—Types of Burnout and Strategies for Recovery

Winter has never been my favourite time of year – it’s cold, it’s dark, and apart from the few evergreen trees and splashes of red berries threaded through the hedges, or perhaps a few flashes of pale-pastel clouds or vivid sunsets, it seems so colourless and void of life. All I want to do is stay in bed and hibernate until spring returns! And even though I know this too shall pass, it’s hard to wake up every morning to another unrelentingly bleak, grey day.

Yet much as I dislike winter, I know there is a reason for this season, too – just as the Earth needs a period of dormancy before she can resume her profligate exuberance, so we as her creatures also need time to pause our endless energetic endeavours and receive the gift of rest so we will be revived for the next season of growth, life and development. It’s as if that last blaze of fiery colour in autumn, when the Earth’s energy seems like it is burning up, is a metaphorical message that when we burn out, we too need a period of inactivity to recover.

I’ve been thinking for some time about the different types of burnout and how to recover from these, so now seems the perfect time to write about it. I apologise I’ve been so busy working on my historical fiction novel WIP – I had agreed with a fellow novelist to exchange completed first drafts by the end of the year, so have been striving to make that deadline – I’ve had little time for anything else, including this blog. But having had my energy, enthusiasm and inspiration sabotaged by a recent flu brought on by physical, mental, emotional and spiritual exhaustion, I now feel I need to write it as much for myself as for others!

So I hope something in the below will be of use to you, too – and that wherever you may be in your own journey(s), you will receive the gift of rest this season offers.

What is burnout?

Burnout is defined as ‘a state of mental, physical, emotional and spiritual exhaustion caused by prolonged and extreme stress’. It occurs when we feel overwhelmed, drained, and no longer able to cope with the demands and pressures of life.

While the symptoms of exhaustion, feeling overwhelmed and drained could also describe other conditions such as depression, anxiety, isolation or grief, burnout is a unique phenomenon that requires a very different recovery strategy. What makes burnout different is that the term itself implies something that was once on fire – eg fired up with enthusiasm or aflame with passion, for example, by commitment to a cause or belief – is now extinguished.

Seen through this lens – as in, the extinguishing of a former enthusiasm or passion caused by prolonged exposure to extreme stress – the term and treatment for burnout can be understood and applied to many variations of the condition: from compassion and activist fatigue to writer’s and artist’s blocks to professional burnout from overwork; to the relentless pressures of perfectionism and productivity; to the cumulative toll on our psyches from consuming an endless stream of horrifying news media, such as we’ve had recently with the wars in Ukraine and Gaza; and just the sheer exhaustion of coping with everyday pressures that zap our energy and joy in living.

In the below, I examine each one of these and suggest remedies for overcoming them.

Activist fatigue

By token of its very name, activism implies action – it is defined as ‘the policy or action of using vigorous campaigning to bring about social or political change’. It is also described as ‘the policy or practice of doing things with decision and energy’.

Types of activism include campaigning via protests, demonstrations (marching, public sit-ins, strikes, etc), boycotts, rallies, events and petitions via media/social media for: human rights (eg of prisoners, refugees, disabled persons, homeless, victims of war and oppression, etc); the environment (eg raising awareness of climate change or specific impacts on nature, such as pollution, tree felling and destruction of habitats, ecosystem collapse or biodiversity threats); animal rights (eg cessation of laboratory testing on animals, fairer treatment and conditions for farmed and/or circus animals, cruel caging, exploitation or poaching of animals, protection of rare or critically endangered species); and political or religious causes and platforms (eg through advocating for reform via democratic actions such as voting, organising unions or even agitating for open revolt against systems seen as unjust).

Activists tend to be passionate idealists. They expend great personal energy in the hopes of bringing about change. While it is true that sustained, collective campaigning can and does bring about much-needed societal change or reform, it is not without personal costs and challenges. For example: 1) becoming so excessively single-issue-focused – on one particular message or campaign issue – that you become blind to all other issues, including self-care and vital relationships; 2) feeling alone in a cause, thereby becoming isolated, defensive and/or resistant to others’ perspectives; 3) other impacts, such as imprisonment for anti-social or extreme behaviour; and lastly (4), what began as an idealism-empowered energy can run out and eventually crack through sustained resistance or wearing down of energies, such that the initial idealism is replaced by a pervasive cynicism and negativity.

So, how can you guard against activism fatigue?

First, it’s important to avoid single- or narrow-focused extremes – as psychotherapist Dwight Turner says, ‘It’s important we nurture the other parts of us that aren’t activists: the partner, the parent, the gardener, the friend down the pub on a Friday night’. It’s essential to maintain a balanced life in the midst of activist endeavours. Practice doing daily self check-ins to see where you might be out of balance or need to give some attention to your own self-care and other vital relationships that help you stay sane and healthy.

Second, watch out for ‘presenteeism’ – feeling like you must be present and actively involved at all times or the cause will suffer. If you find yourself thinking you must be there or you’ll let the side/cause down, you need to remember you are not God – you alone cannot save or change a situation, and burning yourself out trying to do so is only going to harm both you and discredit the cause. Besides, chances are that by standing aside, others may be motivated to join the battle.

Third, activism often provokes very intense, and occasionally very negative responses – including the negative press and reactions of UK and other governments that have taken steps to eradicate the disruption caused by climate protestors through the Public Order Act 2023 – and you may end up feeling alienated, isolated or rejected by those who do not empathise with the cause or whose ideas or solutions may clash with yours. It is bad enough to suffer negative media portrayal and fears of arrest or imprisonment for the cause, but not feeling sufficiently understood, appreciated or vindicated, even by those who should care for you, or who supposedly fight alongside you, can also take a very heavy toll. For this, you need to find a trusted friend who can offer a neutral, objective perspective and who will support you in maintaining self-care regimes.

Lastly, sustained vigorous campaigning in the midst of this can sometimes result in an inevitable sense of cynicism and despair. Some activists will eventually become so overwhelmed helpless and jaded they can reach a point of no longer caring about anything. If you find your activism has drained you this much, step away from your campaigns and practise other life-affirming pursuits until you feel able to engage again – but ensure you maintain a balance to avoid burnout.

Writer’s and artist’s blocks

Why have I listed creative or writer’s blocks in an article on overcoming burnout? This is because I believe we can easily become blocked as writers and other creativity practitioners through many of the same underlying characteristics of perfectionism, productivity obsession, comparing ourselves with others, lack of self-care/self-belief/self-value, and obsessive over- or mono focus that tend to promote the other types of burnout listed here.

Webster’s dictionary defines writer’s block as ‘a psychological inhibition preventing a writer [insert artist, musician, entrepreneur, poet, screenwriter, etc as applicable] from proceeding with a creative piece’. For those who earn a living through creative work, that sense of inspiration drying up and or no longer being able to create can fill you with an absolute blind panic.

The English Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge is credited with inaugurating the concept of ‘writer’s block’ (which he described as an ‘indefinite indescribable terror’ of not being able to produce worthy work) in the early 19th century. Romantics believed their inspiration came from an external, magical source – eg the gods or muses – and that when they were not experiencing a flow of ideas or inspiration, the gods or muses were being capricious or not favouring them with divine succour.

Allied to this is the romantic notion that an artist must suffer for their work – that somehow the best creative work and beauty must proceed out of an artist’s inner torment. While it’s true pain and suffering can indeed spawn great creative work, this idea of the tortured artist has all too often been used as an excuse for self-destructive behaviour, substance abuse or other self-sabotaging behaviours.

But waiting for inspiration from muses to strike – or believing you must somehow suffer before you can truly create – is a surefire way to sabotage your creative work and self-belief as a creator. Being an artist is about doing the work, regardless of how you feel. It is ‘1% inspiration and 99% perspiration’ – so the daily act of ‘showing up at the page’/canvas/screen/instrument is the best way to maintain a vital creative practice.

But what else can we do to overcome those times we hit a wall and feel we cannot move on? When no matter how hard we try, the words or images simply do not come? When we feel completely burned out and have lost our creative mojo?

1. Don’t beat yourself up with thoughts or self-talk of being a failure. You are NOT a failure simply because you have a few days – or even weeks or months – when you feel stuck or simply cannot get into a flow. Eventually, if you keep showing up at the work, you will come out of your rut in time – ‘This too shall pass.’

2. Take a break. Sometimes the solution to something you are striving over will come as you allow your mind to relax. Go for a walk, get some exercise, take a bath, travel or do some necessary chores. This is not the same as procrastinating, because our minds are still working on the solution to a problem even when we have objectively switched off. Even unconsciously thinking about creative work is essential to producing it – it is part of the cognitive process.

3. ‘A change is as good as a rest’. Try doing a different type of creative work – for example, doodling, drawing, freewriting, writing haikus, wordplay games, playing an instrument, dancing, listening to music, collaging or any other art form that involves a playful, free-association type of approach – or perhaps try a different approach than you normally use (for example, if you are a pantser, try plotting; if a plotter, try pantsing).

4. Talk about it with a trusted friend or fellow writer – usually they’ve also been there at some point and may have suggestions that will encourage you. Knowing you are not alone in your struggles helps.

5. Imagine you are talking to someone else who is suffering from the same problem. Then try writing down everything you say – perhaps that will turn into a first draft.

6. Move around. As anyone who has suffered from insomnia will tell you, just forcing yourself to sit in front of a blank page doesn’t always do it. Sometimes the best thing to do is get up and move around. Or perhaps try tackling tasks you’ve been putting off for a while, like clearing your desk, organising files, or doing a spring-clean or declutter.

7. Work on a different section. There is no law that says you must always work in a linear fashion. If you feel clear about another scene or the ending, write that and come back to the section you were on later. Sometimes writing out of sequence will help you understand what you need to do with the section you are struggling with.

8. Change locations – try writing or painting in a different space, or perhaps a café, park bench or local library. There may be something in that new environment – a snatch of conversation, a particular smell or startling image – that will inspire you.

9. Read a book or look at paintings by favourite creators that inspire you. Regular reading and study of other authors’ and artists’ works will help rejig your own creative juices, teach you more about the craft, and perhaps motivate you to find and refine your own voice or style of working. It will also provide a much-needed escape, enabling you to travel to other locations and see things through other characters’ eyes – think of it as a vacation from your own voice and perspective.

10. Change your tools – for example, if you always write onscreen, try writing by hand. Perhaps use a writing app like Scrivener. If you always work manually in black pen or pencil, try painting using colour, or perhaps try a painting software tool like Procreate.

11. Retell your story using a different genre or style – for example, try using a basic fairy-tale ‘Once upon a time’ structure if you become stuck on plot or structural issues. Sometimes reducing the plot lines to this simpler format will clarify the bigger picture of what the story is actually about.

12. Step back and listen to gain objectivity about your work. If you feel a passage isn’t working, use the ‘Read Aloud’ function in Word to listen to how it sounds. Hearing your work read or reading it aloud is a crucial part of the editing and revision process, and can also help you see what needs attention when you get stuck.

13. Ask your characters questions about what they want, and how they are seeing or feeling in the situation(s) you are describing, and then listen to their responses.

14. Finish now – edit later. If perfectionism is holding you up, remind yourself that before you can begin the editing and revision process, you need to complete your first draft – you can’t edit words or scenes that only exist in your head! Many writers call it a ‘vomit draft’ for good reason – so don’t worry about perfecting it now. Just get the words down and commit to editing, honing and revising later.

15. Try prayer and meditation – perhaps combined with yoga and/or breathing practices. Becoming still, listening and being mindful of sensory stimuli around you will help you calm and declutter your mind, making you more receptive to fresh ideas and inspirations.

Compassion fatigue

Although it is similar to activism fatigue, compassion fatigue affects those mostly involved in the helping professions – eg nursing, teaching and/or ministry. Such persons usually begin with a genuine desire to help others less fortunate than themselves, but ultimately by engaging in self-sacrificial behaviours and putting others’ needs first to the detriment of their own, they reach a point of personal exhaustion and extreme burnout, making them unable to help or care for others.

Some years ago, I recall being challenged by a tendency to displace my own needs by caring too much for others through a book my sister sent me called ‘Women Who Love Too Much’ by relationship therapist Robin Norwood. Although this book focuses on women who become involved with unhealthy or destructive relationships in a desperate and vicious cycle of lack of self-worth and self-care, I began to see how much these principles extended to my then-involvement with Christian ministry. While the Bible says, ‘greater love hath no man (woman) than this, that he (she) lay down their life for their friends’ (John 15:3), it also says, ‘Love others as you love yourself’ (Matthew 22:39) – because in truth you cannot practically or authentically love others if you fail to love and take care of yourself.

While self-sacrificial attitudes and actions are commendably noble, they can all too easily stem from misplaced motives such as pride or an unhealthy messiah or saviour complex, or again from a woeful lack of self-worth and self-care. The phrase, ‘physician, heal thyself’ (Luke 4:23) is valid in that just as a physician who is himself/herself ill cannot heal others, so too someone who does not take time to minister to themselves will be effectively unable to minister to others. You cannot give to others when your own well has run dry!

When you find your inner well of compassion and concern for others has dried up, that is your body and spirit saying you need to begin applying self-care – for example, take time out to do things you enjoy and that build you up. Learn to listen to your body by resting, eating, sleeping and exercising when you need to. You actually need to become ‘selfish’ in caring for yourself appropriately before you become selfish in other, more harmful ways – eg self-centred, self-righteous, self-justifying, self-pitying or self-destructive.

There is a reason why God instituted the Sabbath as a rule for humans – that is because, as mentioned previously, all living systems need an enforced period of rest. As a creature of this Earth, you are not exempt from its patterns and cycles – you cannot simply go on and on and on without time out to rest. Jesus said, ‘Come to me all who labour and travail and are heavy-laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke and learn from me, for I am gentle and lowly of heart. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light’ (Matthew 11:28-29). In other words, those involved in ministry need to learn not to attempt to do things in their own strength, as a point of pride and self-reliance, but to do them in His strength.

Some basic tips to help you recover from compassion fatigue are:

1) practise mindfulness – become aware of your thoughts, feelings and physical sensations; 2) focus on your breathing, and attempt to slow it down when you become anxious or worried;

3) consider small things you can still control or change whenever you feel overwhelmed or out of control, such as your immediate work environment;

4) establish a good self-care routine such as eating, sleeping and exercising appropriately and at regular times;

5) reach out to others – family, friends, a peer group or professionals – for support;

6) set aside time for meaningful personal hobbies and activities, and to connect with loved ones;

7) take a break from news and limit the amount of time you spend online and on social media every day.

News and social media burnout

Media consumption – news, and particularly social media – has become such a part of our daily lives that we often don’t realise how much cumulative anxiety and stress our psyches, minds and bodies are subjected to through constant exposure to it. And if we consider burnout as prolonged exposure to extreme stress, it is all too easy to see how daily news consumption – even if it seems like harmless, mindless scrolling – can contribute to overall sensations of burnout and affect one’s ability to cope with the pressures of daily life.

Repeatedly digesting negative news headlines has been show in studies to affect mental and physical health through news-related stress and media saturation overload. Watching traumatic news clips of bombs exploding in a city or seeing victims shaken by war, mass violence, natural disasters or civil disruption will cause various physiological responses – your heart rate quickens; you blink rapidly; your skin pricks; your mood darkens; and your ability to make decisions or perceptual distinctions is affected.

‘They may just have read about an animal on the verge of extinction or the latest update on polar ice caps melting… [and while] they may not even recognise at first that the news has affected their mood, they’re perserverating [sic] on it – it’s bothering them.’

—Don Grant, PhD, of the American Psychological Association (APA),

Further, the fact people often use marketing strategies on social media – often enhanced artificially by Photoshop or AI – to convey or project images of perfection and success can create feelings of failure, unhappiness and distress in viewers who compare their own lives or looks with these images. Social media contributes to personal unrest and a crippling perfectionism by creating a sense of ‘FOMO’ (fear of missing out) and lack, driving efforts to compensate by overdoing activities and striving to ‘keep up with Joneses’.

Psychologists are coining new terms to describe conditions derived from news and media consumption: ‘media saturation overload’, ‘headline anxiety’, ‘doomscrolling’, ‘headline stress disorder’, media post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and social media burnout (SMB). Since many people get their news from social media (more than half of US adults, according to a 2020 Pew Research survey), the trend for driving clicks through negative ‘clickbait’ messaging contributes to feelings of overwhelm, hopelessness and powerlessness to overcome or bring about positive change.

If you find your level of media consumption makes you constantly stressed, angry, resentful, depressed or burned out – for example, you experience symptoms such as body tension, over-reliance on drugs or alcohol, a rise in pulse rate, anxious or obsessive thoughts and worries impacting your sleep and normal function, lack of joy and interest in life or normal social activities – you need to insert some media guardrails.

Try the following:

1. Turn off all phone notifications.

2. Add tech-free periods to each day.

3. Limit your news consumption and social media check-ins to only 15 minutes per day – set a timer to ensure you stick to it.

4. Don’t bring phones to the dinner table.

5. Talk to people while waiting in line rather than checking your phone.

6. Journal or write about your responses to the news as a method of processing.

7. Take action – sign a petition, donate, or get involved in a charity or community response to a problem. Doing something proactive is a positive way to process your emotions so that they do not lodge in your body.

Professional burnout

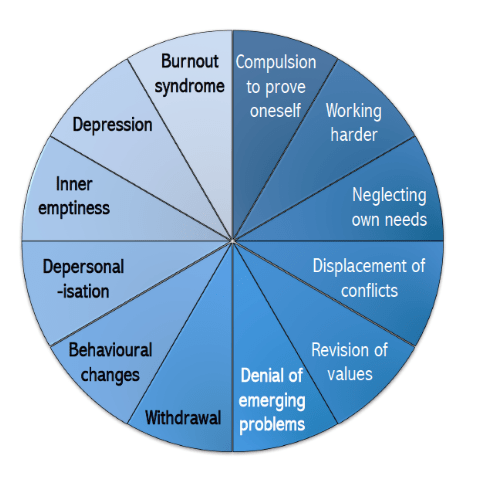

The term ‘burnout’ was first coined in the 1970s by American psychologist Herbert Freudenberger to describe the effects of chronic mental and physical fatigue in professional work. He and his colleagues usefully identified 12 stages of burnout in relation to one’s career as the following:

Stage 1. Excessive ambition – while having ambition and an enthusiastic desire to work hard and succeed is not a bad thing, the clue here is in the word ‘excessive’. What begins as a reasonable aim of progressing in your career can so easily be replaced by an inner compulsion to prove your worth to others in order to feel ‘good enough’. Answer: The moment you begin to compare yourself with others, step back and tell yourself you are already good enough and doing enough. You ARE worthy as you are!

Stage 2. Working harder and faster – If you are not careful, you soon find yourself volunteering to take on extra responsibilities and tasks, and then find your pressure accelerating beyond your normal human limitations as you strive to work harder and faster. Soon, the pressure of work begins to bleed into your personal life, and you find it harder and harder to switch off or compartmentalise. Answer: In the same way your computer will eventually crash if you have too many tabs open, once you find this blurring of boundaries between life and work happening, you literally need to switch off entirely and then restart yourself by resuming activities ONE TAB AT A TIME.

Stage 3. Neglecting your physical and emotional needs – By this stage, your priorities have shifted to placing others’ needs and demands first. As a result, you are typically omitting to look after your own needs. You may begin to skip meals or sleep erratically, fail to take time out to stretch, exercise, meditate or do proper breathing exercises, and neglect communicating and connecting with family and friends. As a result, your health and emotions suffer – you gain weight; experience insomnia; have frequent back and neck pain or other health issues; your attention wanders, making it harder to focus; and you become quarrelsome or easily provoked, which then damages your relationships further. Answer: BEFORE you sit down to work, make sure you eat a proper meal and do some morning stretches, journalling and/or meditation; schedule breaks throughout the day to stretch, breathe and go for a brisk walk; and make time every 2–3 days to schedule calls and chats with loved ones.

Stage 4: Displacing problems – When you are too focused on work, you also tend to ignore other issues and problems, including a niggling sense of things not being right. But suppressing these problems will not make them go away; you’ll just end up feeling jittery and prone to overreact to minor setbacks or perceived personal slights, which may make you overly defensive or critical. Answer: Rather than looking for someone or something to blame, schedule a DAILY CHECK-IN with yourself – either through journalling or a brief prayer or meditation – to monitor your bad habits and self-excuses. Keep a daily to-do list to help you stay on top of the little things (‘Catch the little foxes that spoil the vineyard’).

Stage 5: Revision of values – Once displacement begins to happen, it becomes all too easy to drift away from your core values and raison d’etre. Everything that gives your life meaning and purpose – friends, family, hobbies – gets sacrificed on the altar of work and your entire sense of self-worth becomes dominated by your desire to be productive and meet deadlines or achieve work goals. Answer: Work is only one part of your life – you need other things to give meaning and dimension to your life. Just as you need to eat a balanced and varied diet for physical health, so your whole being needs balance to function properly. Begin by scheduling time to reward yourself each day with a half-hour spent doing SOMETHING OTHER THAN WORK.

Stage 6: Denial of new problems – When your focus is out of balance, so too is your perceptions of others. You begin to see others as lazy or demanding, and become intolerant, unsympathetic and cynical in your attitudes towards them. Rather than seeing how much you’ve changed to become rigid and inflexible, you blame work pressures or lack of time. Answer: Here’s how failing to check in with yourself will manifest in your behaviour, which you don’t even recognise as a problem. If you’ve become blind to your shift in attitudes, you need others to hold up a mirror to you. Although it might be hard to accept criticism, ASK OTHERS if you seem different and how they think you’ve changed.

Stage 7: Withdrawal – By exclusively focusing on work, you automatically withdraw from social engagements and relationships, becoming isolated and secluded in the process, with a non-existent social life. You might not even remember the last time you had a conversation that didn’t revolve around work. The temptation here is to escape through guilty pleasures such as bingeing on drink or food, which often has a catch-22 effect of piling on shame that makes you withdraw even further. Answer: No matter how isolated you’ve become, it is essential to break out of this rut as soon as possible. Phone a friend or relative, or REACH OUT to an anonymous agency such as the Samaritans. Ask them to change the subject every time you talk about work.

Stage 8: Impact on others – Your exclusively work-focused isolation and burnout begins to have an impact on and be noticed by others. Perhaps you are always tired and irritable, your moods are erratic and unpredictable, or you do things like miss a doctor’s appointment or important meeting, or forget to pick your kids up from daycare. Answer: It’s important to BE ACCOUNTABLE to someone. If you don’t live with someone or have a friend or family member who will check in with you regularly and hold you accountable, you may need to seek external help with a professional therapist or group.

Stage 9: Depersonalisation – At this stage, you start to feel detached from everything and everyone, including yourself. You begin to feel hollow and as if you are outside your own body, merely watching yourself going through the motions of life but without any connection to your activities. Where you once felt passion, enthusiasm and motivation, you now feel indifferent to your work or unconcerned by any problems in it. At this stage, your personal investment or ability to care is drained out of you. Answer: When you begin to feel disconnected from your own personal commitments or involvement, you need to OWN THEM again by consciously using ‘I’ (I/me/my/mine) pronouns.

Stage 10: Inner emptiness/lack of worth and meaning – Your overfocus on work has robbed you of any sense of fulfilment or meaning in life. You begin to question your value and feel as if all your efforts are in vain. You begin to fantasise about quitting, moving on or leaving your career. Answer: Rather than running away or depending on external stimulants of food or alcohol to fill that sense of emptiness or further numb your hollow feelings, you need to begin to BECOME MINDFUL – take a moment to step back and recognise your patterns, then make small, incremental changes to your daily habits.

Stage 11: Depression/Existential crisis – Everything now seems a blur and has lost all sense of colour and life. You are mentally and emotionally exhausted and feel lost and uncertain of anything. Rather than being focused, you simply drift in a haze where everything seems meaningless, absurb or pointless. Answer: At this stage you likely require EXTERNAL HELP such as therapy or medication such as antidepressants. Seek help from a GP and take any medication or supplements as directed.

Stage 12: Full burnout syndrome – If you have reached this stage, you are now at breaking point, and likely to experience a full mental and/or physical breakdown. At this stage you will need extended time off from work to recover, as well as medical attention. Answer: When you have reached the end of your mental and physical limitations, there is nothing more you can do but TAKE TIME OFF and completely cease all work activities until you recover. It’s important to take as much time as you need and not try to rush this stage until you are completely healed.

Conclusion

I hope you will find some of these tactics helpful, wherever you are in your personal journey or on the stress-o-meter scales of life. As God knows the pace of modern life is only likely to increase, the varied stresses we all face are also likely to proliferate. But returning to the seasonal theme, the most important thing to recognise is that you are not a machine – you are a part of nature. And just like nature needs to rest, so do you (and I). I pray we will all take time out this winter – and regularly throughout the year – to receive the gift of rest.

Pic credits – from top (main image) to bottom: Cover image: Resting male/man, GLady (Pixabay); 1) moritz320 (Pixabay); 2) Kevin Snyman (Pixabay); 3) Adrian Fisk, on chinadialogue.net; 4) lukasbieri (Pixabay); 5) painting of Samuel Taylor Coleridge by Peter Vandyke, 1795 (Wikipedia); 6) modovisibile (Pixabay); 7) geralt (Pixabay); 8) Dalai Lama quote, www.habitsforwellbeing.com; 9) Kamran Aydinov (Freepik); 10) Herbert Freudenberger (Wikipedia); silviarita (Pixabay).

Slideshow: 1) Winter, Kyoto, Japan, Darkness_S (Pixabay); 2) Jay Bird Branch, Tomas Proszek (Pixabay); 3) Relaxing, Lounging, Saturday Jill Wellington (Pixabay); 4) Ducks, Ditch Side, Cold, Elsemargriet (Pixabay); 5) Hedgehog Fall Hibernation, Terranaut/Peter Schmidt (Pixabay)

One thought on “THE GIFT OF REST”