using his good arm to follow the railing to the bed because he was desperate to use the commode, even with diaper-like pants fitted.

My mum gamely slept downstairs with him so she could keep watch and alert me if we needed middle-of-the-night emergency assistance or pain relief, as I found it impossible to sleep with all the noise and light from his machines (the air mattress on the hospital bed, designed to prevent bed sores, also made a constant, strange whirring noise — while it was somewhat soothing, its occasional restarts were sometimes quite noisy). While we did have occasional Marie Curie volunteer night respite, alas this still did not guarantee we didn’t have to get up in the middle of the night to assist in moving him when he was in pain or distress.

In between — or sometimes simultaneously — the daily circus visits, we also had regular or occasional visits from family and friends, including some of my friends from church and our local female vicar. They sat and talked with him, brought us cakes, made us teas and did the washing-up. Everyone who visited Roland took turns rubbing or massaging his back, which gave him some relief from the rapidly spreading cancer. My stepdaughter and I took turns lovingly massaging his feet and arms or cleaning and reinserting his dentures (a steep learning curve I referred to as a ‘dental breakdown’), and she often played calming angel or other gentle music for him, which helped soothe him to sleep, once he’d gradually assented to spending more hours in bed.

While earlier in his home stay, he was still embarrassingly ‘leaking’ tears of gratitude during these visits, always thanking people for their kindness in coming to see him, towards the end these joyful-seeming tears were replaced with tears of agonising pain. He hurt everywhere, and often screamed bloody murder whenever the carers or I tried to move him, even when we were trying to help him to be comfortable or to enable to swallow food or medicine. But after a string of hiccups with his medications or prescriptions and confusion between the various medical personnel attending him added extra layers of unnecessary stress, I finally took his friend’s suggestion and phoned 999 to help him remain hydrated, thinking they might take him back to hospital and put him on a drip. I was amazed to see how the ambulance paramedics were able to get him drinking pure, non-thickened water without causing a harmful coughing fit, simply by administering this via syringe deep into his throat. Why hadn’t the other doctors and nurses explained this simple, seemingly life-saving trick?

Hospice horrors

Finally — not long after my mum had suffered a minor fall and I’d seen the terror on her face when his deeply drugged and heavy body swayed towards her, nearly knocking her over — someone from the Florence Nightingale hospice phoned to say they had a bed in a private room available for him and would be sending an ambulance to collect him later that afternoon. I wanted to protest, to keep him with us until after the weekend, but I was also afraid the coveted private room wouldn’t be available if I didn’t say yes then.

I notified the carers of this change, but then had to ask them to come back as the ambulance delayed for several hours as Roland had suddenly made a very strong-smelling final statement on the situation, and it would be far too awful on the hottest day of the year thus far for him to have to endure a long ambulance trip without being first cleaned up. I’m unceasingly grateful for their willingness to help him at short notice; they certainly deserve far better wages for a distinctly difficult job.

We followed in the car, arriving before the ambulance, which I can only assume had been held up by numerous road closures along the narrow country lanes leading to Stoke Mandeville. Roland was visibly distressed and uncomfortable as he arrived; clearly the journey had been very traumatic for him, strapped vertically as he was in a stiff stretcher for 45 minutes until they transferred him into his hospice bed. I tried to comfort him by rearranging his position and angle in the bed as I’d been doing ever since he was in hospital, giving him one of the hospice lollies to suck on to calm him down.

We were all exhausted at this point, and my mum was hungry, so we’d planned to go eat at a pub as soon as he was settled and sleeping. First, there were forms to fill in and a few lengthy consultations with the hospice medical staff about his various drug regimens and what he could or could not eat. I was at pains to explain that he was still swallowing ample amounts of yoghurt, smoothies, soups and liquids via syringe, and asked them to be sure they kept him sufficiently hydrated and offered him an ice lolly any time he became distressed as I had done. I mentioned the half-finished lolly I’d put in the freezer, telling them to be sure to give him the rest of it.

Despite their nods of assent, I remain uncertain as to whether any of the following night and weekend staff took any notice of my carefully exhorted instructions for his proper care, as the next morning I received a call from another attending doctor informing me Roland had already ceased swallowing, which indicated he wouldn’t last the week — ‘only a few short days’. I was so distraught and exhausted I didn’t feel I could drive there safely, so gratefully accepted a lift from our local vicar friend Wendy, who offered to take us up so she could give him the last rites of holy communion (one of my Christian friends, after we’d interceded intensely for his healing for some time and I’d sensed a breakthrough, had boldly asked Roland if he accepted Jesus as his Lord and Saviour, and he had; despite his ‘lite Jew’ reticence, his sufferings had opened that door for him).

I’ll forever regret I didn’t just stay when our vicar had to leave, as Roland suddenly grabbed my arm, as if begging me to stay. How could I have been so stupid and missed that, thinking we still had time? I told him I’d be back soon, as I intended to go home, cook my mum a meal, have a brief nap and return to stay the night. My stepdaughter took my place by his side, saying she had things she needed to tell him. I knew his close friend and oldest son would be visiting him in the morning, and probably also wanted some private time with him. However, although I zonked out after dinner, I suddenly woke at 4am, vividly realising that the staff had only left him — a blind man — a plate of clingfilm-wrapped sandwiches and a pot of custard of all things, which they obviously hadn’t bothered to open or feed him.

“I’ll forever regret I didn’t just stay when our vicar had to leave, as Roland suddenly grabbed my arm, as if begging me to stay. How could I have been so stupid and missed that, thinking we still had time?”

I tried phoning the ward to complain and intended to drive back up in the wee hours, but the person who answered the phone merely said there had been no changes and advised me to save my strength as it could take several days. So the next stupid thing I did was not following my impulse to drive up then to ensure I could give him some proper nourishment and hydration, as although Roland had indeed begun to go through some noticeable changes — not least because the hospice staff had offered to shave him, not knowing he’d only want a beard trim, so had stopped halfway when he got distressed, leaving him half-shaven — all I could think of was surely their failure to feed or give him liquids via syringe had hurried his demise.

My final error — or perhaps their final error — happened the next morning. Because I knew he’d have visitors early on, I’d planned to go to church, eat quickly with my mum, then drive up and stay the night, having already arranged for a friend to drop my mum home. I was determined to bring with me all the foodstuffs I knew he could still ingest via syringe, along with the cologne I always associated with him, and laid these out, ready to collect. But as soon as I’d parked, the hospice phoned and said, ‘He’s started to go through changes; we thought you should know, considering the distance.’ Alas, because they didn’t use the actual words, ‘HE’S DYING — YOU NEED TO COME NOW!!!’ I assumed from the other things they’d said about this process of changes that it might take a few hours, so stupidly went ahead into the service. Although the sermon (on Isaiah 53, about how Jesus’ physical features on the cross were ‘marred beyond recognition’) was macabrely relevant, I kept checking my phone, distractedly.

Not long into the service, my stepdaughter texted to say Roland had passed away peacefully 10 minutes ago, not long after his friend left and she arrived. I bolted out of the church, panting as I called her to read all the final words I’d written out that morning to say to him, desperately hoping he’d somehow still hear them. I drove home, grabbed the things (minus the food) I’d meant to bring him, and subjected my mum to my broken-record wailing and self-rebukes for failing to act on my impulses, cursing the staff and endlessly asking myself, ‘What is wrong with me? How could I have been so stupid!?’ I was so distraught I completely missed the turnoff for the hospice, but as soon as we arrived, I rushed to his room and flung myself on his corpse, kissing his gaping mouth, hoping against hope I could somehow revive him, that he’d sit up and respond.

But I was too late. Roland was already gone, even though his good hand still seemed warm and responsive as I held it, begging his forgiveness and pouring out my tearful farewells. Although my stepson and his wife, who arrived not long after me, said they’d also had those ‘if only I’d come earlier’ thoughts, and comforted me with hugs and the assurance Roland would have wanted me to be in church, receiving comfort and spiritual help, I still struggled with my horror of having missed his final moments. I was also still very angry about the hospice failing to feed him — his half-eaten ice lolly was still in the freezer — and all the other medical people I’d dealt with throughout his illness who’d failed to listen to me as the person closest to Roland. At least the foreign-accented hospice nurse who spoke to me about the body patiently listened while I exhausted my litany of grudges and acknowledged their collective failure to hear me.

‘My heart will go on’

Grief is a funny thing: you think you’ve cried so much you must have completely emptied every single inner bucket, but then the slightest thing sets you off, and there you are, bawling your eyes out again.

All I really wanted to do in the immediate aftermath of Roland’s passing was crawl around the house in my pyjamas sobbing, then watch Titanic and sob some more until that creaking carcass of grief, hurt and anger was finally broken and absolved, left to sink to the bottom of the sea. Celine Dion’s famously weepy theme song about the tragic death of the heroine’s lover aboard the doomed ship — ironically the theme song of our 1999 wedding — had been playing loops in my head for days, and I felt compelled to watch it. But then again, after two full months of 24/7 stress, I was still utterly exhausted, and my immune system finally caved in, giving me a full-on head cold. I wasn’t even up for sitting numbly in front of a screen.

Unfortunately, in the immediate aftermath of a death, there’s always plenty to do: all the anxious friends and relatives you need to notify, all the medical items cluttering up your space and needing to be collected and disposed of, all the tidying away of clothes and personal care items no longer needed, all the official papers and forms and plans that need signing, doing, making, arranging. Even when your loved one is finally at rest, you can’t. It seemed I was still in the same place I’d felt I’d been in all throughout Roland’s illness and time at home where I was desperate for some privacy, some time to grieve in peace, yet even now when the house was emptied of the daily circus, it still eluded me.

“The Irish-sounding, down-to-earth district nurse who called to collect his medicines said it was common for people who were caring intensively for someone to miss their loved one’s final moments; she said, ‘the reason why is because they’re saving a seat for you, love’.”

Once my mum and I finally had the energy to sit and watch the three-hour epic film, I’ve found reflecting on it has helped ease my initial raw pains. The Irish-sounding, down-to-earth district nurse who called to collect his medicines said it was common for people who were caring intensively for someone to miss their loved one’s final moments; she said, ‘the reason why is because they’re saving a seat for you, love’. That’s exactly what I thought when we watched the elderly Rose dreaming she was once again on the Titanic, meeting her elegantly dressed lover at the clock and finally free to rejoin him forever.

When I think of Roland now, I try to see him as he was on our wedding day, so handsome, virile and strong — not how he was in his final moments, all stiff and blue, with his crazy half-shaven beard. I’m pretty sure now that’s why I needed not to be there; that wasn’t what he wanted me to see, his face ‘marred beyond recognition’.

And so, I must now embrace the message of this song. I must pack my suitcase full of our best memories, and mentally travel to those sunny Italian climes without him yet with him, knowing that as I hold these close, my heart will indeed go on.

*NOTE: This quote, while attributed to John Lennon, was actually first published in a 1957 Reader’s Digest article by Allen Saunders; other writers have probably derived a similar meaning (see this fellow blogger’s post for a similar take).

2 thoughts on “‘IT STARTS LIKE THIS’: An Unexpected Journey”