This short story was first published in 1991 in Wilderness Tips, a collection of 10 of Margaret Atwood’s short stories; I found it in a 1992 compilation, Caught in a Story: Contemporary Fairytales and Fables, and have always remembered it as one of the most powerful, resonant and truly incandescent stories I have ever read.

The story’s title refers to the title of what is described as ‘a series of short, connected lyrics’ read by a mysterious, gifted poetess known as Selena – likely modelled on real-life Canadian novelist and poetess Gwendolyn MacEwen (pictured; credit John Reeves / Library and Archives Canada / PA-195871) – in a café called ‘The Bohemian Embassy’ in Toronto in 1960: a time when

“Poetry was the way out then, for young people who wanted some exit from the lumpen bourgeoisie and the shackles of respectable wage-earning. It was what painting had been at the turn of the century”.

This, along with a few other descriptions of the area (“small vertical houses” with “peeling woodwork” and “sagging porches” – note the rule of three used here; it is also used in the repeated zero decades the main character encounters Selena (1960, 1970, 1980) – define the physical and emotional landscape of the story as “the sort of constipated middle-class white-bread ghetto he’d fled as soon as he could, because of the dingy and limited versions of himself it had offered him”.

Through these few brief acerbic descriptions at the beginning, Atwood establishes the era’s particular zeitgeist: the sense of being trapped and creatively stifled by suburban middle-class North America. This is a time and landscape anyone who grew up as a bohemian-inclined artist or poet in the crassness of 60s/70s North American suburban non-culture, as I did, will immediately relate to; its cri de coeur to escape these materialist shackles as soon as possible is a main reason this story has always resonated with me.

Those around at that time may also recognise the story’s thematic similarity to the mournful lyrics of another stellar and influential Canadian (Joni Mitchell) in “The Last Time I Saw Richard”: “all romantics meet the same fate, someday – cynical and drunk and boring someone in some dark café”. I do wonder if Atwood named her character with this song in mind. This landscape is so rife with perils of soul artistic destruction, one must escape it somehow or remain trapped forever, strangled by its soul-destroying, artificial tinsel.

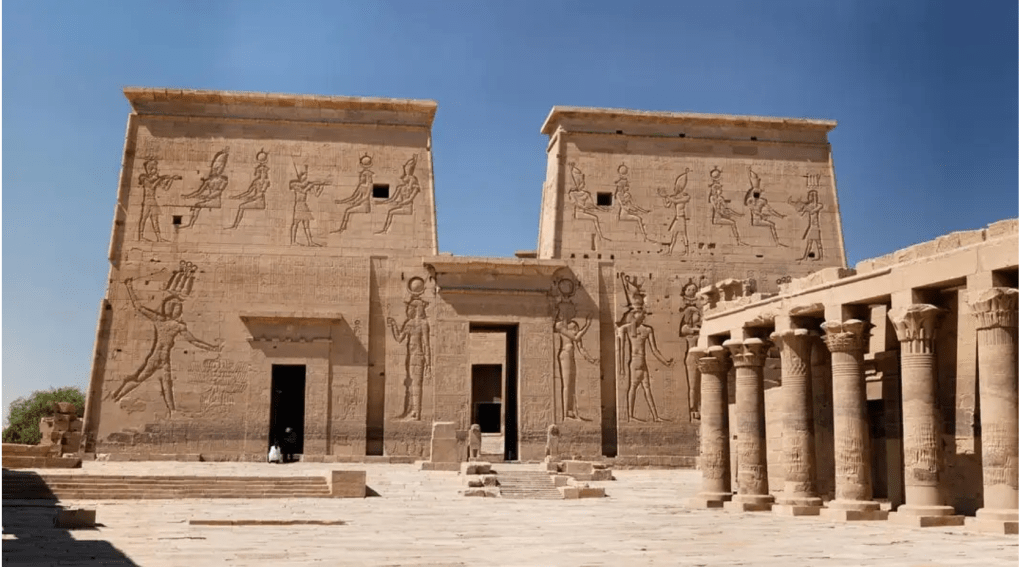

Yet the actual era and location specifics are irrelevant to the true meaning and power of the story, since a romantic longing for the ‘other’ or ‘beyond’ is engrained in the human psyche since time immemorial. It is this psychic universality, as well as its reference to ancient Egyptian mythology, that justifies its inclusion in a compilation of fairytales and fables. But beyond this, and of particular relevance to writers, the story is essentially a hymn (literally; see below) to the power of poetry, of story, to transmogrify our otherwise meaningless human existence by lifting it to the realms of the sublime.

Echoes of otherworldliness

While the where, when and what are established early on in the story, it actually begins with the who: an otherworldly young woman named Selena, whom the main character – a wannabe/failed but somewhat pretentious poet and academic named Richard – is trying to imagine where she came from:

“How did Selena get here? This is a question Richard is in the habit of asking himself, as he sits at his desk again, shuffling his deck of filing cards, trying again to begin. In a way, it’s the main question: because she was then, and remains, altogether improbably, an anomaly for her time and place. Or as the new physics would say: a singularity.”

The fact the story begins with a question, then tells you straight away that this is the main question, underlines the peculiar otherworldliness of the poetess as not really belonging to any particular time or place. It also uses small, telling details to reveal the character and his quest immediately; we know Richard is determined to unravel and understand Selena’s origins, as if by doing so he will finally possess her – in much the same way the poem Isis in Darkness is about the goddess Isis trying to piece together her lover, the god Osiris’s, broken body as an act of love. We also know he is in the habit of failed attempts: “trying again to begin”.

Richard’s obsessive quest is driven by his own need to recover a sense of wholeness in himself, but here it is demonstrated (shown, not told) by the simple image of him shuffling a deck of filing cards: a deck (whole) broken into separate components. That they are filing cards shows he is trying to organise or systematise something he does not understand, but is determined to find answers for. The act of shuffling simultaneously indicates frequent repetition (we sense he does this regularly) and randomness (the outcome is unknowable, filled with infinite possibilities, any of which could be accurate).

The reference to physics is not accidental; it carries with it an inherent echo of the second law of thermodynamics, in which all systems are subject to decay (eg loss, breakdown, unwholeness); this also pops up in the lyrics of a song, later quoted by Selena: “Change and decay in all around I see/I’m not prepared for eternity.” Further, the meaning of a singularity – according to Einstein’s 1915 Theory of Relativity, which describes it as “the centre of a black hole, a point of infinite density and gravity within which no object inside can ever escape, not even light” – is relevant to the story’s central concept of an artist being trapped in the twin black holes of suburbia and academia, and the goddess Isis being in a realm of darkness. The physics reference also reveals a key element of Richard’s nature: he is scientifically oriented, with a need to understand a mysterious universe through a system, eg physics and cataloguing with index cards.

After beginning with a series of imaginative speculations about Selena’s origins (“he sees her landing froma transparent spacecraft, a time-warp traveller en route from Venus or Pluto”), in the next section, broken by a line space, the narrator tells us blankly:

“A factual account exists. She came from the same sort of area that Richard came from himself: old Depression-era Toronto.”

The story continues in this vein, juxtaposing the everyday, prosaic, factual/scientifically verifiable aspects of Richard’s life and the tawdry realities of Selena’s real-life existence with a much grander vision of something other, something beyond, something that cannot be defined or reduced to mere equations on a blackboard.

Isis and Eros, belief and unbelief

We are also told early on that at the time Richard meets Selena, he was “slogging through” the existential classic Being and Nothingness. He is already “feeling jaded, over-the-hill” at 22; a romantic-turned-cynic. He is presented as someone who strives to balance the metaphysical and impenetrably unknowable with facts, figures, knowable and countable verities – someone who has no belief in God, but a desperate need, somewhere in the corner of his soul that remains alive, to believe in something above or beyond himself.

When he first encounters Selena, Richard is mesmerised by the seductive power of her voice as she reads “Isis in Darkness” at the café. He is transported by the strange, otherworldly location in ancient Egypt and the rich world of imagination her lyrics evoke. He is immediately persuaded Selena is the real deal as a poet, and that all his own poetic efforts are worthless by comparison:

“He went back to his rented room and composed a sestina to her. It was a dismal effort; it captured nothing about her. He did what he had never done before to one of his poems. He burnt it.”

Yet Richard’s obsessive desire for Selena is confusing both to him and others, who interpret it as physical lust. Another non-accidental reference is the fact he toys endlessly with the order of the words ‘spiritual’ and ‘carnality’ in the title of his major academic opus (‘Spiritual Carnality: Marvell and Vaughan and the 17th Century’). Yet any carnal desire to quench his obsession with Selena is never consummated, as the one time he visits her home on a nearby island, she tells him plainly, “We can’t be lovers”. When Richard asks why, she says:

“You would get used up… then you wouldn’t be there, later… when I need you.”

Even though Richard desperately wants to be utterly consumed (or “used up”) by Selena and obsesses about her over a period of a few decades, in some part of his mind, he is aware he doesn’t objectively fancy the actual physical woman, who despite her brilliance and brief fame as a poet, has real-life needs and problems like any other woman.

This is seen in a scene where Selena turns up unexpectedly at Richard’s house, wearing a bruise and carrying a suitcase, in need of somewhere safe to stay. It is the catalyst for an end to Richard’s prosaic, middle-class marriage, as his cheating wife Mary Jo expresses her disgust at his “letching after” a woman she sees as a “weird flake” because of her cheap, charity shop clothing (Selena is described in the opening scene as wearing a tablecloth with images of dragonflies on it as a shawl).

Eventually Richard acknowledges this discrepancy between a physical desire for Selena and what it is he really craves:

“It was not lust. Lust was what you felt for Marilyn Monroe, or sometimes for the strippers at the Victory Burlesque (Selena had a poem about the Victory Burlesque. The strippers, for her, were not a bunch of fat sluts with jiggling, dimpled flesh. They were diaphanous; they were surreal butterflies, emerging from cocoons of light; they were splendid). What he craved was not her body, as such. He wanted to be transformed by her, into someone he was not.”

Darkness and light

For all Selena’s human flaws, vulnerabilities and inevitable decline as a literary sensation – as revealed over a few decades until her untimely death – and for all his outward world-weary cynicism, low points and writerly/academic despond, Richard persists in cherishing a vision of Selena that remains untarnished with mortality. The unbelieving scientist has become a worshipper, an idolater; he has apotheosised the woman he can never own into a goddess. For him, Selena will always exist as an earthly embodiment of Isis, whose wandering in the darkness, seeking to gather the fragmented body of Osiris, emanates divine illumination.

After her death, Richard concludes that although he will never match her literary brilliance, he can at least share in her reflected glory through the act of homage in chronicling her life. As he picks up the mosaic-like fragments of her life, he, too, will become like Isis, magically gathering strength and becoming whole in the darkness:

“Isis in Darkness, he writes. The Genesis. It exalts him simply to form the words. He will exist for her at last, he will be created by her, he will have a place in her mythology after all. It will not be what he once wanted: not Osiris, not a blue-eyed god with burning wings. His are humbler metaphors. He will only be an archaeologist [note scientific reference]; not part of the main story, but the one who stumbles upon it afterwards, making his way for his own obscure and battered reasons through the jungle, over the mountains, across the desert [note rule of three again], until he discovers at last the pillaged and abandoned temple. In the ruined sanctuary, in the moonlight, he will find the Queen of Heaven and Earth and the Underworld lying in shattered white marble on the floor. He is the one who will sift through the rubble, groping for the shape of the past. He is the one who will say it has meaning. That too is a calling, that can also be a fate [note conscious shift to words related to faith / belief here].”

This passage describes a physical movement across an internal, imaginary landscape of threes towards his ultimate goal of divine transmogrification. It encapsulates the main themes and character arcs of the story: Richard progresses from smug, cynical, self-congratulating dilettante to humble, believing, artistic worshipper; from early scientific leanings to finding his true calling as an ‘archaeologist’. He finds an ultimate redemption of his own brokenness and literary failings through his concluding rule-of-three actions:

“summoning up whatever is left of his knowledge and skill, kneeling beside her in the darkness, fitting her broken pieces back together.”

The final reference to light (knowledge) in the midst of darkness leaves the reader lingering with him in the place of shadows, tasting with Richard the full bittersweet remorse of sacrificing one’s own art to a shadow occupation (in his case, as a literary academic).

For me, this story has always served as a powerful fable about avoiding this same fate as an artist, which I believe was Atwood’s didactic intention in writing it.